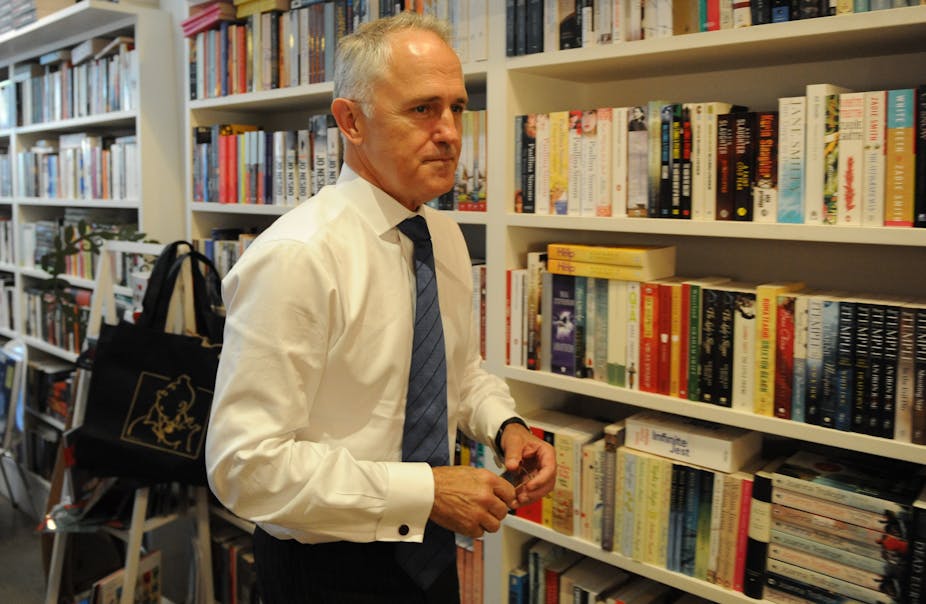

Malcolm Turnbull, Federal Shadow Minister for Communications and Broadband, last night gave a lecture about the financially imperilled newspaper industry, speaking about how time and staffing pressures lead towards shriller and shallower coverage. The speech, “The future of newspapers: is it the end of journalism?”, was delivered at Melbourne University’s Advanced Centre of Journalism, and a transcript appears below.

Malcolm Turnbull, Federal Shadow Minister for Communications and Broadband

Thirty three years ago, when I joined the news room of the London Sunday Times, its editor, Harry Evans, gave me “Editing and Design” a five volume manual of English typography and layout.

He inscribed them “To Malcolm, with a warm welcome to the grubby ranks of the hot-metal men. Harry”

Re-reading those volumes today, it is remarkable how much is as relevant today as it was in the 1970s. Good design, clear expression, accurate and engaging reporting – the objectives are the same, only the context has changed.

And that perhaps should be the theme of my remarks tonight. We lament the death of many newspapers and the loss of thousands of journalists’ jobs.

But just as the craft of the journalist is as enduring and important regardless of the medium by which it is practised – print, radio, television and now the whole converging digital domain – so too is the importance of journalism, honest and ethical, fearless and independent, responsible and accurate journalism; for without it we will struggle to remain a free society, struggle indeed to remain a democracy.

I had come to London in 1978 with a bit of a reputation as a journalist and debater to study at Oxford on a Rhodes Scholarship.

During my time at Sydney University I had managed to fit in a busy life as a reporter while completing my Law degree and I thought I might do the same in England.

I had first met Harry Evans a year or so before in the course of a debate at the Cambridge Union in which he was one of the paper speakers. A visiting Australian debater, I spoke lower down the batting order. After my speech a note was passed to me. It had the letterhead of the Sunday Times and on it Harry Evans had written “Good speech. Come and see me in the Grays Inn Road tomorrow.”

Harry Evans was a hero to every young journalist of my generation. At the Sunday Times he had championed investigative journalism, exposed the horrors of thalidomide. He personified the ideals of independent journalism.

