At the end of a long and challenging week, the famous aphorism, “we have met the enemy and he is us” readily comes to mind. The issuance of the long awaited Senate “torture report” has set off a debate in Washington and the press, the likes of which are rarely seen. It is hard to recall an issue on which so many have weighed in, even in the sensationalist and polarized cauldron in which domestic politics now operate.

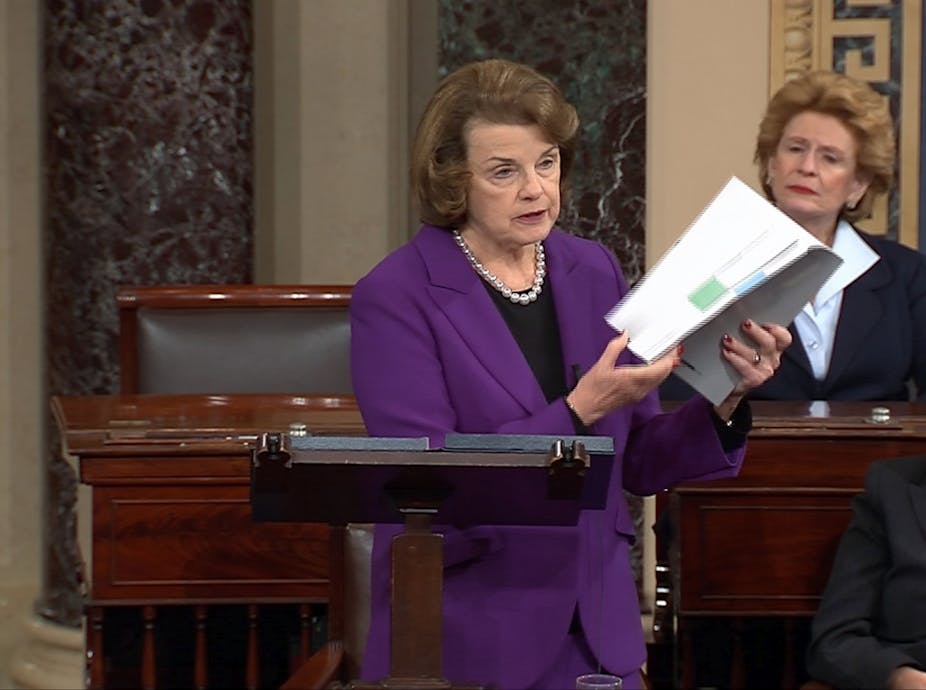

The week has been replete with pantomime heroes and villains. John McCain’s speech on the floor of the Senate may go down in history as his finest hour (although I confess that the cynic inside of me wondered if it was the opening speech in his 2016 run for the presidency, given his recent hint on the Colbert show that he may do so). Diane Feinstein handled herself adeptly and with some dignity, even if she lacked McCain’s poetic qualities.

The villains, as is generally the case in pantomimes, were more glaring and appeared more outrageous. Dick Cheney (who can always be relied upon to speak with authority and without a hint of shame) argued that our actions were defensible, legal and justifiable. A series of current and former CIA officials argued the same. Former president George W. Bush proclaimed ignorance, a claim that will keep many comedians in business for the next several months. Alberto Gonzalez, then Attorney General, popped up to be interviewed in several quarters. But he was generally asked about what the then President knew, not why he was MIA when the law was apparently being broken. But Wolf Blitzer’s question to Diane Feinstein about if she would feel guilty should an American be killed as a result of the report being made public may be, to my mind, most memorable in providing a new journalistic low point.

National values vs. national security

It was hard to get past the horrific substance of what was being debated. But if you could, it was ironic to watch these people who often use the word “academic” as a term denoting something marginal to the real world, debating academically.

What is the definition of torture? When are you ethically justified to inflict such pain and humiliation on the enemy? Do the ends justify the means? Is there a threshold? Is our legitimacy abroad a question about which we should care? What is the statute of limitations on when you can stop caring about past high crimes and misdemeanors?

The last question, of course, presumes a crime took place. The current director of the CIA, John O. Brennan, obviously disagrees when he says that they might use such methods again. This comment leaves President Obama in an awkward position, given the fact that it contradicts both Brennan’s reported statements in 2009 and the president’s more recent statements. When this storm is over the President may find himself having to look for a new director, although the list of applicants may be short in the current climate.

Americans have generally identified the central question that they currently face as being the relationship between their core values, their national security considerations and the way in which their foreign policy institutions operate. We have again been reminded of Benjamin Franklin’s adage that “Those Who Sacrifice Liberty For Security Deserve Neither.”

In this case the question is a more subtle one, because it concerns how we treat foreign prisoners -– and the lessons we learn from this episode.

The long-term costs of not acknowledging dark episodes

We’ve been content to maintain Guantanamo and avoid instigating routine judicial proceedings against our captives for over a decade, arguably in abrogation of our laws. Now we discover that we have tortured many of them, certainly in abrogation of international laws if not our own.

The question now is, at what point do we decide to return to what we are constantly told are our core values –- such as the rule of law? Being shameless about the flouting of those values in the name of national defense, ignoring it in a wave of jingoism or denying its occurrence are all tactics that can work in the short term. But can they work for us as a society in the long term?

The events revealed in the report provide an important mirror on our society since 9/11. These events are not isolated. They are part of a trend and just worse by a matter of degree. The way we talk about and treat undocumented immigrants; the way we talk about Muslim citizens; indeed, the way we talk to each other. All have degraded in the three decades that I have lived in this wonderful country.

I also know that these events are peanuts when compared to other “atrocities.” But other countries have discovered such responses all have a long term cost when not acknowledged.

Although on a far greater scale, the costs of the Japanese refusal to recognize their terrible treatment of Korean “comfort women” rumble on decades later. The unacknowledged barbarism and guilt of the Balkan War is still evident every time two soccer teams from those countries take the field to play each other.

All countries have their dark episodes. Not all are as well publicized. The British held refugees captive in internment camps in the frozen Canadian tundra in World War Two (full disclosure: my own father was among them). Many of them died, either in transportation boats sunk by German U-boats or in the camps. The Americans did the same to citizens, residents and visitors of Japanese ancestry. In both cases, nobody was held accountable.

The key question, that few are asking, is where do we go from here? Is this simply a blip – and then we return to the status quo? Does Guantanamo stay open, passing on the problem to the next president? Does our national security continue to justify reduced rights and liberties – for ourselves as well as for undocumented migrants deported as a result of anti-terrorism legislation? Or is this a watershed, after which things will change?

After three decades living in this country, I am always amazed at the unanticipated speed at which trends can alter in the United States. Harvard professor Samuel Huntington wrote a book about American politics in 1983 in which he argued that there was an inherent tension between American core values and the way that its foreign institutions, like the CIA, operate.

When the gap becomes too great, he argued, we get a period of righteous outrage marked by widespread protest. Under the weight of this outcry, the institutions bounce back and function in a way more consistent with our values. The catch, Huntington argued, was that this realignment made us weaker abroad. I guess we can regard the current climate as a good test of his claim.