In February 2016, the conservative American magazine the Weekly Standard had as its cover an image of Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump perched on the top of Trump Tower with a crushed plane in one hand and Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton in the other. The caption read, “King Trump”.

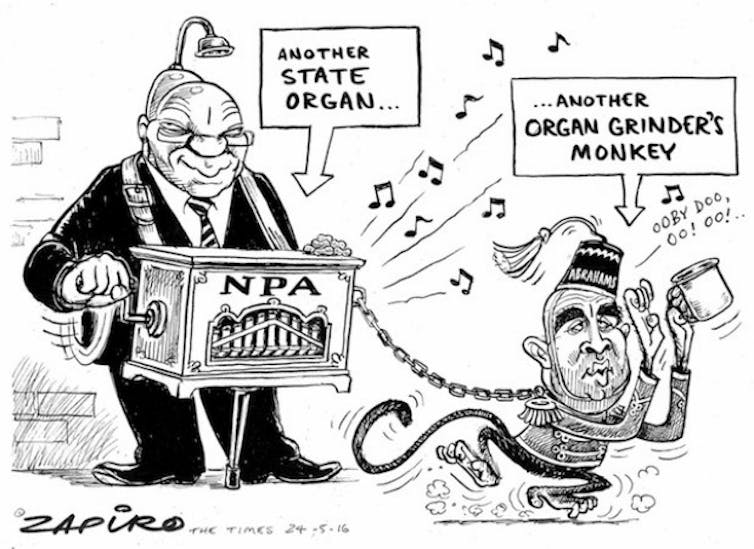

In May 2016, South African cartoonist Jonathan Shapiro, better known as Zapiro, published a cartoon depicting National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) head Shaun Abrahams as a monkey dancing to the tune of an organ grinder, played by President Jacob Zuma. This was after Abrahams announced that the NPA was going to appeal a decision by a full bench of the High Court in Pretoria that found the NPA had made a mistake in April 2009 in withdrawing 783 charges of fraud, corruption and money-laundering against Zuma.

In each case, a public figure is depicted as a primate – the one destroying New York, and the other seeming to be a lackey for his master. Nowhere, as far as I can tell, has there been any outrage about the “simianisation” of Trump, yet Zapiro has come in for some serious criticism and has apologised publicly for his “mistake”. The difference then seems to lie in the fact that Trump is white and Abrahams is black.

Social commentator

This certainly seems to be the view of social commentator Eusebius McKaiser who responded to the Zapiro cartoon thus:

The cartoon is not written or depicted for a society in pre-slavery, white homogenous, mid-West America. He knows his context; he prides himself on his anti-apartheid credentials that he cites regularly.

So context matters … or does it? And when does a public figure’s depiction in the media become hate speech? It is instructive to re-look how the South Gauteng High Court in Johannesburg dealt in 2010 with what constitutes “hate speech”. The right-wing white lobby group AfriForum sought that politician Julius Malema, who was then the president of the African National Congress Youth League, be interdicted and restrained from publicly uttering words, or singing any songs that could reasonably be construed or understood as being capable of instigating violence. The complaint arose from Malema’s use of the well-known struggle song, “Dubul’Ibhunu” – translated, it means “kill the farmer”.

The court specifically excluded context, stating that “the true yardstick of hate speech is neither the historical significance thereof nor the context within which the words are uttered, but the effect of the words, objectively considered, on those directly affected or targeted thereby”. South Africa’s Equality Court declared the song hate speech in 2011.

Cartoon was a mistake

Zapiro himself has described the cartoon as a “mistake”. He writes:

I think it’s very much part of what cartoonists do and satirists do to have that licence to offend and even sometimes to push the boundaries beyond those that society often thinks of and really offend and take things further.

So a mistake – yes. Offensive – yes. Hate speech – really?

As legal academic Ryan Haigh pointed out in an article in 2006, there is a “tenuous balance” to be “struck between promoting rights and limiting freedoms. South Africa’s attempts to criminalise hate speech in an effort to rise above the inequities endured under the apartheid regime exemplify this difficulty.”

Haigh’s position is clear from the title of his article, which was published in the Global Studies Law Review: “South Africa’s Criminalisation of ‘Hurtful’ Comments: When the Protection of Human Dignity and Equality Transforms into the Destruction of Freedom of Expression”. He specifically uses the phrase “hurtful comments” as opposed to hate speech because he wants to challenge the clause in the Equality Act that excludes “the intention to be hurtful” from the constitutional protection of free speech in South Africa.

A puppet, a tool, a lackey

Did Zapiro intend to hurt? Absolutely. But his point was about the head of the NPA being a puppet, a tool, a lackey of the president. It was not about race (it is not clear what “race” the monkey in the cartoon is), but about the fact that both Zuma and the NPA are challenging a court ruling regarding his corruption charges being reinstated.

Writing in a different context – around religious hate speech – constitutional expert Pierre de Vos objected to the provision in the Equality Act that prohibits speech that can reasonably be construed as having the intention to be hurtful. He said it has led to people having a “tendency wrongly to invoke the hate speech provision in the Equality Act whenever somebody they do not like (or who they fear) says nasty things about them or about the group they belong to”.

I think he’s right and it applies here too. It’s a good tactic – we’re all focusing on Zapiro’s supposed racism rather than on the issue to which he was drawing our attention. NPA 1, Zapiro 0.

Hate speech is – or should be – about harm. Trump calling Mexicans rapists and Muslims terrorists is harmful: almost every rally he holds is characterised by violence between his supporters and his detractors. Yes, his utterances are protected under the US’s First Amendment. Some claim that there is in fact a “hate speech exception” but that this is limited to the use of face-to-face “fighting words” generally expressed to incite violence. Other commentators argue that US law does not even have a definition for hate speech.

Harm and offence

I’m not black so I can’t and won’t claim to know how black people feel. But as a woman and a member of a minority religious group, I too have had my share of hurtful comments tossed at me.

Legally and philosophically, we tend to distinguish between harm and offence – the former is considered much more significant and worthy of prohibition, the latter not so much. The same applies to the distinction between harm and hurt: it is argued that acts that hurt is too broad a category to restrict and doing so leads to unwanted – and unwarranted – reductions in freedom.

Ultimately, restriction of speech that does not incite violence and does not intend to cause harm is a restriction too far. It is a small step from restriction of hate speech to restriction of criticism and disagreement. We surely cannot make laws that prohibit criticism or disagreement.