This is the first of four articles in the series on Civil Registration and Vital Statistics (CRVS) in Indonesia entitled “Data that Records and Protects All”.

Six years into her marriage, Bunga (not her real name), a 20-year-old resident of a district in South Sulawesi, has only now realised the importance of having the state recognise her marriage through a certificate.

Bunga’s marriage wasn’t recorded because she got married when she was 14. The Indonesian Marriage Law states the minimum age to marry is 19 for women.

Bunga and her husband decided to have a customary wedding, one that is not registered at the civil registration office.

Without a marriage certificate, Bunga cannot obtain a family card (Kartu Keluarga or KK). Bunga’s parents, who are poor, do not have the card either.

Now her husband is missing, and without a marriage certificate and KK Bunga cannot apply for a birth certificate for her two-year-old child.

Although they are both eligible, because they are not officially recorded neither Bunga nor her child has been able to access the National Health Insurance (JKN) service, which is provided for free by the government, or any social assistance during the pandemic.

Bunga’s family is among the one in four households with children under 5 in Indonesia who struggle because they are not registered, so the state has not legally recognised their existence.

Part of the problem may be low public awareness of legal identity document ownership.

However, our research at the Center on Child Protection and Wellbeing, University of Indonesia (PUSKAPA), shows more systematic problems contribute to this phenomenon.

These problems include the civil registration service not being accessible to poor and vulnerable communities, such as people with disabilities.

Economic inequality

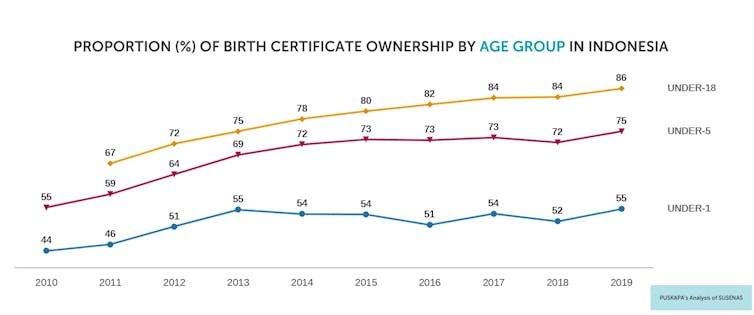

PUSKAPA’s analysis of Indonesia’s 2019 National Socio-Economic Survey (SUSENAS) data suggests 14% of children under 18 do not have a birth certificate. The proportion goes up to 25% for children under 5, and 45% for children under 1.

We also found only 5% of children under 18 living in high-income households don’t have a birth certificate. On the other hand, around 23% of children under 18 who live in poor households do not own the certificate.

These figures show economic inequality is indeed a problem in the civil registration system.

The lack of means to pay for transportation to reach the nearest civil registration office remains an obstacle for poor families. Our second article will further discuss these obstacles.

In addition, we also find disparities in birth certificate ownership between urban and rural areas.

The percentage of children without a birth certificate is higher in rural areas (18%) than in urban areas (10%).

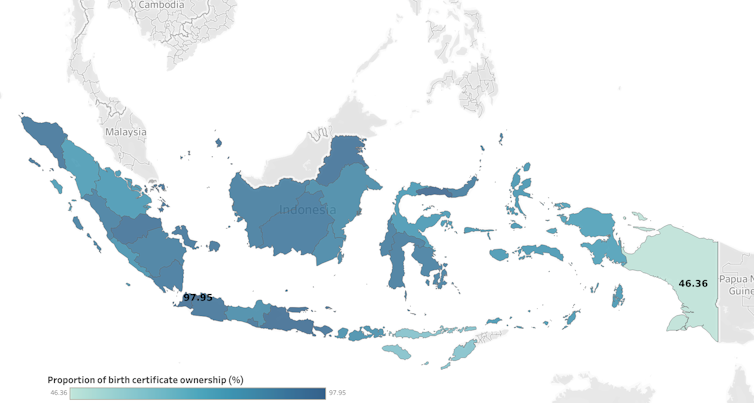

According to recent data, about 54% of children in Papua don’t have a birth certificate. Papua is Indonesia’s eastern-most region and one of the most underdeveloped.

In the nation’s capital, Jakarta, almost all children (98%) have a birth certificate.

Our paper in 2016 shows some residents of Langkat, North Sumatra, have to travel up to three hours to reach the nearest civil registration office to obtain a birth certificate, and another three hours to get back home.

The government has made efforts to simplify the process and bring civil registration services closer to the community. However, lack of capacity, infrastructure and supporting facilities remain as obstacles.

For instance, a shortage of electronic ID card blanks and the absence of computers or printing equipment are problems at various civil registration service locations.

Vulnerable groups

Beside the poor, other vulnerable groups also risk going through life unrecorded.

A 2014 study, which we carried out under a partnership between the Indonesian government and the Australian government for programs endorsing the values of justice (AIPJ), reveals children whose parents or caregivers live without physical disabilities are five times more likely to have a birth certificate than those whose parents or caregivers live with disabilities.

Offices that are not disability-friendly and complicated procedures make it difficult for people with disabilities to apply for and obtain legal identity documents.

In 2016, we conducted a similar study with Governance for Growth (KOMPAK) in different areas. We found the likelihood of having a birth certificate increases with the applicant’s education level.

Those with higher education are assumed to have a higher awareness of the importance of legal identity documents because they want to make sure their children can apply to schools.

The impact on citizens’ rights

Currently, around 17 public services require legal identity documents for access. These include schools, health insurance, judicial services, banking services, transportation, clean water, and electricity services.

Our 2016 study shows one legal identity document is the prerequisite to obtain another document.

Similar to Bunga’s experience, a person without one type of legal identity document might have difficulties obtaining the other documents.

Not only are legal identity documents needed to access services in ordinary situations, they are crucial for verifying eligible aid recipients during and after a disaster.

The distribution of government assistance to victims of the 2018 earthquakes in North Lombok, West Nusa Tenggara, and Sigi, Central Sulawesi, faced challenges due to the fact not all residents have a National Identity Number (issued together with their KK and birth certificates).

Improving the CRVS system, including civil registration and population data management, is an important first step in ensuring fair and appropriate implementation of various government programs.

The unregistered population in the system can lead to inaccurate program budgeting and planning.

The lack of legal identity documents also makes it difficult for citizens to prove who they are and what they are entitled to.

Until the government guarantees the registration of every citizen, the rights of Bunga and other vulnerable people are not protected completely.

The studies and programs related to this article were conducted in collaboration between PUSKAPA and the Indonesian Ministry of National Development Planning (Bappenas), with the Australian government’s support through the KOMPAK (Governance for Growth) program. Previous related studies were carried out with support from AIPJ (Indonesia-Australia Partnership for Justice).