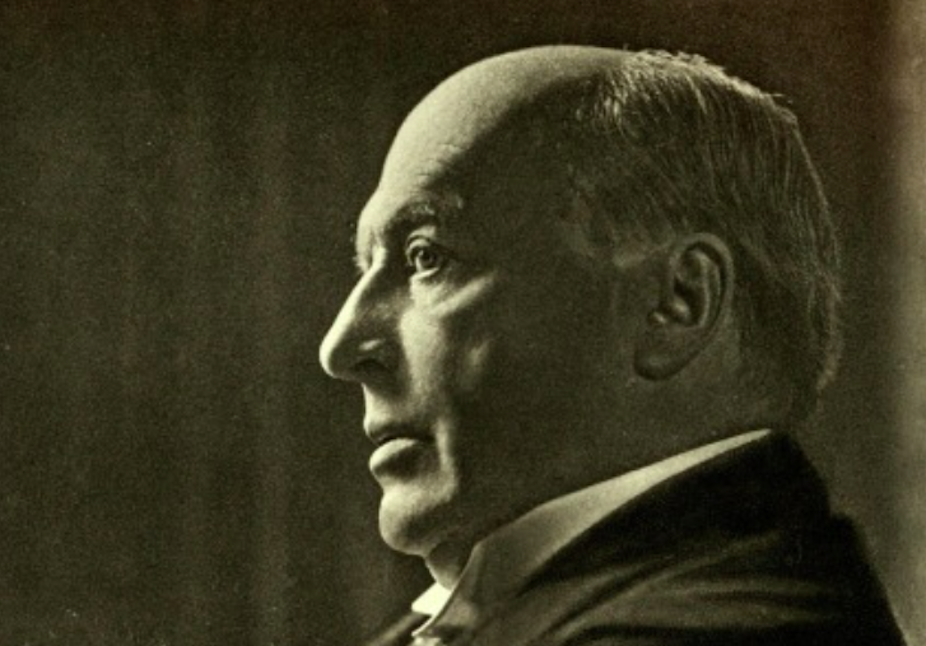

On the evening of December 1 1915, Henry James collapsed with a stroke at his home in London. At first it seemed that he would recover, but over the following weeks the renowned American novelist’s condition was far from steady. On some days he would be cogent and conversational, on others he would call in his secretary and earnestly dictate letters in the persona of Napoleon. At times, his hand would move across the bedspread as through he imagined he was writing.

His brother’s widow Alice braved the hazardous war-time Atlantic crossing to be by his bedside. Devoted literary friends such as Edmund Gosse and Edith Wharton visited or kept in touch. In January 1916, James was awarded the Order of Merit for services to literature over a 50-year career, during which he had written some 20 novels and over 100 short stories. But he was 73 and his strength was fading. He had a history of heart trouble and depression, and he found the anxiety and grief of wartime exhausting. He died on February 28 the same year.

One hundred years later, James’s cultural standing is higher than ever. His work features in classic paperback series and university reading lists, and has been adapted for film, television and stage. His private life has been scrutinised and reinvented repeatedly in biography and bio-fiction – sometimes more creatively than accurately. His fiction and letters – over 10,000 still exist – are both in the process of being re-edited and republished. There are two international societies for scholars who are interested in studying his work.

This would all have been a surprise to James and his publishers, who never made as much profit from his work as they hoped. Many of his later novels failed to recoup their advances, and latterly he made more money from short stories placed in magazines. Even in his lifetime, James had a reputation as a difficult writer for clever readers. In fact, this reputation was part of his value in the magazine market, where his name on the contents page added a touch of literary class – whether his stories were read or not.

Yet in a world of cut-throat literary reputations, the author of The Portrait of a Lady, The Turn of the Screw and The Golden Bowl has survived while contemporaries like Sarah Grand, Hall Caine and Marie Corelli who outsold him spectacularly have all but vanished. James often explored this mismatch between popularity and lasting value in tales such as The Figure in the Carpet. Shrewdly, he also saw that what readers respond to is not the real writer, but a persona which they buy into or construct.

James signs off

The last piece of writing James worked on before he fell ill was an essay about the young English soldier-poet Rupert Brooke. Brooke had died the previous April of blood poisoning on a troop ship in transit to Gallipoli, just weeks after the publication of his 1914 sonnets, including his best known poem, The Soldier. James knew him, and wrote to a mutual friend that this loss was so “stupid and hideous” that one could only “stare through one’s tears”.

James’s piece formed the introduction to Brooke’s travel essays, Letters From America, and was also a response to the mythology that sprang up around Brooke immediately after his death. In The Times, Winston Churchill had praised Brooke as the ideal of Englishness: “Joyous, fearless, versatile, deeply instructed, with classic symmetry of mind and body, ruled by high undoubting purpose.”

This obituary perhaps said more about Churchill and his agenda than about Brooke, however. Notably, it appeared alongside an appeal for more young men to enlist for military service. In contrast, James’s tribute focused on Brooke as a flawed human individual, while also making a strong claim that he be considered a “true poet” alongside Byron and Keats.

When Letters From America was published on March 8 1916, little more than a week after James’s death, this essay about the tension between a remembered person and a literary persona would have seemed even more poignant. Reviewing the book in the Times Literary Supplement the next day, James’s friend the biographer and critic Percy Lubbock said that the names of Rupert Brooke and Henry James were both “already a legend”, and “here run into one”.

Lubbock would later be appointed as James’s literary executor and given the tricky job of publishing his unfinished work and collecting his personal letters for publication. By editing and promoting his writing, Lubbock would play a major part in creating one of the most enduring versions of James, that of the serious literary craftsman and thoughtful, scrupulous student of human nature.

There are certainly many other versions of James, often contradictory: shy, self-assured, homosexual, heterosexual, altruistic, rapacious, self-aware and self-deluded. You might wonder where, a century on, we can ever find the real James. We can’t. Like his creation Hugh Vereker in The Figure in the Carpet, he has vanished, leaving us to puzzle endlessly over his rich and multi-layered work. That’s precisely the beauty of it, though. The fact that James’s work can be interpreted and reconfigured in so many different ways suggests that when we read his fiction, what we are really learning about is ourselves. And that, of course, is the hallmark of a great writer.