The quest to identify the bones of Miguel de Cervantes looked bleak in the summer of 2014. “We’re not going to find Cervantes with a nameplate on his coffin,” the project’s forensic director, Francisco Etxeberria, wryly predicted in an interview with Spain’s Agencia EFE in June. But his name on a coffin is not a far cry from what has, in fact, now come to light in Madrid. For researchers have announced that they have found the tomb of Spain’s most famous author, almost 400 years after his death.

In recent months, tantalising clues have emerged from the crypt where the author of Don Quixote was interred in April 1616. The research team first used ground-penetrating radar to locate some 36 burial cavities in the walls and floors of the Trinitarian Convent Church. These graves yielded bones, wood, and textile fragments, and mass spectrometry dated the detritus to the early 17th century.

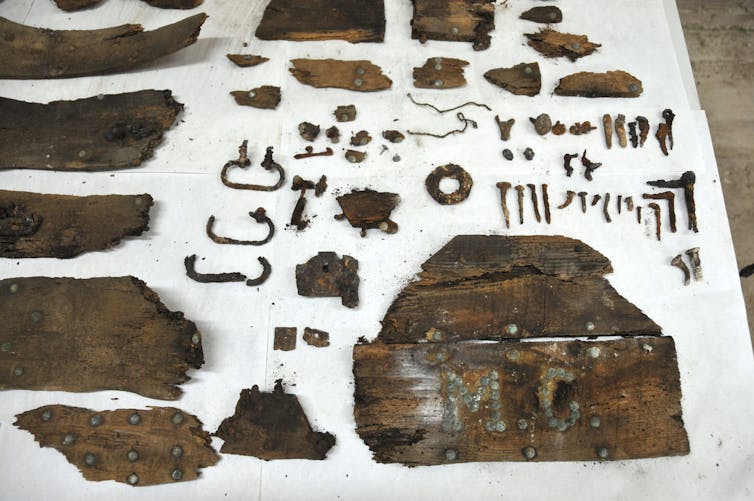

Most remarkable of all, the excavations unearthed remnants of a crumbling coffin, one of its boards bearing the initials M C in a constellation of nail heads. They now believe that this is the final resting place of Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra.

The answer was not as straightforward as a nameplate: various historical sources indicated that he was buried in the grounds of the Trinitarian Convent, but refurbishments on the site had obscured any trace of the precise location. The niche that contained the auspicious initials also held a jumble of skeletal remains, including those of various children and a woman, possibly the author’s wife Catalina de Salazar. Further tests, such as DNA comparisons with known relatives, could provide some clarification as to whose bones are whose.

If the forensic and documentary evidence proves conclusive, Madrid has floated plans to reinter the bones, mark the occasion with a special ceremony, install a new plaque at the site, and construct a new public entrance to the crypt — all in time for the 400th anniversary of Cervantes’s death.

Aside from a pretext for public spectacle, what is the point of this grave-digging? As I have argued before, exhuming the mortal remains of Spain’s greatest author will contribute little, if anything, to our knowledge of the man or his work. At most, it has confirmed the location of his grave, which was never seriously in dispute. We have always known that Cervantes was buried in the Convent’s crypt, even if we could not point to a particular tombstone.

But the search for the author’s bones is not an empty exercise; nor is it merely a lure for tourism. Such commemorations do have wider cultural value. They ignite public attention, inspire re-readings, and invest an all-but-forgotten corner of the city with a renewed, imaginative depth. In preserving cultural heritage, literary commemorations also preserve the dignity of those whose lives are connected to that site.

As an illustration of what I mean, consider the following anecdote from the Peninsular War.

When Napoleon’s troops invaded and occupied Spain, they marched through El Toboso, renowned as the home of Don Quixote’s idealised lady-love, Dulcinea. On that occasion in 1809, the town’s literary fame spared it the depredations of war. Rather than lay waste, the soldiers passed through with an exchange of witty remarks and respect. “Voilà Dulcinée!” the troops saluted women who peered from the windows. “The pleasant jests about Dulcinea and Don Quixote,” one member of the French forces reported, “formed a common bond between our soldiers and the citizens of El Toboso. The French treated their hosts with kindness.”

Cervantes’s fiction, ironically, enabled the invaders to perceive the real life townspeople as worthy of goodwill.

If the militants currently pulverising ancient artefacts in Mesopotamia had read more Gilgamesh and fewer fatwas, they might be more inclined to recognise humanity in the region they are ravaging, more inclined to perceive shared emotions in the people whose history they are obliterating.

Literature humanises and sensitises. Through it, we cultivate our capacity to perceive potential and transcendence in others; through it, we can imagine our surroundings enriched with stories and histories. This is the imaginative, perceptive capacity that Cervantes celebrated in his greatest novel. The quixotic imagination can see a princess in a peasant girl, a valiant squire in a neighbouring swineherd, and, yes, a genius of world literature under the flagstones of a parish church.