As with Vladimir and Estragon awaiting Godot in Samuel Beckett’s play, those eagerly anticipating the arrival of the Mueller Report may have to adjust their expectations. There has been a palpable sense that, when the document finally comes, it will be a comprehensive and detailed tome. In reality, nothing in the conduct of the investigator and his team to date suggests that this will be the case.

Robert Mueller has run a tight ship, and there is now speculation as to whether his full written findings will ever be released to the public. Perhaps he is mindful of what has come before when a sitting president has been the subject of a major investigation. Kenneth Starr, who ran that investigation, suggested to The Guardian that “he [Mueller] is trying to avoid landmines”.

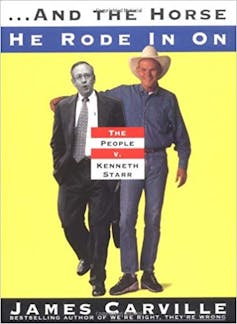

It is now more than 20 years since the independent counsel report on the Whitewater Affair was released. And yet, a mention of the name “Ken Starr” to any American over a certain age will bring an inevitable memory recall of the four-year zealous pursuit of Bill Clinton for a range of alleged transgressions from obscure land deals to sexual misconduct.

Fast forward to 2019, and the hype surrounding the release of the Mueller Report rivals that of any blockbuster. This time, the special prosecutor – as the role is now known – is tasked with investigating possible links or coordination between the 2016 presidential campaign of Donald Trump and the Russian government, as well as allegations of obstruction of justice by members of the Trump administration.

Hunting presidents

In some respects, parallels can be drawn between the two episodes – and Starr himself has said there are “eerie echoes” of his investigation in Mueller’s. A suspicion of misdemeanour by a man who will become president leads to the appointment of an independent prosecutor, much to the vexation of his supporters. Throughout the inquiry, the extent to which the process can be fair and non-partisan is fiercely contested. Furious allies declare a conspiracy, an apoplectic media splits along predictable partisan lines, and everyone else reaches for the popcorn.

But here the similarities end. Former FBI director and Marine Corps platoon commander Mueller was described by the BBC in 2019 as “America’s most mysterious public figure”. The 79-year-old avoids interviews and does not use Twitter. Significantly, his investigation has remained leak-free, dealing instead with the challenge of sensitive documents being hacked from outside.

Of those polled in February 2019, 56% said they trusted Robert Mueller, with 33% in the same poll stating confidence in Donald Trump. If, as is predicted, his report is imminent, this would mean the $25m exercise will have taken less than two years – record speed for a special prosecutor to reach a conclusion.

How a Starr was born

The Starr investigation was a significantly different beast, not least because the inquiry led by special prosecutor Robert Fiske into the Clinton affairs was already eight months underway when Starr took over. An interim report had been filed, which found that the former Arkansas governor had not acted unlawfully in the Whitewater land deal, and that there was no foul play regarding the death of White House special counsel Vince Foster. And there it should have ended.

But when President Clinton signed the Bill that reauthorised the Independent Counsel Act in 1994, the avenue for further investigation was opened – with no time or funding limit. The four-year, $39.4m Starr investigation began.

Characterised by leaks, and questionable decisions regarding how to deal with the media, the inquiry became increasingly melodramatic as villains, cheats, religious zealots and victims embraced their roles. At times, it seemed that the public, not yet consumed with new media, had a more measured take on the proceedings than those inside the Beltway.

As the investigation reached its climax, the president’s approval remained stubbornly high, helped not only by a buoyant economy but by the undeniable fact that a majority of the public held the prosecutor in such low regard. Gallup polls at the time of the Starr Report and ensuing impeachment showed public disapproval of Starr peaking at 62%, alongside 66% approval rating for Clinton’s presidency. Mueller aside, Donald Trump has never yet reached an approval rating above 58%.

The key difference between the Mueller and Starr inquiries lies, rather obviously, with the fact that the former has the potential to be the most, if not an even more, serious constitutional crisis since Watergate. The other was nothing of the sort – and if the public response to the Starr Report could be summed up in a sentence, it might be that lying about sex is more grounds for divorce than for impeachment. On the other hand, lying about complicity in alleged Russian interference in a US presidential election is a grave matter indeed.

But thanks to the toxic partisanship that now prevails not only in Washington DC but throughout the country, the penchant to believe that any stories that challenge either partisan narrative are “fake news”. In this era of tribal political warfare, this is potentially problematic for Mueller. The veracity of his findings may yet be rejected by those determined to choose their own truth.