The polls published in this election campaign may well be Kevin Rudd’s best friend. But to explain what looks like an absurd statement requires some background on the politics of polling itself. Any commentary or conversation that might inform us about polls rather than by them may help us understand what kind of democracy we are living in.

I am proposing to open this conversation here, as I don’t think we are having it.

And who better to start this conversation than the arch-populist of Australian politics: Clive Palmer himself.

On ABC Lateline on August 27, Palmer declared:

Of course the polls are rigged: Rupert Murdoch owns Newspoll and Galaxy Research, and the media set the agenda and try to determine the result of an election before it is held.

Palmer is at least half right, as I will argue below, and he has at least drawn attention to the role of polling in this election, even if he has ignored the fact that the polling business is less concentrated than media ownership in this country. But then again, it is not just the number of polls that are undertaken, but which news outlets publish them, and how influential these outlets are - which I guess takes us back to Rupert Murdoch.

In the past, sales of newspapers have always increased during election campaigns, and voters wanting to know how the polls are trending can be a large part of this. But what are voters interested in? Do they believe in the polls and want to use them as a guide to back a winner or an underdog? As a keen observer of media, I have noticed that reporting the polls during this election has figured much more prominently than previous elections. And I do think this is a worrying trend in Australian politics, that leads ultimately to disenfranchisement.

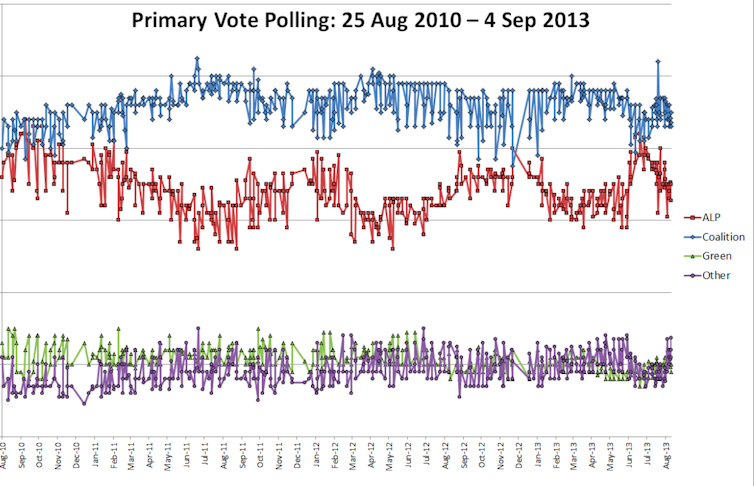

The problem is that when we are pounded each day with polling reports, they can begin to dictate public opinion rather than reflect it. Even when the polls are aggregated, they can turn into a kind of “poll worm” that, when it turns, can take on a life of its own, that could be a death spiral for one party or another. The poll worm may not be a reflection of what people think or, more importantly understand, about the policies, but nevertheless becomes the very soul of populism itself.

When we read the poll we stare very deeply into that soul - and it grips us completely. We might even lose interest in the election: “it is already decided”. Results, as a philosopher declared of the media in general last century, reflect “a circle of manipulation and retroactive need in which the unity of the system grows ever stronger”.

The problem with polls is that we have no way of knowing how much they are distorting our judgment of politics. We may intuitively know that they are, but we don’t know by how much. The polls may be real, they may be imaginary - we don’t know. But what we do know is that they really are the way we live our relationship to politics during an election campaign - yes, we do know that.

And the most influential force in the poll-led campaign phenomena by far are the tabloids.

Whilst many commentators will tell you that the so-called quality papers are the most influential because they are read by elites, this is not at all true in an election campaign. Tabloids are produced for their saleability, and in an election campaign that really does count.

Whereas the qualities can and regularly do defend the principles of the fourth estate - to make governments accountable and to provide deliberation over social and economic challenges - the tabloids are generally more apolitical. They are in touch with readers who are interested in a collective sentiment. But when the manufacture of collective sentiment becomes political, it is a game-changer.

Which takes us straight back to the problem of polls. It is not that polls can be wrong, it is that they are assumed to be about what people think. When we look at a poll, it is not what the poll tells us that is important, it is the fact of it being published at all, and the relationship that puts us into with other voters.

The sense of a shared public opinion is produced by the poll itself and not prior.

So, in one sense, “public opinion does not exist” at all, while at the same time it become decisive in electing governments or a party replacing its political leader as we have seen.

But public opinion is not homogenous and not all opinions are of equal value. When a poll asks for opinions rather than facts, it assumes firstly that all those polled have the same educational background, and that everyone will therefore have a well-informed opinion. In fact, some who are polled may not have an opinion at all: they may not see why the question - or even an election - is important.

So whilst a tabloid like Sydney’s Daily Telegraph claims to “know what its readers want”, there is a sense which it does not know its readers at all - and wouldn’t, even if it polled them. It only knows that each week it sells out in millions and is most popular precisely where it may not have to compete with education as an agent of socialisation. Its readership is very attached, because it offers something more than what to think about: that connection to a collective sentiment. It may be that it relieves readers from having to form an opinion at all, which may be a burden.

For this reason polling, or more precisely, reporting polls, is bad for democracy, which is highlighted by the fact that they may well prove to be Kevin Rudd’s best friend if he loses the election tomorrow. Have all the leadership changes in Labor damaged its image? Has Rudd mishandled this campaign? Is Rudd responsible for the disunity in the Labor party? These are all questions that may be decisive in a Labor loss, but the truth is we will never really know because that “poll worm” has already obscured the truth. When the polls become the news ahead of the actual policy, deliberative democracy is no longer able to support representative democracy.

Our electoral system recognises this problem in a small way by having a “media blackout” in the last few days of the campaign, intended to give people a cooling-off period in which they can make a decision without being assaulted by advertising.

But in conclusion, I would point to polls as a much greater threat to the democratic process. Private polling does no harm at all, but the reporting of polling should be banned during election campaigns. Then we might have at least some chance of knowing what voters really think in the one poll that counts.