The next day Harry offered me a job, and when I said I had to go back to Australia to finish my law degree said “Don’t do that. Think of what awaits you. Law will certainly make you more money than journalism – but where does it end? Chief Justice? Or much worse.” He shivered slightly “You could end up a politician.”

I did go back to Australia and I did finish my law degree and continued working as a reporter and stayed in touch with Harry Evans and by the time I returned to London, no doubt because I was young and cheap, I had an offer to work at the Sunday Times – for my hero – and also at the Observer, edited by Donald Trelford.

At that time the Thomsons, owner of the Sunday Times and Times newspapers, were in trench warfare with the printing unions as they tried to reform the extraordinarily inefficient workpractices which were threatening the financial viability of what should have been a very, very profitable newspaper group.

My head told me I should go to The Observer – there was no pending stoppage there – but my heart allowed me to be persuaded by Harry that everything would be sorted out by next Thursday week (or thereabouts) and so I started at the Grays Inn Road.

It was a weird period – the journalists did a deal with management and stayed on the payroll. The printing unions did not and were locked out. For over a year we wrote stories and prepared papers which were ready to go out when the breakthrough came, as it nearly did every week or so we were told..

Finally, after nearly year a settlement was reached and the papers were back on the street in November 1979 but two years later Murdoch bought Times Newspapers and then proceeded to break the power of print unions through his 1986 move to Wapping and more rational work practices.

The rest of Fleet Street followed and survived to prosper.

As another Australian footnote to that story, while still employed by the Sunday Times and frustrated by the intractable dispute, Kerry Packer and I met with Harry Evans to propose a strategy that was not very different from Wapping.

Kerry would buy the newspapers from the Thomsons on the basis he would then print them in the Grays Inn Road with non-union labor and distribute them by independent truck drivers as in Australia – as opposed to using the union controlled railways. We had worked out strategies to get paper into the country in the face of black ban and had sought legal advice on how to deal with pickets attempting to physically block access in and out of the plant.

The Thomsons were not ready to deal at that time, but it is interesting to speculate on the alternative history if they had been.

Having got off to a good start as a journalist of course my career has been in decline ever since – lawyer, banker, entrepreneur,colourful Sydney business identity and now, as Harry Evans had feared, a politician. What’s next? Too terrible to contemplate.

But along the way I have had a lot to do with the newspaper and media business generally. Working for Kerry Packer including selling and buying back the Nine Network, restructuring and later helping take over John Fairfax, helping restructure the Ten Network from being the third rating and least profitable network to being the third rating and most profitable network. And of course with Sean Howard and my old Bulletin editor Trevor Kennedy founding OzEmail the first big Internet company in Australia.

And naturally as a politician I have an especially keen interest in the media – after all as Lucy has often observed in Canberra the politicians are the foxes and the press gallery the hounds.

There is a media inquiry going on at the moment which was, as we know, set up by the Government with the aim of taking a swipe at News Corporation in the wake of the shocking crimes and misconduct at the News of the World.

The Leveson Inquiry which is the UK’s judicial inquiry into the whole affair is exposing a cynical corruption in the British press that will surprise and shock even those like myself who were brought up on the old ditty:

“Thank God one cannot bribe nor twist The Honest British Journalist For seeing what he does unbribed There is no need to do so.”

But mercifully there does not appear to be any evidence of phone hacking or similar crimes in Australia. I would not be complacent about that – but on the face of it our media seem relatively responsible by comparison.

Which rather begs the question of whether the inquiry, headed by Ray Finkelstein QC, needs to be happening at all. I imagine it will do little harm if not much good.

But while it seems it is spending a lot of time discussing whether the Press Council has sufficient teeth or should be buttressed with Government regulation of the kind that applies to broadcast media – and those who listen to the Sydney shock jocks can attest what a salutary and therapeutic influence the ACMA has on their commitment to accuracy and balance.

It also seems to be considering the iniquities of the concentration of metropolitan daily newspaper ownership in the hands of News Corporation. Whatever the merits of that dispensation, it has been in place since 1986 and the slice of the overall news media pie occupied by daily newspapers is shrinking.

