With an enormous fanfare, pomp and ceremony, a consortium of billionaires released their newest space plans: to mine an asteroid. These guys have a history of game changing when it comes to space, having been part of the pioneering of space tourism. Despite the grand expense, the far-fetched nature of the beast and the fact that we’re not even sure what asteroids are actually made of, you kind of think they might actually do it.

The idea of mining other bodies in the solar system for their mineral wealth is not particularly new. The Earth is currently in the grips of a shortage of Helium (yes party balloons may soon be a thing of the past). The moon has itself been touted as a possible source for mining this light gas, in order to keep MRI scanners and the hope of fusion reactors alive.

Putting the ethics of extra terrestrial mining aside for the moment, at the recent 43rd Lunar and Planetary Science meeting I was struck about how little we actually know about asteroids. ‘Asteroid’ is quite a broad-brush term, but describes an object in orbit around the Sun, which isn’t a planet. It now usually refers to bodies, which are circling within the orbit of Jupiter. There are hundreds of thousands of them, with a massive range of compositions – from metal to rocks and carbon rich organics.

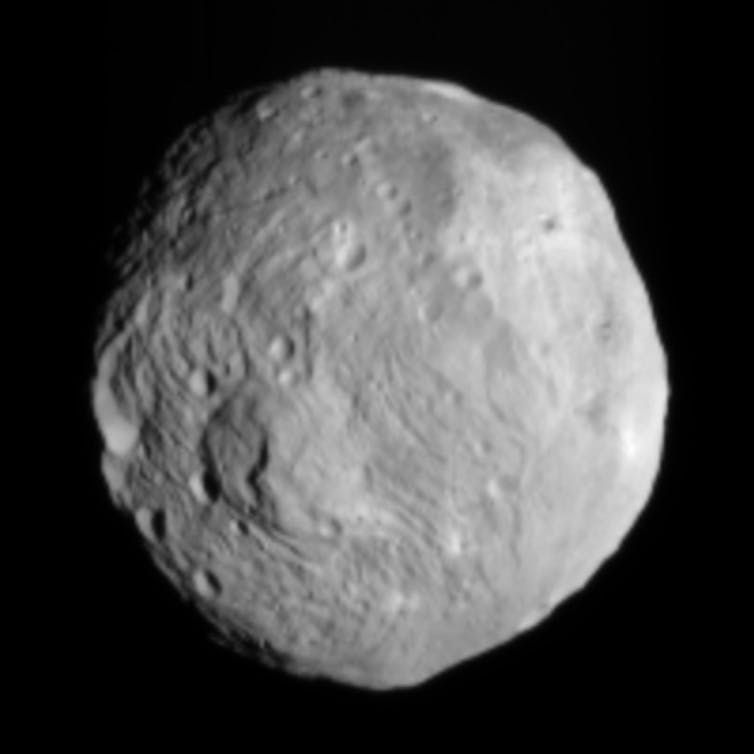

Many of these bodies inhabit the Asteroid belt, a collection of about 90,000 asteroids that live in the space between Mars and Jupiter. NASA’s Dawn mission is currently probing the two biggest asteroids belt objects, Ceres and Vesta. It’s swooping about Vesta has blown apart the fuzzy images we first had from Hubble and revealed the potential for finding water ice as well as rich variety of geological features. It is due to reach Ceres, the biggest asteroid of them all, in 2015.

Mining is one thing but bringing the material back to Earth is, perhaps, the most underestimated challenge. Only very few space missions have achieved this robotically, most relevant was the valiant Japanese Hayabusa mission. It returned dust from the asteroid Itokawa after having trouble picking the stuff up. It plunged back to Earth in June 2010, with the landing guided to the South Australian outback.

One of the main reasons to study these desolate rocks is that many asteroids are protoplanets, leftover mini planets from the throng that came together to form Earth, Venus, Mercury and Mars. They are super old, and detailed knowledge of what they are made of and what they have been through, could reveal much about the formation of our solar system. Will they shown fingerprints from comets passing millions of years ago? How did they survive shattering impacts, and can we learn from these?

Ceres and Vesta, like their many smaller cousins, are yet another marvel of the solar system. They are beautiful and could reveal much about how the Earth was formed, are they really the answer to our resource problems?

So I’d like to throw this open to the floor, am I being too squeamish about the whole idea? Would this drive to space for profit throw us into a new space age?

Or am I right to be a little suspicious, at least uneasy about the feeling that we need to head to space solely to exploit resources because we’re using up those here on Earth?