Were The Guardian Australia and the ABC ethically justified in publishing leaked classified material showing Australia tapped the telephones of Indonesian president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, his wife, and senior Cabinet ministers?

It is an acutely difficult question. Usually decisions about disclosure of previously secret or confidential information requires journalists to weigh the public interest in disclosure against the foreseeable harm that is likely to follow. The greater the likely harm, the higher the public interest threshold needs to be.

In this case, however, there are at least four public interests, some of them in conflict with others:

-

Having an intelligence service that is effective in protecting Australia’s national interests

Maintaining sufficient secrecy to enable that function to be achieved

Seeing that the intelligence services are accountable for their performance, and

Enabling Australia to conduct effective diplomatic relationships with other countries.

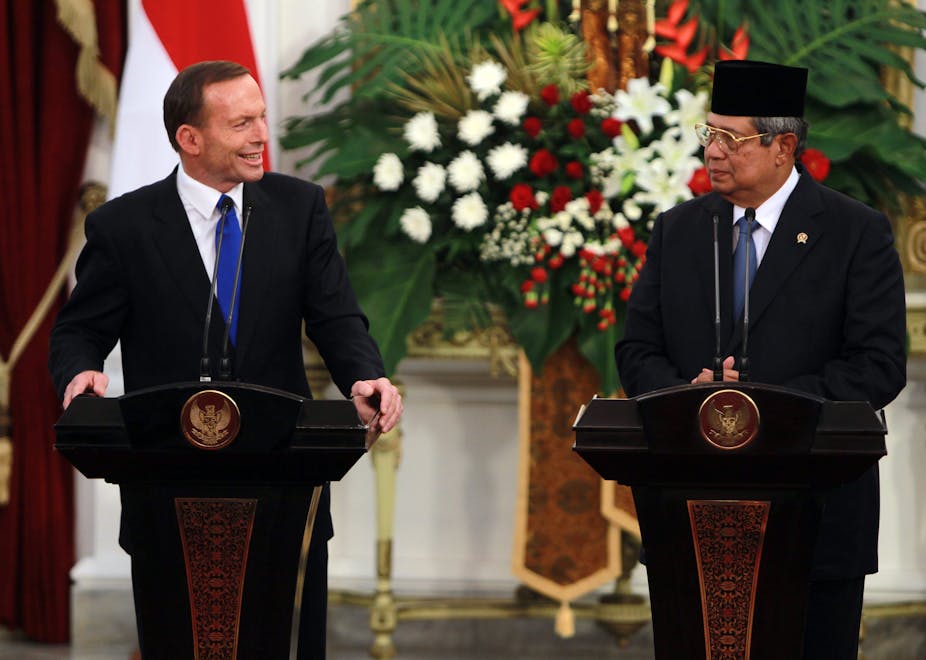

The foreseeable harm that would result from the revelations about the phone tapping is exactly what is now occurring. A serious diplomatic row has erupted between Australia and its biggest neighbour, Indonesia - a country with whom Australia’s relationship has been delicate for decades, and whose co-operation is critical in deterring people smuggling and drug trafficking, among other policy priorities.

This is significant harm. Is the public interest in disclosure commensurate with the harm done?

We have only limited information from The Guardian Australia and the ABC about their reasoning. However, it is obvious that they attached a higher priority to the public interest in the accountability of the intelligence services than to the other three competing public interests.

Behind this lay a value judgement. The ABC’s managing director Mark Scott indicated in answer to questions at a Senate estimates committee hearing on Tuesday what this was. He compared the telephone tapping by Australia’s Defence Signals Directorate (DSD) to the gross moral wrong involved in the Australian Wheat Board’s bribing of officials in return for purchasing Australian wheat.

Whether the moral wrong amounts to criminality in the DSD case is an open question. Experts in international law have been reported as saying that espionage activities exist at the point where international law gives out.

However, once a journalist or editor has made a judgement that they are in possession of evidence showing gross moral wrongdoing by public officials, they then must confront the question of what to do with it. To publish, or not to publish? This is the point at which the concept of censorship becomes relevant.

In journalism, the question of censorship usually centres on motive: why am I not publishing? There are sometimes good reasons not to publish: to protect the safety of soldiers in war or to respect a person’s right to a fair trial, for instance. There are also bad reasons not to publish: to avoid embarrassing the government or an advertiser or a valued source of information. It is the “bad” reasons that amount to censorship.

From what we know, it seems the chain of reasoning by The Guardian Australia and the ABC went like this: we have evidence of gross wrongdoing by the DSD. If we publish, we will cause great embarrassment to the government; we are likely to cause serious tensions between Australia and Indonesia; and we might damage the capacity of the DSD to gather intelligence in Indonesia - at least for the time being. However, we believe that the public interest in holding the DSD to account trumps these competing public interests because of the gravity of the wrongdoing.

Competent journalists of goodwill might come to a different conclusion. They might prioritise the public interests differently and strike the balance between benefit and harm in a different place. But this does not make the actions of The Guardian Australia and the ABC wrong. Their case to publish is a defensible one, based on what we know at the moment.

They would strengthen their position by supplying the public with a fuller account of how they came to that decision. Sunlight, as they say, is a great disinfectant. And for former foreign minister Alexander Downer and others impugning their motives (including fellow journalists Andrew Bolt and Miranda Devine), disinfectant would help.

Downer’s rather partisan contribution – where he made a point of characterising The Guardian as “left-wing” – was that the media outlets had released the information now in order to sabotage the Abbott government’s attempts to enlist Indonesian help in dealing with asylum seekers. This assertion seems to be based on hearsay.

The two media outlets have responded by saying that while The Guardian in England had had the material since receiving it from the former US intelligence contractor Edward Snowden in May, it had taken time to sift this material out of the vast Snowden tranche. They said they had received the material in Australia only a few days before publishing, and in the meantime had taken steps to redact certain content and to conduct other checks.

However, in a case where accountability is a central issue, transparency of process by the media would set a useful example.