However the big issue, the whale in the bay, which we should be analysing and discussing is the future, the viability of journalism itself. Rather than spending too much time on how many newspapers are owned by Rupert Murdoch, we should be asking whether there will be any newspapers left for him,or anyone else, to own at all.

What sort of democracy, what sort of society will we have if there is no Age, no Herald Sun, no Sydney Morning Herald and no Australian – can the great newspapers which have formed the foundation of newsgathering, reporting and analysis be replaced by a sea of blogs and tweets?

Around the developed world newspaper revenues and profits have plunged. Hundreds have been closed, many more are struggling to survive.

There are so many examples. But consider two of the greatest newspaper groups in the world – Fairfax Group here in Australia and the New York Times Company in the United States. As of last Friday their shares had each lost about 85% of their value from their height about ten years ago.

I don’t need to labour the statistics with you but in a nutshell the picture is like this.

Newspaper circulations have declined in most developed countries. In Australia, with a stronger economy, they have declined by 3% between 2007-2009, in New Zealand the decline is 13%, in the UK 21% and in the USA 30%. And that was of course before the closure of the News of the World.

However the circulation story is rather misleading – most newspapers have more readers now than they have ever had. Their print circulation and readership has declined, markedly in some cases, but their online readership has exploded. The Sydney Morning Herald claims one million readers on the weekend, Neilsen Online records it as having about 3 million monthly unique users as of October.

The problem therefore is not lack of readers, but lack of revenue.

Since 2002 total spending on advertising has grown by 60%. Spending on television has grown 40.5%, spending on newspapers has grown by 19% and spending online has grown a massive 13.5 times.

Another measure is that between 2000 and 2010 the shares of total advertising spend in Australia (excluding search) changed dramatically: newspapers down from 45% to 31% , magazines down from 8% to 6%, television down from 34% to 33% , Radio down from 9% to 8%, Outdoor steady at 4% and Online rose from close to zero to 18%. And if the figures included search as well, the online share would be even greater.

In the United States newspaper ad revenues dropped 47% from 2005 to 2009 and over the same period cut their editorial spending by $1.6 billion a year or 25%. Staff at daily newspapers have shrunk by more than 25% since 2006, television network news staffs and newsmagazine reporting staffs have halved since the late 80s. Is Australia so different, or is this a case of “you ain’t seen nothing yet.”

Traditionally newspapers have divided their advertising into classifieds and display and in Australia classifieds were dominated by the big metropolitan broadsheets in particular The Age and the Sydney Morning Herald which only a decade ago provided nearly 2/3 of their revenues.

Newspaper classifieds have not quite vanished. One newspaper chief executive told me last week they hoped to keep about a quarter of the old classified revenue by diverting it into, albeit low yielding, display advertising. So far this was largely real estate but as the online vehicles for real estate are becoming more and more compelling, it is questionable how long newspapers can hang onto that category.

The problem of course is not simply that the online environment provides another competitive platform for the delivery of news, entertainment, information and advertising, but that online is a far more efficient and cost effective means of delivering any advertising which could be described as demand fulfilment (ie enabling you to find something you are looking for such as a flat, a car, a job) as opposed to demand creation (ie promoting brands, products in a manner designed to attract and engage the attention of the reader).

Analytically one could say that in advertising for demand fulfilment online search simply kills any printed classifieds section or directory publication.

And so in that regard it doesn’t really matter whether newspapers’ readerships are up or down – the Internet simply offers a better mousetrap for what had been a very, very large part of newspapers’ advertising base – so large and so secure that they used to be called “the rivers of gold”.

Rupert Murdoch once observed that the Internet will destroy more profitable businesses than it will create and he was certainly right at least so far as his empire is concerned.

Closer to home, the value created for the shareholders of Seek or REA Group, for example, appears to be (especially on an earnings base) much less than the value lost to the digital world by the shareholders of Fairfax.

Newspapers created a platform for advertisers by producing sufficiently interesting content to attract a large mass of readers. That content is very costly to produce. Television and radio, in somewhat different ways, do the same thing.

