Your home internet connection works in one of two ways. One involves using a copper wire, probably your telephone line, to send electrical signals from the internet provider to your home and back. This technology hasn’t changed much since the days of the telegraph. The other technology involves the use of optical cables, which convert electrical signals into light and back. This increases the speed of data transfer because light signals can travel longer distances without distortion.

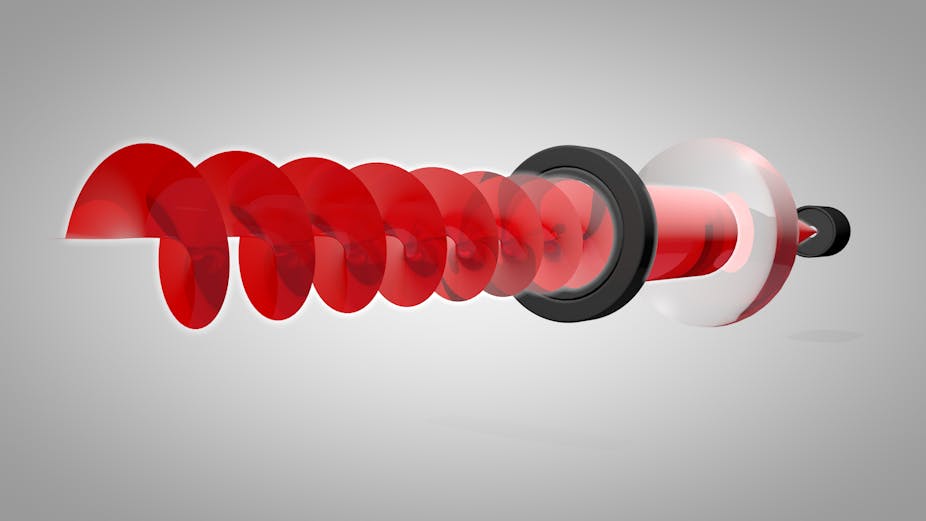

Now scientists are exploring a new way of transmitting data through using “twisted” light beams. The light waves in these beams form helical patterns – similar to the structure of DNA – rotating about a central axis. Because this is different from the standard light beam used for communication, twisted light could be a new communication channel in optical cables.

Data transmission across optical cables involves the transfer of 1s and 0s from one point to the other. Standard methods use the presence and absence of a light beam to represent those 1s and 0s. However, this method puts a physical limitation on how many beams of light can travel through a single optical cable.

Boosting data transfer

Twisted light beams represent a different method to transfer the same data. Because its properties are unlike that of normal light beams, they can be coded differently. And because this coding won’t interfere with the standard methods, it could dramatically increase the data-carrying capacity of the same optical cables. Despite recent progress, however, the methods for generating twisted light are few and, crucially, they are slow.

To address these limitations, our team of engineers has developed a new acousto-optic device that can twist beams of light at speeds never before achieved. The device is also able to form a wide range of patterns, shaping and steering light beams with more dexterity than was previously possible. The results of the study were published in the journal Optics Express.

The new device consists of 64 tiny “piezoelectric” sound sources arranged in a ring, each of which act as high frequency loudspeakers. Piezoelectric materials convert electrical signals into vibrations – and thus sound. Together these sources are used to generate carefully controlled sound fields.

Let sound do the work

The key to twisting the light is that the presence of sound subtly changes the refractive index of the material through which it travels. The changing refractive index means that the direction of light is slightly changed, causing the shape of the light beam to change. With knowledge of the link between sound-wave intensity and its effect on light, almost any light beam shape can be created. In the device we used twisting sound waves to imprint the laser beam and form twisted light beams.

While this form of twisting has been achieved before, our device can produce the results extremely quickly. All we need to do is change the electrical patterns on the piezoelectric material, which changes the sound field, eventually causing the shape of the light beam to change.

We can achieve millions of different patterns per second. This means that in the future laser beam-based devices will be able to be reconfigured much faster than is currently possible. Previously, the fastest achieved is a few thousand refreshes per second. This difference matters because, without such rapid refresh rate, the technology won’t be able to compete with standard optical communication technology. In some way this difference in speed is like that between dial-up internet and broadband.

In addition to communication, the ability to shape, steer and twist laser beams is useful for many other optical applications, such as optical tweezers, which are light beams that can hold onto cells or similar tiny objects. In many of these applications speed is the key so we are hoping that our new device opens up some exciting possibilities well beyond what we have imagined.