He was public enemy number one for his attempts to stand up for injustice. He was the subversive lawyer and political reformer that for many years was in danger of being forgotten. Yet in the 250th year since his birth, Thomas Muir has made quite a comeback. He is now being touted as the father of Scottish democracy, and could yet become an icon to rival the likes of William Wallace and Keir Hardie.

Muir ended up living the kind of boy’s-own story that could inspire a Hollywood movie. He was exiled to Botany Bay for 14 years in an outrageously rigged trial in 1793. He had been prosecuted for encouraging people to read Thomas Paine, who so far as the British were concerned helped to spark both the American and French revolutions. Muir had also been instrumental in the meetings of the radicalist Society of the Friends of the People in Edinburgh, and had personally sent messages of fraternal greetings to the United Irishmen on their way to becoming a revolutionary movement.

Radicalism on the high seas

Before reaching Botany Bay, Muir escaped aboard an American commercial ship; had adventures in modern-day Canada and South America; was subject to fierce diplomatic negotiations on his status between Spain and France; and was finally deported to Spain. En route, in an action where the British Royal Navy confronted the vessel on which Muir was being held, he had his face badly damaged by canon shot and, apparently, played dead under a pile of corpses to evade becoming a British prisoner, making his way eventually to post-revolutionary France.

Muir had been notorious in the years before his trial, though not always in ways you might expect. He represented the conservative part of the Church of Scotland in its attempt to have Robert Burns’ friend, the Rev William McGill, arraigned for heresy over a pamphlet the minister had written that was somewhat ambiguous over the divinity of Christ. Muir had also voluntarily excluded himself from the University of Glasgow after having questioned the financial management.

He instead entered Edinburgh University to study law, and provided free legal advice to the poor of the city. He was driven by his Calvinist as well as his political beliefs and these coalesced following the French Revolution, when the word “democracy” was mouthed by those in authority with a similar distaste to the way in which “radicalisation” is employed today. By the end of his life in 1799 at the age of just 33, Muir wanted Britain invaded by France, and to be divided into three republics: England, Ireland and Scotland. Unable to return home, he died alone in the French village of Chantilly in the last days of that January.

The Muir memory

For many years, he was not well remembered. He was one of the political “martyrs” of the 1790s commemorated on an obelisk on Calton Hill in Edinburgh in 1844, but his notoriety did not live on in folklore. Unlike other popular heroes, surprisingly few songs were written about him – an exception being “Thomas Muir of Huntershill” by folk singer Adam MacNaughton a couple of decades back (as sung by Dick Gaughan in this excerpt).

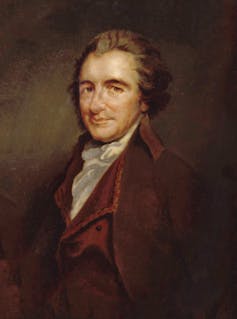

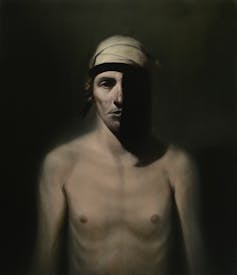

But Muir’s star has been rising lately, partly thanks to a growing organisation called The Friends of Thomas Muir. To mark the 250th anniversary of his birth, this year has seen a speech by former first minister of Scotland, Alex Salmond; a “retrial” of Muir, featuring the historian Sir Tom Devine and the advocate Donald Findlay; a new painting by Ken Currie; and even a T-shirt that sees Muir placed in a canon of similar T-shirts alongside Scotland’s national bard and Che Guevara.

These developments have received cross-party political support, but it increasingly looks as though the political ownership of Muir is being contested by the far left and the Scottish National Party. This is slightly strange to anyone of historical sensitivity since Muir had no access really to socialism or nationalism in their modern senses.

The Paris attacks help shed light on Muir for what he was not as much as what he was. He was not a revolutionary in the mould of the Islamic State, even if he was partly driven by his religious beliefs. The fact that he could support the United Irishmen, whose ranks included Catholics and Presbyterians, show that he was no theological fanatic. Instead Muir would have admired the hacker group Anonymous’ promotion of the power of the people, unsubverted and unafraid to disagree among themselves. “This is how we do things, so this is the right way” is a common sense attitude, but not much of a prospect for progress. Like Jeremy Corbyn, Muir was always unafraid to speak out against the consensus, even when at a time like these Paris attacks, the pressure is greatest to fall into line.

In essence, Muir stands for a very positive version of humanity in our enduringly selfish culture. There is an uneasy divide between this year’s celebration of his contribution to democracy and the squabble to appropriate his legacy. Democracy, after all, is about how different people can be rather than how much they form part of a tribe. In these tense times, both in Scotland and further afield, we would do well to keep that in mind.

A commemorative concert to Thomas Muir featuring Dick Gaughan is being held at the University of Glasgow on November 20.