So it is galling that the two current giants of the online world – Google and Facebook – create very little content of their own. Google is above all a search engine and an aggregator of other people’s content and a provider of its own applications and services. It produces very little content, and certainly no journalism, of its own. Facebook which has 800 million subscribers who use it at least once a month produces no content of its own; its users do that. Ken Doctor of Newsonomics has estimated that 63% of online digitial advertising revenue in the US goes to these aggregators and search engines – including Google, Facebook, Yahoo, AOL, Microsoft.

In the US, Pew’s 2011 State of the News Media finds that online advertising revenue has now surpassed that of printed newspapers. Search alone, dominated by Google and Yahoo, attracts 48% of all online advertising.

Does the algorithm trump journalism?

I have not been able to find any authoritative numbers for the Australian scene, but the chief executive of one of the leading online platforms told me recently that Google so dominated the Australian market its revenues were five times that of its nearest competitors including Yahoo7, Fairfax or NineMSN.

Neilsen Online’s latest unique audience numbers for Australian sites in October 2011 are dominated by Google with 14 million, Facebook and NineMSN with 11 million, at number 13 ABC Online with 3.5 million and at 20, the SMH with 3 million. In the top 20 Australian sites by that measure only the ABC and SMH have a substantial investment, and Yahoo7 and NineMSN a somewhat lesser, investment in journalism

It does all seem very unfair.

As the Pew survey concludes:

“..most in the news industry have come to accept a daunting reality: Advertising in online spaces will probably never generate the sums – or at least the profits – that advertising generated in traditional platforms like printed newspapers. To survive financially, the consensus on the business side of news operations is that news sites not only need to make their advertising smarter, but they also need to find some way to charge for content and to invent new revenue streams other than display advertising and subscriptions.”

In the United States from 2005 to 2009 newspapers’ sites traffic doubled to 3 billion page views. Online advertising revenue for those newspapers grew by $716 million, but print advertising lost $22.6 billion. Hence the bitter observation “print dollars are being replaced by digital dimes.”

Newspapers are busily experimenting with different models. Traditionally, and I suspect in hindsight very mistakenly, online news was free. And once given free access readers felt it was their entitlement.

There are at least two big questions here. Will enough readers pay enough money to view online news to offset the loss of advertising revenues from the printed medium? What is the best paywall model that will hit the sweetspot of subscription revenue and at the same time ensure there are enough readers to maintain advertising yields.

The jury is out on both, but I will venture some early observations about what seems to me to be working and what is not.

Financial newspapers, pre-eminently the FT and the Wall Street Journal, have an enormous advantage. The business community is used to paying for financial news and information and it is no surprise both papers are doing well in terms of their online only subscriptions.

In terms of general newspapers the most successful so far appears to be the New York Times which as at October had 360,000 digital subscribers. The New York Times offers a “freemium” model whereby readers can access up to (currently) 20 articles a month for free after which they have to subscribe. The FT has a similar approach.

The advantage of the freemium model is that the paper’s articles can be linked in search engines and above all social media like twitter and facebook. On the other hand the Times of London approach which is an impermeable pay wall prevents that kind of linking. The consequence is that the newspaper becomes effectively invisible in the online world other than to its handful of paid subscribers.

The freemium and other models will continue to be tweaked, but it seems that it is the better approach – at least so far.

The arrival of the tablet and smart phones offer what will become for most people their principal device for viewing digital content. Apps offer the ability to provide a very compelling and magazine-like, reading experience – the Economist app for example is eerily close to the experience of reading the magazine.

However while the tablets offer the opportunity to provide a better digital format, they also potentially provide even more competition with the printed newspaper because they enable us to read online news in settings which had been less amenable to a computer and thus had remained the preserve of print – the train, the bus, on the couch or in bed.

So what does this brave new world mean for journalism?

Not that the thousands enrolled in journalism and media courses seem to have noticed, but self evidently fewer newspaper journalists. Whichever way you look at it, newsrooms are shrinking if not closing.

