For centuries, male violence and acts of aggression were often the way that power was understood and patriarchy upheld. In contemporary times, in more moderate societies, this has become somewhat tempered, yet it still exists in different forms and has now been given the name “toxic masculinity”.

This phrase has long been used by academics to define regular acts of aggression used by men in positions of power to dominate people around them. In the late 1980s, Australian sociologist Raewyn Connell described the ways that white middle-class men used their power and positions to suppress traditionally socially marginalised groups such as women, gay men and working-class men. This idea has since been extended to include other behaviours, such as aggressive competitiveness and intolerance of others.

Now, in the wake of recent movements supported by celebrities and public figures, and the alleged sexually abusive behaviours of some prominent men coming to light, the idea of toxic masculinity has started to gain more currency in wider society.

One of latest talking points has been the release of a short film by Pixar which addresses the issue. The animation focuses on a pink ball of wool named Purl and how “she” tries to fit in at as a new employee at B.R.O Capital. Surrounded by suited white men, Purl struggles to fit in – even being told: “You’re being too soft. We gotta be aggressive.”

The Pixar film comes just weeks after an advertisement for Gillette razors. But while Pixar has been praised for telling a “powerful story” in a “strikingly direct” manner, the Gillette advert has faced criticism. Gillette’s advert appears to suggest that behaviours that some men regularly engage in, either in public or the workplace – including bullying, unwanted touching and catcalling – is inappropriate. What is more, the message seems to be that these behaviours should be explained as being inappropriate to boys in childhood.

Gillette’s apparent criticism of a domineering and aggressive form of masculinity has angered some, who consider it “anti-men”. Journalist Piers Morgan, for example, fumed: “What Gillette is now saying, everything we told you to be, men, for the last 30 years is evil. I think it’s repulsive … the implication we all have something to apologise for? Shut up, Gillette.” Others have also suggested that this is just another example of “traditional” forms of masculinity being threatened in general.

Threads of toxicity

But what is this “traditional” masculinity that might be under threat? Acts of aggression and a need to dominate others might often be considered as natural behaviour for men – especially for, but not limited to, those in power – and might even be considered a desirable attribute in some situations. But this idea, which is based on the assumption that more aggressive men have higher testosterone levels, has been widely refuted scientifically.

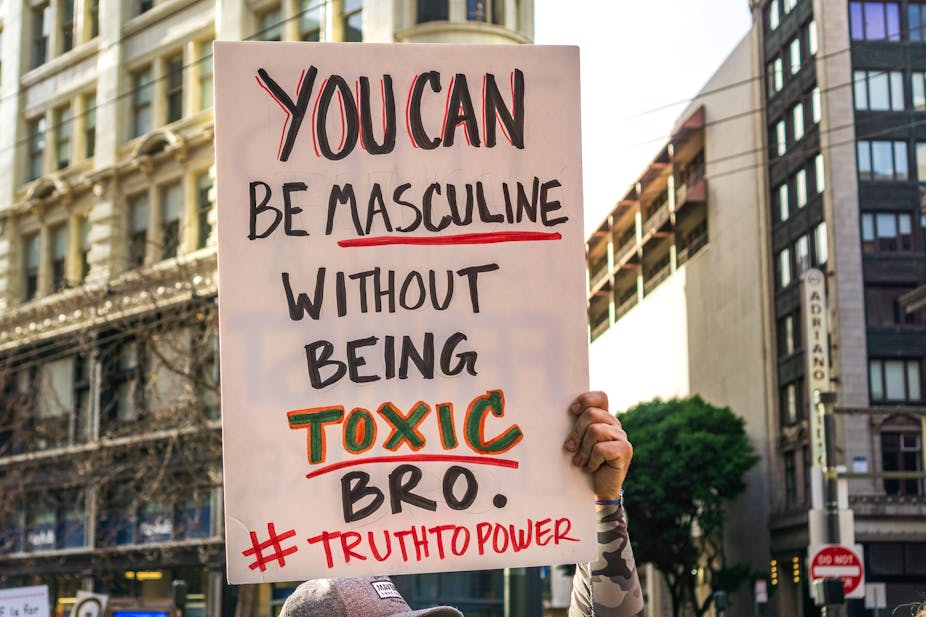

The recent increase in concern about toxic masculinity has come from several quarters. As the celebrity-backed Time’s Up movement continues to call for an end to sexual harassment and inequality in the workplace, the Everyday Sexism project collates day-to-day experiences of those who have suffered the consequences of toxic actions.

Meanwhile incidents of violence and aggression from high school shootings to road rage have been characterised as examples of toxic masculinity – but there are more common acts of male aggression that might better illustrate the extent of the problem. These include women being made to feel unsafe in public, due to unwanted attention from men. It can also be more subtle than that, presenting as men making public comments to women which are often sexual and derogatory.

Men victimised

But women are not the sole victims of toxic masculinity, men can be affected just as deeply by these acts. Even if men are not directly targeted by an act of toxic masculinity, the culture of it can force them to suppress their own feelings, in order to fit in with narrow expectations of masculinity that suggest emotions are weak. Under this idea, men are naturally physically strong and those who are “weak” are “snowflakes”.

Warnings that a backlash against male behaviours that are considered to be “toxic” will result in a society where “boys will not be able to be boys” misses the point and suggests that to be a man necessarily means to be aggressive and domineering.

Just as not all men perpetrate acts of toxic masculinity, not all fit a standard mould of manhood. Many men might be struggling with their sexual identity, or have never had opportunities afforded to others because of their social class. They might not be working, or are parenting their children full time. They might also be men who at some point, have been subject to toxic comments or violence from other men.

There needs to be far greater recognition that the way that some men – especially powerful and privileged men – express their masculinity is not the only way. As well as greater recognition that the term “masculinity” itself is dynamic, not fixed. Arguably, there is no “right” way to be a man.

Rather than engaging in toxic practices, men who are in privileged positions should be able to recognise that they can be agents for change, to the benefit of all. This is a message for everyone – there is no new “war” on men, and there is no need for anyone to “prove” their masculinity through aggression, and its time to put an end to toxic masculinity.