Following the devastation of twin atomic attacks, Japan announced its unconditional surrender to the Allied forces on August 15, 1945. Seventy years on from that momentous day, the war continues to haunt the peoples of East Asia.

In the West, it is often forgotten that 1945 marks the end of not only the second world war but also of a much longer period of political and social upheaval. When Japan attacked Pearl Harbour in December 1941, it had been in open warfare with Chinese forces for more than four years. Japan had made Korea a colony in 1910 and had taken control of what is now Taiwan [in 1895](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_invasion_of_Taiwan_(1895).

Japan was far from the only aggressive power in Asia. European empires had expropriated land and treasure from Asian peoples for hundreds of years. Defeat did not just mark the end of Japan’s imperial ambition, it was the beginning of the end for imperialism in Asia.

This political reality should make commemoration of 1945 a positive and forward-looking time for a region that is so dynamic and increasingly economically integrated. What might have been a time for the region to congratulate itself on how much it has achieved in the span of a human lifetime has instead become a point of very real tension among the region’s major powers.

This is in part because the war and its end created many of Asia’s flashpoints. Korea was divided in a hasty meeting between Soviet and American military officers. The islands in the East and South China Sea are disputed precisely because colonisation and war made their political provenance extremely murky.

Where does Japan stand 70 years on?

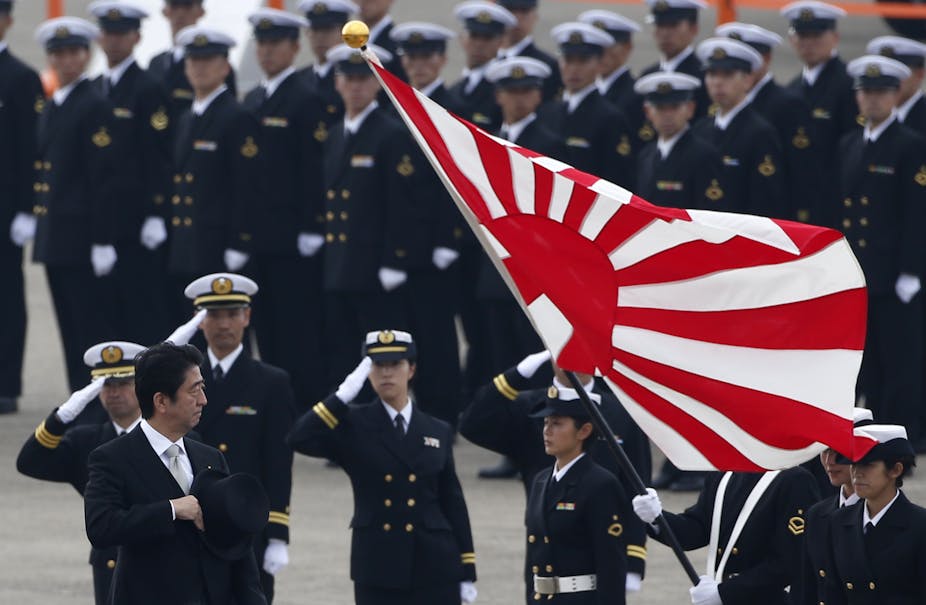

The underlying source of tension today lies in the politics of the past and in particular the sense that Japan has not fully accepted responsibility for its actions. Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe signalled long ago that he would issue a statement to mark the anniversary. He appointed an expert panel in February to inform the speech, which provided its report on August 6.

Prime ministerial staff have spent huge amounts of time and energy as they try to get the content and optics of the speech right. It is of such importance because of the messages it will send about what Abe is trying to achieve in Japan more generally.

It matters also because of what use will be made of these messages by others. Highly critical responses to the expert panel’s report from South Korea and China show how closely Japan is being watched and the level of political investment Korea and China have in Japan’s attitude to history.

The conservative Abe has made clear that he wants Japan to move on from the post-war political consensus. Japan’s Constitution, hastily written by the Americans and forced on Japan as part of the peace settlement, strictly constrains Japan’s ability to use its military. Abe has continued the process of re-interpreting the text to allow Japan’s “Self-Defence Force” to do more, but it is plain that he would like to change the Constitution altogether.

Equally, Abe feels that Japan should no longer fixate on what it did wrong in the past and should instead be proud of the prosperous, peaceful and democratic country it has become. Perhaps most importantly, Abe comes out of a part of Japan’s political spectrum that feels it has apologised enough at this point in time.

What will China make of it?

The Communist Party of China has made humiliation at the hand of rapacious foreigners a fundamental part of modern Chinese nationalism, with Japan as the principal culprit. In the cruder parts of the Chinese media, Abe is portrayed as taking Japan back to the 1930s. His grandfather’s participation in wartime cabinets and role in slave labour operations in Manchukuo in the 1930s is painted as an indelible stain on his character.

Abe’s statement thus has to try to reconcile his ambitions for Japan, his own political support base, which resents the apologetic tone of Japan’s relations with the world, with an increasingly assertive China, which will happily make the speech grist in the Communist Party propaganda mill.

The contents of the speech have already come in for extraordinary speculation. Analysts wonder what exact turns of phrase will be used and what these will signify about Japan’s approach to its past and future. Many wonder whether Abe will use the same words as the famous 1995 and 2005 speeches in which Japan acknowledged its aggressive colonialism.

The central issue is whether or not Abe will be contrite and apologetic. The signal from Tokyo so far is that he will reiterate the sentiments of the 1995 and 2005 statements and recognise Japan’s aggressive past, but he is unlikely to do enough to assuage critics at home and abroad.

China itself will mark the anniversary in bombastic style in Tiananmen Square. A massive military parade to mark the occasion of Japan’s defeat will be used to underline the nationalist credentials of the Chinese Communist Party and its successful stewardship of the country. The message will be clear: because of the party’s rule, China will never again be taken apart as it was in the past.

In 70 years, Asia has been transformed. The nations and peoples of the region have made huge advances, economically and politically. Yet notwithstanding the growing economic ties, the region is becoming increasingly nationalistic, as the anniversary shows so clearly.

Perhaps worryingly, this nationalism is paired with a growing militarisation of the region’s international politics. Defence spending is increasing dramatically and the emotional language of national identity is making the management of complex territorial disputes ever harder.

While we are not yet in touching distance of war, the region is taking clear and unmistakable steps towards a future of open geopolitical contestation. The anniversary of 1945 should serve as a sober reminder of what lies in store if military competition becomes Asia’s defining feature.