When sport and drugs are involved, often hyperbole is not far away. “This is not a black day in Australian sport, this is the blackest day,” opined the former head of the Australian Sports Anti-Doping Authority (ASADA), Richard Ings, regarding the release of a report into corruption in Australia.

This remains to be seen.

The media frenzy that occurred following the release in Canberra last Thursday of an Australian Crime Commission (ACC) report Organised Crime and Drugs in Sport swept up athletes and clubs and sponsors in a whirlwind of accusation. Club executives had the look of rabbits in the headlights as they tried to come to terms with a report that was strong on rhetoric but short on public detail.

“Don’t underestimate how much we know…” the Justice Minister, Jason Clare thundered, hinting darkly at the existence of fat but confidential briefs of evidence that would incriminate officials, players and clubs in illegal drug taking, links with organised crime and match fixing. What on earth are peptides anyway? The trouble with all this was there was and is an alarming absence of detail. Who are the clubs and players and officials involved? The ACC had reported confidentially on some of this to governing bodies but this left most none the wiser.

The media abhors a vacuum and so from the time of the report’s release it was desperate to fill out the detail. Given that the day before the report’s release, the AFL club Essendon had owned up to ASADA about its concerns with its own sports science program run by a sports scientist named Stephen Dank, some in the media felt they had their man.

“Revealed: The murky world of Dr Peptide” shouted the front page of Fairfax Media’s Sydney Morning Herald. The Australian was looking at “‘Dodgy’ scientists outside the rules.”

In the Fairfax story, Nick Ralston, Lisa Davies and Rachel Olding said they would “reveal the murky world of sports consultant Stephen Dank” and went on to discuss Dank’s role as one of the owners of the Medical Rejuvenation Centre at Bondi Junction that “sells anti-ageing medicine and sports performance supplements”.

Stephen Dank had worked with Essendon and coaches James Hird and Mark Thompson as well as high performance manager Dean Robinson. He had also worked with several NRL clubs.

He strongly denied that his work involved injecting players with banned peptides or indeed using illegal substances on players at all.

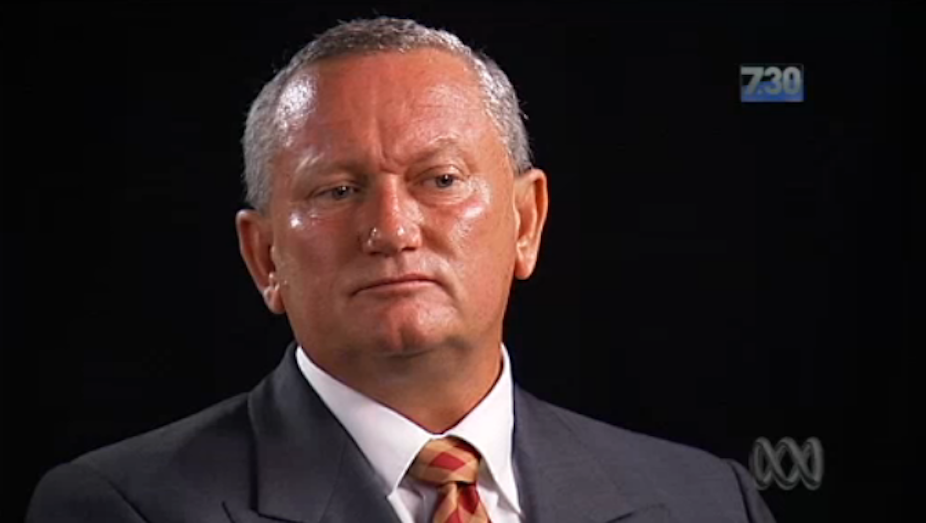

By the end of last week, Dank was fighting back hard. Last Friday he gave an interview to the ABC’s 7.30, which screened on Monday night. On Sunday night his lawyers announced that he was suing. “Multiple proceedings for defamation, injurious falsehood and financial loss are being brought in the NSW Supreme Court against the media on behalf of Mr Stephen Dank, Mr Ed Van Spanje, Mr Adam Van Spanje, Mr Zaheer Azmi and the Rejuvenation Clinic Bondi Junction,” his lawyers said in a statement.

The practice of having a lawyer threaten legal proceedings in order to try and shut people up or stem the flow of negative comment and innuendo is not an uncommon tactic for those who feel embattled. Was this just a scare tactic?

Last night Dank gave his side of the story to 7.30. He comprehensively denied using any illegal substances, peptides or others on players at Essendon, stated that the coaches knew exactly what he was doing and furthermore some of the coaches themselves had used banned substances, as they were not subject to World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) rules.

If Dank was bluffing then it was a strong performance. He added that the ACC had interviewed him and told him that he had done nothing wrong.

So where does this leave the media?

Defamation is a civil action. Plaintiffs must establish that material about them was published which injured or lowered their reputation in the eyes of others. It is not just the plain meaning of the words used but also the inferences or imputations that are contained within the words that the plaintiff can rely upon.

Dank will doubtless point to the imputations about his professional reputation contained in the media reports on his involvement with Essendon, as evidence of the defamation against him.

Defendants must then mount a defence against the action. The most common and effective is that the reports are true. However defendants are required to prove the truth of all the imputations contained within the words used as well as the truth of the statements on their face. This can be difficult.

If indeed he does actually proceed to litigate this, Dank’s interview on 7.30 would suggest that media outlets have a battle ahead of them.