The Canberra Press Gallery for example has gone from 283 journalists in 1990 to 190 today. A decade ago the Sydney Morning Herald and Sun Herald had an editorial staff of 500 – now it is less than 300. The Age’s newsroom has shrunk by ¼ over the last five years.

I will spare you more grim statistics in the same vein, but the short and obvious point is that as newspapers’ profits dwindle, if not disappear, so does their capacity to employ journalists.

Now it is easy to be sentimental about the decline of newspapers, but tonight I want to reflect on the way these changes to the news business are impacting on both the quality of journalism and of our democracy.

The first point to make is that the decline in newspapers goes right to the very heart of the news industry. As those of us who have worked in the electronic media know very well, the newspapers traditionally have provided the news foundation which the rest of the media have built on and, more often than not, simply re-run.

The reason for that of course was that newspapers had both the space to cover the widest range of news and the staff to do it.

Because most broadcast news has much less capacity, a smaller news hole you could say, its journalistic resources have also been smaller and more targeted than newspapers. The emerging exception to this is the ABC of which I will speak a little later.

The consequence of this decline in journalism is that too many important matters of public interest are either not covered at all or covered superficially. At the local level, there is less attention paid to local councils and even state parliaments.

There hasn’t been a thorough analysis of this decline in Australia, but in the United States there is a growing alarm at the loss of more than 13,000 newspaper newsroom jobs in the last four years and the dramatic declines in political reporters, at every level, as well as declines in reporters with special beats such as health, education and environment.

Now this raises real risks for democracy. Her Majesty’s Loyal Opposition does its best with very limited resources, but more often than not the most effective means of holding a government to account is through a vigorous and independent media. During the last, appalling, term of the NSW Labor Government the most rigorous and consistent criticism came from the Sydney Morning Herald and the Daily Telegraph. This is not to take anything away from Barry O’Farrell’s opposition, but any critique offered by an Opposition is always viewed with skepticism by the public – “they would say that wouldn’t they.”

The most effective check and balance on government has been an independent press which maintains its credibility by ensuring that its criticism is balanced and based on fact – based indeed on solid journalistic work. And that is the risk of excessive partisanship or bias – the less objective, the more shrill a paper or a broadcaster or a journalist appears, the less credibility they have.

Another consequence of this decline in newspapers is that journalists have less time to do the hard, time consuming slog of researching and investigating stories in the way they did before. Those newspapers like The Age here in Melbourne that remain committed to investigative journalism know it comes at a high cost and that its greatest threat is not a writ for libel but the company accountant.

Consider the shrinking Canberra Press Gallery – the vast bulk of its coverage of federal politics is now about personalities and the game of politics.

Readers seeking a better understanding of how the carbon tax or the mining tax, for example, will operate will often struggle to find much assistance in the output of the gallery – with some very honourable exceptions - compared to the millions of words written about Kevin Rudd vs Julia Gillard let alone Tony Abbott’s budgie smugglers.

There is a reason for this. You can knock out a piece on the personalities of politics in a few minutes – a couple of phone calls to the usual anonymous sources for some party room gossip and away you go. But in the midst of all the blasts and counterblasts from vested interests pro and con about the mining tax where is there the rigorous analysis that cuts through the inevitably exaggerated claims of both sides. I am sure someone will point me to a few examples, but they would have been hard to find.

The consequence of all of this has been that what we used to call the 24 hour news cycle has become instead an opinion cycle.

Certainly declining revenues have contributed to this. Research and reporting, especially investigative reporting is expensive. Opinion on the other hand is cheap and given most people do not go into journalism (any more than they go into politics) because they are shy and retiring, having a column of your own in which to pontificate carries far more status and weight than actually reporting the news or explaining the latest legislation or policy debate.

But there is another and potentially more troubling factor that is leading to this substitution for opinion for news.

Over the last few decades we have seen a proliferation of mediums through which news and information can be viewed. In my youth as a reporter we were limited to the newspapers (more then than now), a few television stations, a few more radio stations and a handful of magazines.

In terms of reaching mass audiences for news the most influential media were the big papers and the television stations. Newsmagazines (apologies to my old alma mater The Bulletin) were never a big deal in Australia.

