Just a few days before the election, I predicted that Labour would win 270 seats and the Conservatives 275, and Labour would form a minority government. I begin with this confession as a warning that the wise should read what follows with scepticism (to say the least). Myself, along with many other “experts” got it wrong, totally wrong.

In my experience electoral post-mortems tend to derive from pre-election ideologies, rarely generating new insights. If it comes at all, new thinking arrives much later. In any case, having done a real howler in my prediction of the outcome, I shall avoid compounding the analytical felony by off-the-cuff diagnosis of Labour’s failings. Instead I speculate what will be the economic consequences of the decisive Tory win.

The Conservative Party’s campaign pronouncements and continuation of Cameron in No 10 and Osborne in No 11 Downing Street make it easy to anticipate the coming economic policies in England. These can be organised into macroeconomic and public finance (expenditure and taxation).

At the macroeconomic level George Osborne will continue with expenditure reductions in search of an overall fiscal surplus (with a smaller state the sub-text). By itself this will continue the growth-depressing effect that during the past five years resulted in stagnation, then a very protracted and sluggish recovery.

The International Monetary Fund predicts that growth rates will slow in the coming year, especially for developed countries. This implies little or no external boost to the UK economy. As a result, the chancellor is unlikely to deliver his promised fiscal surplus for several years.

Should investment continue to be sluggish, household expenditure financed by borrowing will drive growth – albeit weakly. A growth rate well below the historic trend of 2.3-2.5% is likely without a strong recovery of private investment. Increases in household debt will add to other structural weaknesses, most notably the stagnation of manufacturing.

If the Tory government delivers on its tax and expenditure promises, income and wealth inequality will increase. Reduction in the upper rate for income tax will cause greater income inequality, and proposed changes in inheritance tax will continue the trend toward wealth inequities. Britain – or at least England – will be a land of deep division between rich and poor with a squeezed middle class.

Cuts in expenditure over the next five years will add to increases in inequality. As calculations from the Office of National Statistics show, reduction in public services in itself increases inequality because reliance on these is inversely related to income, even when the much-attacked “benefits” are excluded. One of the strongest inequality impacts of cuts in social expenditure are their gender impact.

North of the border

The Scottish National Party’s landslide means that Scotland has become a de facto self-governing province of the UK. Scotland joins North Ireland as a part of the country in which the so-called national parties have almost no presence. And Britain now has two regionally based economic philosophies that imply substantially different policies – neo-liberal in England and social democratic in Scotland.

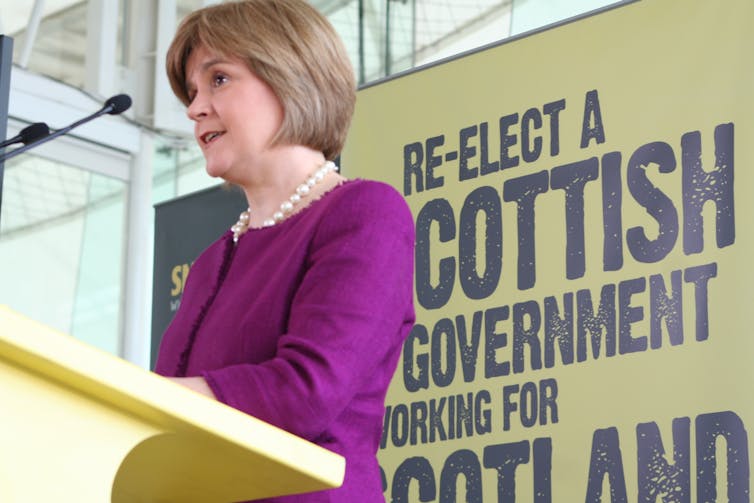

Nicola Sturgeon made the demand for greater fiscal autonomy one of the central themes of the SNP campaign. This may harden into the demand for full fiscal autonomy – the power to tax and an end to the block grant (the funding allocated to them from parliament in London).

The social democratic policies in Scotland include no prescription charges, no university fees and no bedroom tax. The first two reflect the judgement that better health and education are activities that bring benefits to all society. Overall, a social democratic country, which the UK once was, views public provision as essential to an equitable and well-functioning society.

In contrast, neo-liberal ideology, championed by Margaret Thatcher and followed in a less extreme form by Tony Blair, treats social activities such as health care as commodities of private consumption.

It is clear that coexistence of a social democratic Scotland and a neo-liberal England (plus Wales and Northern Ireland) will require considerable tolerance and flexibility by politicians both sides of the border. But the gathering tensions of the past three years do not generate reason for optimism on this front.

The election did not cause the hardening of regional divisions in the UK, but it institutionalised them in inflexible form – two governments with fundamentally different ideologies. Over the coming parliamentary term, the relationship between Scotland and England may increasingly resemble the status of Catalonia in Spain.

Two unambiguous outcomes

It is unlikely that the majority Tory government will temper its neo-liberalism due to concern about the reaction of the social democratic government north of the border. On the contrary the new government in London may start down the divisive path of limiting the role of Scottish MPs at Westminster.

Different political ideologies and different assessments of EU membership will also create serious tensions. If the Conservative government adds to these limitations on the status of MPs from Scotland we could fall prey to the famous Law of Unintended Consequences in the form of an independent Scotland and an England whose default mode is Tory rule.

Perhaps for some this consequence is not unintended.