Now is not exactly the happiest time to be a Liberal Democrat. The voters that the party lost between 2010 and 2012 do not appear to be coming back: indeed, more have left since then.

As Rob Hutton notes of party leader Nick Clegg: a public apology on tuition fees, a weekly phone-in show and being rude about David Cameron and Boris Johnson have done little to change the public mood toward him and his party.

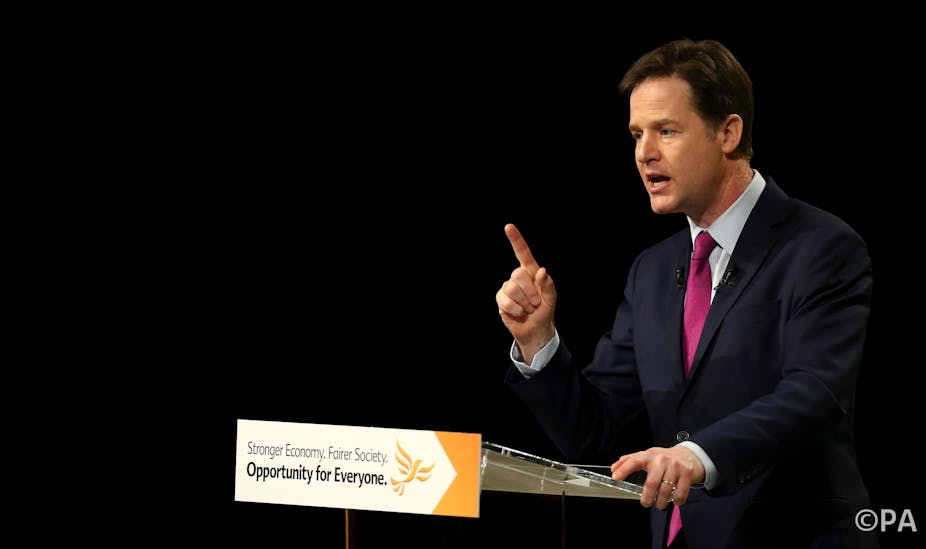

Democracy in action

And yet the party met for its spring conference in Liverpool in buoyant spirits. Their members and activists have proved remarkably resilient since 2010. While a third of their membership have left, the rest have stayed and continued to knock on doors and deliver leaflets like there is no tomorrow. They are happy to defend their party’s record in government and appear, on the face of it, ready to do it all again.

One of the key reasons for this is that the Liberal Democrats’ organisation is more democratic than Labour’s or the Conservative’s. Its members and activists feel that they have influence: for instance, last year, they overturned the leadership’s attemptto change its policy on airport runways. At this year’s spring conference, members had the opportunity to debate the minutiae of changes to the party’s constitution, the broad brushstrokes of which were agreed last year. Members also had chance to influence party policy on mental health, education and the environment.

The party is a fundamentally different outfit to its Liberal predecessor. It has had a difficult time balancing its democratic ideals with professionalisation. As experts note, the Liberal Democrats have had to move from “sandals to suits”. But the party retains a sincere commitment to federalism which is lacking in other governing political parties – and it seems to be genuinely appreciated by its grassroots membership.

Key moments (in the political bubble)

There were a few key moments at this year’s spring conference was opened by the party’s new president, Sal Brinton. Her predecessor Tim Farron gave an interview to the Financial Times which criticised the Liberal Democrat leadership, earning him a slap-down from Paddy Ashdown. The party had a special phone bank to allow members to campaign over the weekend. Several important policy announcements were made; notably, an extra £1.5 billion for child mental health services. And Nick Clegg’s speech was described by Channel 4’s Michael Crick called “one of the best speeches I’ve heard from a party leader in years”.

But little of this will be noticed outside of the political bubble. While people once got angry with the Lib Dems, they now no longer care. As Rafael Behr commented recently: “one difference between opposition and government for Liberal Democrats has been that, before coalition, no one noticed what they said; now, no one notices what they do.” The 23% that the party polled in 2010 is now a distant memory. If their number of seats reaches double figures after May 2015, it will be a good result.

Relentless optimism

The Lib Dems have now resorted to their old tactic: relentless optimism. They accuse commentators of wrongly predicting doom at every election, and this time is no different. Polling showing them losing key seats is unfair to their respected candidates, they claim. While this argument has some weight, the party’s own private polling has been roundly criticised, and is hardly the epitome of methodological rigour. There is also something quite depressing about resorting to “private polling” as a reassurance mechanism. It’s somewhat akin to England’s cricket coach Peter Moores reassuring you that his team is performing well in training.

The Liberal Democrats will lose seats at this election. How many they lose will depend on how their existing MPs hold on to votes in key marginal constituencies. And yet it is still possible that they could remain in government and continue to exert a bit more influence than voters give them credit for.