In light of racially disproportionate stop and search practices, the case of Child Q and other accusations of misconduct, police in England and Wales are under pressure to address racism in their ranks. But their plan to do this through changes such as mandatory anti-racism training for all officers refuses to accept that the service itself is institutionally racist.

This is not just semantics. Barrister Abimbola Johnson, chair of an independent board overseeing police plans for race equality, advised that police forces must publicly accept that the label of institutional racism still applies. Without this admission, any promised reforms risk being dismissed by Black communities with low levels of trust in the police.

The race action plan, published by the National Police Chiefs’ Council and College of Policing, acknowledges racial disparities in stop and search and apologises for the “racism, discrimination and bias” that still exists within policing. But it avoids describing the police as institutionally racist, an omission which effectively rejects the findings of the 1999 Macpherson report.

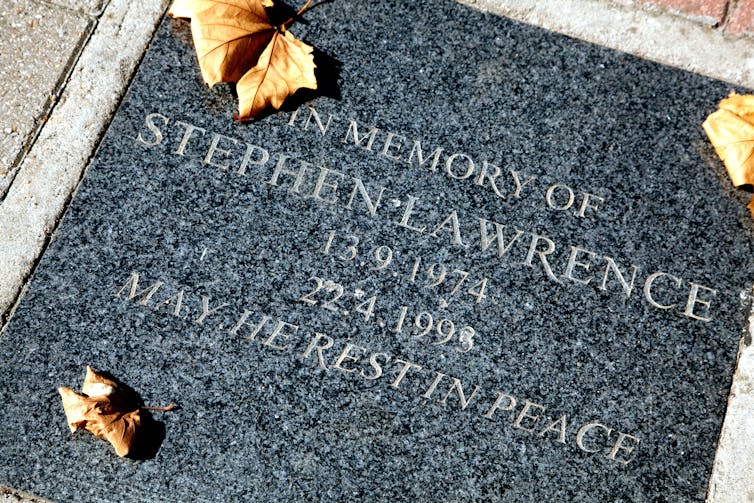

Commissioned after the 1993 murder of Black British teenager Stephen Lawrence, the report is arguably the most influential public inquiry on police behaviour to date. Its findings set the stage for a number of reforms on tackling racist crime, recruiting and retaining Black officers, and independent investigation of complaints against the police.

It defined institutional racism as “the collective failure of an organisation to provide an appropriate and professional service to people because of their colour, culture, or ethnic origin”.

The new action plan acknowledges police shortcomings in this regard, but avoids accepting the label of institutional racism. The plan commits the police to becoming an “institutionally anti-racist organisation”. But it is not clear how this is achievable while chief constables dismiss institutional racism as “a label that can be quite divisive”.

Andy George, president of the National Black Police Association, concluded: “It is unclear how their plan could deliver actions to something policing did not truly believe is real.”

Landmark reports

The question of whether the police are institutionally racist has been debated for years, such as during the 1971 trial of the Mangrove Nine. The trial, which acquitted Black British activists of incitement to riot charges from an anti-police protest the year before, was the first time the British judicial system acknowledged racial prejudice in the police.

Ten years later, a public inquiry concluded that anti-police uprisings in England were linked to widespread racial discrimination and aggressive policing. The Scarman report made a number of recommendations to make the police more accountable, but concluded that “‘Institutional racism’ does not exist in Britain.”

Little actually changed after Scarman’s report. Many of the recommendations were either ignored or not effectively implemented.

The conversation shifted in 1999, after a public inquiry, chaired by Sir William Macpherson, into Lawrence’s murder in 1993. The inquiry concluded there had been a failure of leadership by senior Met officials and numerous examples of professional incompetence in the police investigation that followed.

Most notably, the Macpherson report concluded that the Met was “institutionally racist”. Macpherson made 70 recommendations, of which 67 were implemented fully or in part over the following years.

Like Scarman, Macpherson refused to recommend ending police use of stop and search, contending it is “required for the prevention and detection of crime”. This is despite ample evidence that stop and search is discriminatory and ineffective. There was a brief reduction in stop and searches around the time of the inquiry, but it soon returned to similar levels of racial inequality.

Understanding institutional racism

Remedies that Scarman and others had proposed – such as changes in police training or education – focused on individual wrongdoing rather than broader structural issues.

Macpherson, on the other hand, understood institutional racism as a more pervasive issue, where racism is a product of how that institution “normally” functions. This is key to his support of the argument that racism cannot be addressed with responses targeted at extracting or educating “bad apples”.

The new action plan proposes mandatory training to equip police with the knowledge and skills to actively tackle racism within the service and society. But unless police culture and wider societal attitudes change, it is unlikely that anti-racist training as proposed for individual officers will have much impact.

Where are we after Macpherson?

One reason Macpherson’s inquiry had deeper understandings of institutional racism was the involvement of Black people describing their experiences of it. As one Black activist summarised: “We taught Macpherson and Macpherson taught the world”. But this lesson has not been acted on.

In the 23 years since Macpherson, there has been little evidence of fundamental changes in police organisational culture. Some critics argued that Macpherson’s generalised definition of institutional racism prevented progress. But there has also been a failure to situate the police within the broader structural racism of the state and institutions acting to maintain white supremacy.

Ignoring institutional racism contributes to wider attempts to portray Britain as moving beyond race-based disparities. The government’s controversial 2021 Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities also rejected the idea that institutional racism exists within Britain. Halima Begum, the chief executive of race equality think tank Runnymede Trust, criticised this denial as “deeply, deeply worrying”. She argued that it ignored the realities of life in Britain and further added to mistrust of authorities.

Read more: Race commission report: the rights and wrongs

A 2013 report by the independent police complaints watchdog concluded that the Met failed to deal with racist behaviour or to investigate complaints effectively. And, in 2019, the Met commissioner declared the police were no longer institutionally racist – while also admitting it would take over 100 years for the police to be representative of the communities they serve.

In 2019, Macpherson commented that, while police had taken steps in the right direction, “there’s obviously a great deal more to be done”. Grand proclamations acknowledging institutional racism in itself may not make much difference to how these institutions function, but accepting its existence is a vital starting point.