We’re a month out from the latest episode of mass casualty violence in Toronto, and the city is still grappling with the impact of the shooting that left two dead in the bustling area of the city known as The Danforth.

The shooting came just three months after the van attack that killed 10 people in Toronto’s north end, traumatizing a city unaccustomed to such acts of mass violence.

In the first four weeks after the July 22 mass shooting, events included two funerals, a benefit concert, community vigils and the creation of temporary memorials along The Danforth.

As an expert in disaster and emergency management at York University, not far from where the latest attack occurred, I’ve been making detailed observations at the scene in order to both document and understand the first month of this newest disaster recovery for Toronto — a city that is unfortunately becoming too well-versed in mass casualty disasters.

Public mass shooting

Danforth Avenue was the site of the shootings in Toronto’s Greektown neighbourhood. It’s an area of the city known for its vibrant public spaces and busy patio culture.

The motives of the deceased shooter remain unknown as the investigation proceeds. But we do know that for some reason he targeted one of the city’s most high-profile neighbourhoods, symbolic of Toronto’s summertime festival culture.

Like the van attack, terrorism came to mind as a possible cause in the immediate aftermath of the violence. After the shooting, ISIL (Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) issued a communique claiming responsibility for the event, but authorities indicated the claim doesn’t match what their investigation has uncovered.

The shooting on The Danforth is best defined as a public mass shooting. These incidents occur in relatively public places, usually involving four or more deaths, and a gunman who somewhat indiscriminately selects victims. A public mass shooter’s agenda stems from their specific personal experiences and psychological conditions, not broader socio-political objectives.

The initial response

Like the van attack, the mass shooting resulted in a large crime scene with multiple deaths and injuries at different locations. The rampage occurred along a 400-metre stretch of Danforth Ave. and involved sites ranging from a public parkette to individual businesses.

At the time of the incident — approximately 10 p.m. on a Sunday evening — it was initially difficult for those in the middle of the mayhem to identify the type of crisis that was occurring around them. A roving gunman randomly targeting people was completely unexpected in that setting.

Immediate civilian responses included rapid first-aid provision to the wounded, followed by actions to evade the gunfire, including evacuation, sheltering in place and lockdowns. Out of necessity, ordinary bystanders improvised lifesaving medical assistance until first responders converged on the scene within minutes. Some of the bystanders acted heroically and sustained injury as they attempted to save others.

A 10-year-old girl and an 18-year-old woman died from their wounds, and 13 people were hospitalized with various prognoses for physical recovery.

The shooter, identified as a 29-year-old man, died from a self-inflicted wound when confronted by police. As in the van attack, hundreds of people on the street were directly exposed to trauma by witnessing the carnage.

Organizing recovery

The disaster response efforts obviously began immediately following the shooting. Police response protocols relating to gun violence incidents transitioned to first responder actions to manage mass casualties. These immediate actions were followed by subsequent crime scene investigation and cleanup, all of it taking place within hours.

Given the multiple urban functions (recreation, retail, residential and transportation) of Danforth Avenue, it was necessary for normalcy to return to the street quickly.

In the week after the shooting, one business, a popular dessert café where one of the casualties occurred, remained boarded up, though it has since reopened. Other businesses that were impacted quickly repaired bullet holes, erased remnants of the violence and resumed business as usual.

While the physical recovery of the neighbourhood was accomplished in short order, social recovery will take much longer as the neighbourhood comes to terms with what it means to be the site of a public mass shooting.

Read more: Violence in Toronto: How support can help prevent PTSD

One of the ways that the Danforth is coming to terms with the public mass shooting is via memorials. Residents of the Danforth, businesses in the neighbourhood, the local business improvement association and churches worked quickly to reclaim the streets after the violent attack. An evening vigil held three days after the attack was one of the first public events. Temporary improvised memorials to the victims also materialized.

The main site of grieving was a city-owned parkette, the focal point of Greektown. At the Alexander the Great Parkette, a memorial grew around an existing fountain and garden.

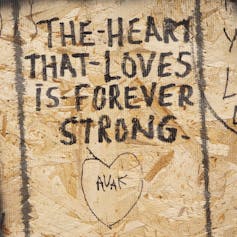

In addition, two sidewalk memorials also emerged, and the temporarily boarded-up dessert café became a collection point for items of grief expression. At a third site, in proximity but not directly related to the tragedy itself, the blank plywood boards of construction barricades provided a canvas for mourners to memorialize the dead.

After the van attack uptown from The Danforth, a temporary disaster memorial was in place for 40 days before being completely dismantled. On The Danforth, makeshift memorials were relocated due to the annual Taste of The Danforth festival. The event is one of Canada’s largest street fairs with an estimated 1.6 million people in attendance.

The long-term fate of the disaster memorials will involve a balancing act between the need to remember and the need to move forward.

Looking ahead at a new normal

Following the van attack, I suggested that there was a new normal in place for Toronto and I posed the question: What can we expect in the weeks and months ahead and beyond?

Read more: How Toronto is recovering from the van attack

The answer to that question is now becoming clear: The greatest strengths of Canada’s largest city also represent significant weaknesses.

One of the factors that makes Toronto a desirable place to live, work and visit is neighbourhoods like The Danforth. The open, active public life at street level provides for many opportunities ranging from creativity hubs to opportunities for social and cultural diversity and the promotion of active local economies.

But those neighbourhoods also represent “soft targets” to exploit by people driven by antisocial and violent motives. These are places that are by their nature open access, not well-defended — and security posture is not top of mind.

The question now is: How does Toronto maintain its active and bustling neighbourhoods while also defending itself?