Despite its role in bringing on the financial crisis, debt continues to plague many of us the world over (just ask the Greeks). In the UK the appetite for debt is undiminished, with the run up to Christmas seeing new consumer lending hit a seven-year high.

As people struggle to repay their debts, online forums have increasingly become a place where we are getting together to discuss our problems. This is significant for a number of reasons, not least because it has led debtors to ask interesting questions about the nature of debt itself and whether it should be repaid. With Syriza sweeping to power on the promise of reducing the Greek national debt and even defaulting on it if necessary, it seems this is a question on the lips of many.

The rise of online forums

There have long been formal channels for debtors to get help. There are not-for-profit organisations such as StepChange and Citizens Advice, as well as hundreds of commercial debt management companies that a casual internet search will bring up.

The rise of online forums as a place to get debt advice represents something quite different, however. In the long history of borrowers’ difficult relationship with debt, the tendency has been for people to try to deal with their debts alone. For many, taking on debt involves not just an economic relationship but a moral one.

It has often been seen as shameful not to be able to repay what is owed. (Indeed, knowing this, and before the practice was outlawed, debt collectors used to try to coerce debtors into getting in contact by leaving notices with neighbours and employers.) Conventional debt advice and its understandable dependence on one-to-one, confidential relationships does not really change this situation.

New conversations about debt

But, as research I’ve been involved with has shown, on these forums what we see is a new and quite different kind of response to the problem of debt.

Part of the reason for this are some of the problems with conventional forms of debt advice. While demand for not-for-profit debt advice services may have recently fallen, this is from an unprecedented high, and many debtors are still likely to have to have to wait a long time to speak to debt counsellors. As for commercial services, their reputation remains poor. Despite a recent regulatory crack down, it seems that many problematic practices in the industry remain.

But there is more to it than that. My colleagues and I spent some time analysing the conversations that debtors were having online with each other. What we found is that this new form of debtor-led support is subtly different in character from conventional debt advice.

Advice becomes not just about offering the best practical solution to dealing with problem debt. Instead, practical advice is routinely mixed in with emotional forms of support. Borrowers who arrived hoping to find a way to get out of debt soon find themselves initiated into a debtor community. Living with debt becomes something that can be done and shared with others. This is something quite new for many people struggling with personal debt.

Should debts always be repaid?

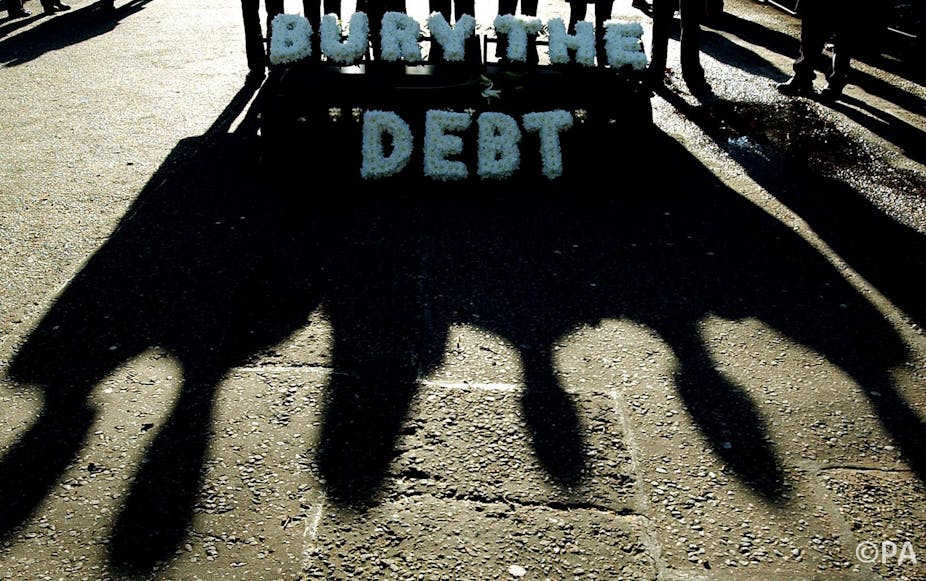

And then sometimes conversations begin to turn their attention to far bigger questions to do with assumptions that underpin the contemporary debt economy, something well beyond the remit of ordinary debt advice. One question, posed in a variety of different ways, stands out: should loans always be repaid?

As the anthropologist David Graeber has famously pointed out, the conventional wisdom that debt obligations should always be met is undermined by the simple fact that debt operates with the very assumption that often they are not. What this suggests is the existence of moral logics and economic logics about debt that are not quite compatible. This fact often goes unnoticed beyond the internal discussions of social scientists.

However, when not just academics and activist groups but ordinary debtors start talking to each other about these kinds of questions, we should sit up and take notice.

The social, political and economic consequences of what would happen if debtors everywhere stopped repaying their debts are almost unimaginable. We are of course a long way from that happening, even with recent events in Greece. But the situation is perhaps a little more fragile than we might think.