The government will no longer refund 30% of the cost of the loading paid by people who take out private health insurance after the age of 30.

The removal of the rebate from the lifetime health cover loading, once again, raises questions about the efficiency and equity of public subsidies for private health insurance.

This is not the first cut to government rebates for private health insurance. From July 2012, the tax rebate for private health insurance has been means tested. Individuals with incomes below $84,000 now receive a 30% rebate, and the subsidy gradually reduces to zero for incomes greater than $124,000.

And from today, the loading paid by people over the age of 30 who are insuring for the first time no longer attracts a government rebate.

What do the rebates mean?

The private health insurance rebate has been growing at over 6% per year and is estimated to be around $5.56 billion in 2012–13. This is a significant proportion of the health budget that could, for example, cover a national dental scheme, or over a third of the cost of the National Disability Insurance Scheme or could be used to reduce the waiting list in public hospitals.

The main argument for the rebate is that it sustains a viable health insurance industry in Australia. In turn, private health insurance ostensibly supports private hospitals and increased patient choice, and reduces waiting times for elective surgery in public hospitals.

But does the rebate actually sustain private insurance?

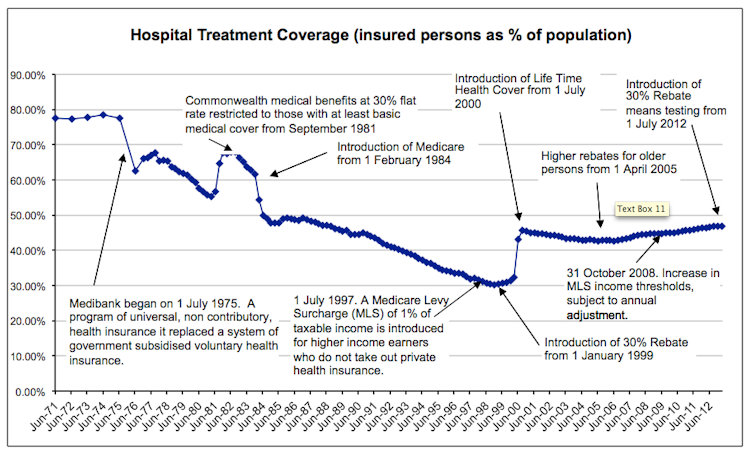

After the 1975 introduction of a universal public health scheme (now known as Medicare), it was expected that private health insurance membership would decline. And that’s exactly what happened.

The graph above shows that private health insurance membership declined sharply, from nearly 80% to just over 30% by the late 1990s.

In response, the then-Liberal government (with John Howard at the helm) introduced a suite of measures to encourage private health insurance membership. These included:

a government-funded rebate on private health insurance premiums,

a means-tested tax penalty for those without insurance,

a premium surcharge for people taking out membership after the age of 30, and

a prominently advertised “Run for Cover” scheme that waived the surcharge for those taking out insurance before June 30 2000.

These threats of higher premiums, coupled with the “Run for Cover” campaign, were the main drivers of the jump in membership from 30% to 45% in 2000. Membership levels have remained steady since then.

It’s too early to tell if the means-testing of the private health insurance rebate will have an impact on membership levels but, so far, it has not. That is, people don’t seem to have stopped their private health insurance because they no longer receive funding from the government for it.

In fact, membership seems to have increased by more than 1% between July 2012 (when means testing was introduced) and March 2013.

But while membership went up in the aftermath of the Howard government drive, it’s not clear that subsidising private insurance from 1999 was successful in reducing pressure on public hospitals – its main expressed intention at the time.

Funding the rich?

New insurees who responded to the financial incentives did not significantly reduce their use of the public hospital system. Waiting times in public hospitals did not fall when private insurance take up increased and national median waiting times rose in the subsequent decade.

Some people who would have been treated in public hospitals shifted to private beds, but the resources went with them. The result was no significant overall increase in treated patients.

Indeed, since government still paid for public hospitals, and now paid a rebate on private insurance for treatment in less efficient private hospitals the net effect was to increase government expenditure

At best, there may have been some short-term saving in direct government spending from increased membership, but that was offset by patients paying out-of-pocket costs, or in premiums. In this context, premiums are like a tax but without the variation with income - private insurance “reshuffles money and reshuffles the queues”.

Private health insurance and access to private hospitals are the main reasons why people who are better off wait less time for surgery. What has actually happened is that Medicare’s equity-of-access principle has been eroded by a tax subsidy of over $5 billion for the financially better off to jump the queue for elective surgery (and to use more dental or optometry services).

Our tax dollars would be better and more equitably spent on prevention, improving hospital services, and widening access to other services.

Why have private health insurance at all?

Even without the government subsidy, there remains the question of why we want to a parallel private health system for the quality of health service that we agree should be available to everyone paid from their taxes under Medicare.

Private insurance premiums are a cost to individuals just like taxation. And they cost more than a tax-funded system without producing better quality health outcomes. Medicare has advantages of scale (it is accessed by everyone) and purchasing power that enable lower costs and improved quality control.

In contrast, private health insurance is generally unsuited to pooling resources across people of different health needs and income, while actively ensuring equity of adequate care. This is especially so in Australia where insurance companies have regulated premiums and very limited scope to tie member contributions to their insured risk.

If we want high quality health care with choice, private insurance is not the only way we can have it – and is relatively expensive. Private hospitals could be subsidised from taxes at lower cost to the public budget.

More importantly, reducing the number of health funders increases the potential for better and more efficient health outcomes by integrating health-care provision – a feature that is sorely lacking in our fractured health-care system.