Barts Health is the biggest NHS trust in the UK with a turnover of £1.2 billion a year and in charge of running St Bartholomew’s, Europe’s oldest hospital. But since January it has lost its finance director, chief nurse and chief executive. Whatever face-saving spin they may put on it – the trust’s finances weren’t mentioned in any of the resignations of these three senior managers – their departures certainly seem connected with financial and managerial problems.

The trust is deep in debt, sinking deeper, with projected deficits for 2014-15 rocketing upwards from a previous figure of £43m to £93m, according to its February board papers – or even as much as £100m.

It’s also facing at least one, possibly two highly critical reports from the Care Quality Commission. It’s struggling to recruit and retain nursing and other staff and in the meantime is spending more than any other English trust on agency staff.

Private financing

The financial problem has been a ticking time bomb ever since what was then called Barts and the London Hospital Trust was given the go-ahead in 2006 to sign up for a costly £1.1 billion scheme to redevelop both Barts Hospital and the Royal London, financed under the ruinously expensive Private Finance Initiative (PFI). Believe it or not, the £1.1 billion scheme was in fact a scaled-down version of the original plan, which had mushroomed in size to a staggering £1.9 billion.

Patricia Hewitt, then former secretary of health, rejected the £1.9 billion plan, but gave the nod to a new one that mothballed 250 of the beds – 20% of the planned capacity – to save costs. Three floors of the new buildings that were to be built were subsequently “shelled” (left empty) to reduce the cost.

But like smaller PFI schemes, the actual cost to the trust isn’t really £1.1 billion, but much more, with a legally binding contract stipulating inflation-linked instalments, rising every year, for the next 35 years. The “unitary charge” payments – the payments made for the initial capital and ongoing maintenance costs – for both the building and for non-clinical support services started high at £109m per year. But these payments will keep on rising, regardless of how much revenue flows into the trust. Treasury figures show that the PFI development eventually cost £1.15 billion; so far £675m has been paid back, but another 33 years will come to, at the very least, £6.5 billion by 2048.

Of course the contract was signed back in the midst of Labour’s year-on-year increases in NHS funding, when it seemed that the good times might go on for ever.

Taking on more hospitals

But in the aftermath of the banking crash and the abrupt turn to public sector austerity to pay for the bank bail-out, the unitary charges that would have to be paid began to seem much less manageable. So when the new buildings came into service in 2012, the trust was not only running the historic St Bartholomew’s (Barts) Hospital itself in Smithfield and the newly rebuilt Royal London Hospital in Whitechapel, but it had also taken on two busy general hospitals in Newham and Whipps Cross.

The inclusion of the combined turnover of £413m from these two hospitals effectively expanded Barts Health’s total revenue by more than 50%, and brought in the prospect of more income. At first, then, it appeared that the PFI payments would reduce as a proportion of trust turnover, from 16% to a less scary but still unaffordable 11% of the Barts Health budget.

But under the pressure of the longest-ever freeze on NHS spending, which could continue at least until 2021, and plans for even more massive savings in the next few years, Barts’ financial plight has steadily worsened.

The tariff paid for each treatment is being scaled down by up to 4% each year. And with local commissioning groups seeking ways to limit the number of people seeking hospital treatment and levying financial penalties on trusts that treat more patients in A&E than planned or fail to hit target times, the trust has been left with no leeway to deal with future financial pressures.

Running scared

The quest for cost savings has driven managers into short-sighted moves, such as down-banding nursing staff, and cutting services and quality of care. And impatient managers, trying to dragoon staff into working harder for less, and fearful that they might face angry local reaction if their cash-saving plans were publicly known, cracked down on any sign of dissent.

The bulk of the cuts could be expected to fall on Whipps Cross and Newham hospitals, since these sites are predominantly NHS-owned, allowing buildings to be closed or land to be sold off. Any cuts in service in Barts and the Royal London Hospital would still leave the steadily rising unitary charge to be paid.

In 2013, Charlotte Monro, chair of the Whipps Cross branch of UNISON, who had 26 years of unblemished NHS service, was suspended and then sacked on trumped-up allegations after speaking out over fears for older people’s services. But speaking at a February board meeting about the CQC reporting that staff were afraid to speak for fear of “repercussions”, Morris was clearly unable to recognise the impact of such cases.

Stories of bullying and intimidation of staff at Whipps Cross and elsewhere in the trust have continued. Last year Barts Health commissioned a review by Duncan Lewis – presented to the board – which identified bullying and race discrimination as key issues, with no apparent action against guilty managers. But not enough seems to have changed on the ground and staff fears of speaking out were a factor in critical CQC reports, which have not yet been published.

Future still looks bleak

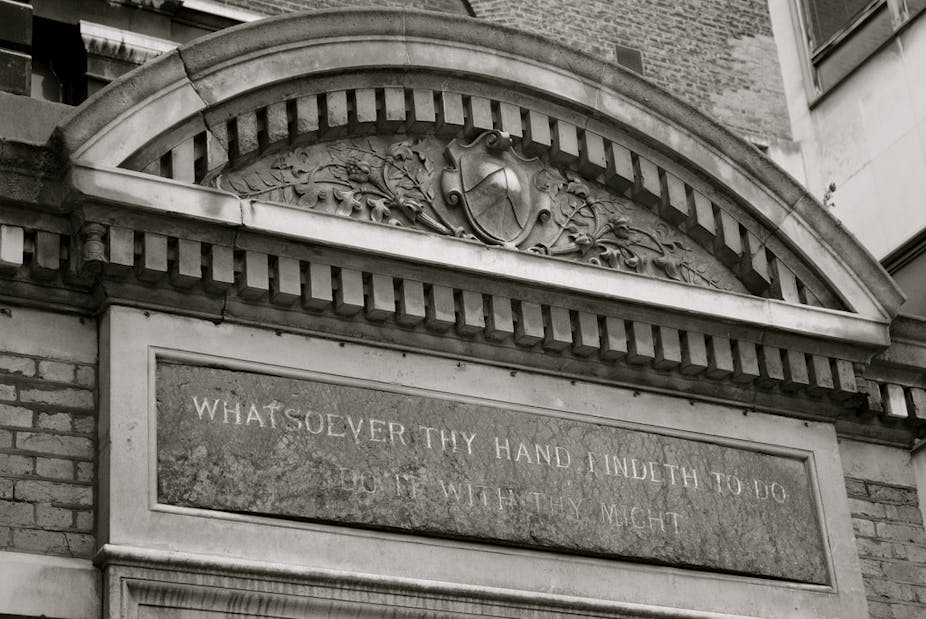

There always was a supreme irony in building one of the world’s most extravagant and costly hospitals in one of the most deprived boroughs in England. Now as the need for healthcare continues to increase, the trust’s future is increasingly bleak.

The East London Clinical Commissioning Groups have drawn up a strategy which starts from the need for the CCGs to make savings of £128m over five years – but notes that local NHS trusts are facing much bigger proportional savings targets totalling £434m, of which £324m has to come from Barts Health.

The plan envisages this requiring more “productivity” increases, alongside cuts, closures and sale of hospital sites – and this inevitably means cuts and closures in Whipps Cross, Newham and the London Chest Hospital.

In desperation the Barts Health board has been splashing out £500,000 per month on management consultants – £7m in 14 months. But as the deficits keep mounting up and the pressures on the trust keep growing, many will feel this is throwing good money after bad.

The only way out for Barts is for the government to step in and force a renegotiation of the PFI contract to reduce payments to a fair and affordable level. Otherwise a debt-laden flagship hospital project could soon drag down health services for more than a million Londoners.