And because their business depended on them reaching a mass audience, they had to strive to achieve some kind of breadth and balance that could accommodate a wide range of readers with a wide range of views and interests. As Arthur Miller said , a good newspaper is a “nation talking to itself”.

However, while newspapers and magazines have declined the various electronic media have exploded; first radio stations, then cable television and now the Internet with an almost infinite range of platforms catering for every interest or opinion.

And the consequence has been that very often the most successful media business model is no longer to be the nation talking to itself with all of the diversity that implies, but rather a narrow section of the nation talking to itself.

The proliferation of outlets that digital technology has enabled has itself contributed to the changing nature of what we regard as ‘news’ and the way in which many citizens perceive politics. As the late Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a Democrat Senator for New York for 24 years said “Everyone is entitled to their own opinions, but they are not entitled to their own facts.”

In the era when much of society shared the common ground of the news bulletins on three or four great broadcast networks, this was true. But today, if we think about the US, liberals can get the ‘facts’ (as well as the opinions) they want from MSNBC, conservatives can do likewise from Fox News, and the voters in the middle can tune in to CNN. Not only will each obtain the opinions they want to hear – the offering of which has turned out to be a vastly profitable commercial opportunity – but also, increasingly the ‘facts’ that support their preconceptions.

Little wonder that Stephen Colbert, the host of the humorous conservative TV show on Comedy Central, has satirised ‘truthiness’ a fact that someone claims to know intuitively without regard to evidence, logic or the objective facts.[9] We are not yet to the point in Australia where those on different sides of any given issue have completely different understandings of the objective reality underling their stances – but sometimes, on some issues, we are close – climate change springs to mind.

While I would not seek to make any new law to diminish or restrain the right of any person or publisher to express the most trenchant partisan opinions we must ask ourselves this question: is there a risk that in this proliferation of opinion, this electronic 21st century version of a snowstorm of 18th century pamphleteers, we lose sight of the reasonable point of view in the middle. Do we run the risk that every opinion we see or hear is an angry and indignant one?

Now we are a long way from the United States in this regard, but I think it is a fair observation to say that their politics has become more negative and more bitterly partisan and that this has been reflected in and amplified by a more partisan media – whether it is the cable news channels or the ferocity of much of the blogosphere.

Many people have argued that the Internet offers the chance for citizens journalism – whether it is small news websites, personal blogs or twitterstreams. There is no doubt that wireless broadband and smart phones have revolutionised newsgathering. Right now several billion people around the world have the ability to take a picture, a short movie and upload to the Internet where, conceivably it could be seen by millions within minutes.

If the Assad regime finally falls, the pictures of police brutality posted from Syrians’ smart phones will have had no small part in it.

And at a rather less heroic level, I am still amazed that I can, as I did on Monday night, knock out a blog on my iPad, post it on my website, tweet it and in those few minutes draw it to the attention of more than 77,000 people.

Yet if the Sydney Morning Herald and The Age and The Australian and even The New York Times were to close or shrink to shadows – do we really imagine the great task of reporting, explaining, investigating the powerful and holding them to account can be taken over by twitter and facebook?

I doubt it.

Our society, our democracy, needs journalism and we need journalists. We need a free, well resourced and independent media as much as we need our politicians and parliaments. We do not need, as Jefferson surmised, to consider whether we would rather have a government without newspapers or newspapers without a government. We need both.

So what is to be done?

We need to recognise that the whole edifice of our fifth estate, of our journalism, has been built on a foundation of newspaper journalism and that that foundation is crumbling.

The management of the media companies will deny that the end is nigh. I hope they are right.

But we should not assume, Micawber like, that something – the iPad perhaps – will turn up to set things right.

Life after newspapers is not just an issue for reporters.

We are very fortunate indeed in Australia to have the ABC and of course the SBS. The ABC’s importance in Australian news and journalism grows apace – partly because the rest of the industry which is funded by diminishing advertising dollars is in decline and partly because it has expanded its journalistic output and its reach with a 24 hour news channel, online news coverage which is more than just transcripts and summaries and of course through podcasts and iview. The news output of the ABC has never been bigger nor its reach wider.

It is far from perfect, but it does have an obligation to be balanced which it takes seriously. I think it helps to have the ABC run by someone who comes from the news rather than the entertainment side of the business.

There has been a lot of discussion about not for profit online news publications like ProPublica in the United States.

The idea of philanthropic tax-advantaged support for quality media is superficially enticing. In a way it is not so distant from the world we’ve know until now, where the ownership of media assets has often been associated with a particular type of individual – usually described by the shorthand term ‘media mogul’ – whose motivations were not simply commercial.

ProPublica in the US, an online media outlet which has won plaudits and prizes for the quality of its investigative journalism, and which has been supported in financial terms by a long list of respected charitable trusts.

ProPublica was founded and most significantly backed by the Sandler family and the critics of ProPublica have latched onto the way they made their money – by selling a home mortgage business to Wachovia Bank (which subsequently went bust) shortly before the sub-prime mortgage implosion and the GFC which followed.

The Pew Research Center looked at not-for-profits as business model and found that 44 per cent were clearly of an ideological nature. It concluded: “The 46 national and state-level news sites examined—a group that included seven new commercial sites with similar missions—offered a wide range of styles and approaches, but roughly half, the study found, produced news coverage that was clearly ideological in nature.

"Sites that offered a mixed or balanced political perspective, on the other hand, tended to have multiple funders, more revenue streams, more transparency and more content with a deeper bench of reporters.”

In a sense there is nothing new in this. Why should we be surprised sponsors of not-for-profit online (or indeed hardcopy) newspapers are motivated by political agendas – there is a long list of press barons, past and present, who have owned and often subsidised newspapers for no reason other than the power and influence it brought them.

Overall I think there is more to welcome than to fear in philanthropic sponsors of newspapers – some will be biased to left and right, but not all of them will be and if they wish to attract a wider range of sponsors to share the expenses, they will be wary of extremism.

This will come into focus in Australia early next year, when Graham Wood – the successful entrepreneur behind Wotif and hefty donor to the Greens – launches his Global Mail (with former ABC reporter Monica Attard at the helm and other respected journalists on the payroll).

Mr Wood shouldn’t be surprised if his vehicle is treated with scepticism at least at the outset – but the Packers, Murdochs and Fairfaxes have all used their papers and media to run political agendas and ultimately the calibre and balance of any newspaper is judged by its readers who have more interest in the journalism and the owner’s commitment to that journalism, no matter how controversial, than to his or her political interests.

Many governments have provided subsidies to newspapers to keep them afloat. That’s not an entirely new phenomenon. The establishment of the US Postal Service in 1775 was in large part to enable newspapers to be more widely and inexpensively distributed across the country.

I don’t think there would be any enthusiasm either in newsrooms or in Canberra for government subsidies to go to newspapers.

There is however the precedent of the ABC, but its funding is entirely from Government, locked in over a long term and buttressed by a strong culture of independence.

However there would be some merit in considering whether some level of support could be given, in terms of deductible gift recipient status, for not for profit newspapers, online or hard copy or both, which committed to a code of conduct analogous perhaps to that subscribed to by the ABC.

I simply pose this as something to consider – at this stage the Coalition is looking for ways to cut expenditure and new tax breaks are not in the offiing, but in the interests of looking beyond the next few weeks or even the next election, we should also be looking hard at how we ensure the survival of journalism.

Now I imagine many of you here are students of journalism and no doubt worry that you are stepping into an industry which is about to expire.

Well its not that bad. You are not signing up as cabin boy on the Titanic’s last voyage.

But your journey of journalism will be, potentially, the most exciting of all. At times like this, when the establishment is shaken to its foundations and the old order changeth yielding place to new, the young and the enterprising have the chance to take what is enduring – objectivity, accuracy, fearless independence – and build new platforms from which to launch their journalism.

Embrace the brave new world – we are counting on you.

Comments welcome below.