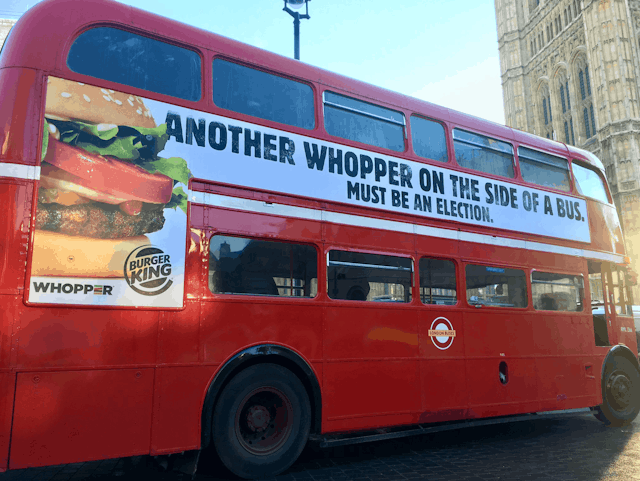

The UK’s 2019 general election is already being talked of as one of the dirtiest on record and one which has broken traditional media’s hold on political campaigns. Broadcasters have been wrong-footed and newspapers strangely marginalised as the fight has been taken to social media and populist buttons pressed wherever they can be found. And voters are weary.

As Peter Geoghegan and Mary Fitzgerald of OpenDemocracy wrote in the New York Times recently:

Pity British voters because they are being subjected to a barrage of distortion, dissembling and disinformation without precedent in the country’s history. Long sentimentalised as the home of ‘fair play’, Britain is now host to the virus of lies, deception and digital skulduggery that afflicts many other countries in the world.

Yet, as with technology, Amara’s law may apply: the impact of this campaign may be overestimated in the short term and underestimated in the long term. The list of offences has been well documented – but so far there seems to be little political price to pay.

The Conservatives rebranded their Twitter account to look like an independent fact checking account during a leaders’ debate, tried to “Google-jack” the Labour Party’s manifesto launch with a fake news site. They edited a video of Labour’s Keir Starmer to look as if he couldn’t answer a question and doctored another to look as if senior BBC journalists agreed with their policies.

Meanwhile they reneged on talks for Boris Johnson to be interviewed by the BBC’s Andrew Neil (as one Tory apparently briefed journalists: “Better to take the hit for being chicken than undergo that” and refused to appear on Channel 4’s climate debate – instead sending Michael Gove and Johnson’s father Stanley as surrogates.

The Liberal Democrats have been criticised for including misleading bar charts in campaign literature which overstated their position as well as distributing campaign literature designed to deliberately look like independent local newspapers. They have also had to discipline a staff member for faking an email in order to quash a news story they had branded “irresponsible”.

Labour has been less obviously mischievous, but Jeremy Corbyn brandished alleged trade documents that had been lurking online for weeks as “leaked proof the Tories want to sell the NHS” and refusing to answer questions on topics not of their choosing.

Tory ‘young Turks’

The Conservatives brought in a young digital team under Isaac Levido, an Australian political campaigner, to use the tactics that worked for Scott Morrison in the Australian election earlier this year. Working from what’s apparently called “the pod of power” in Conservative Central Office, they produce rapid raw social media content, designed to shock people, arouse emotion, unlock anger, excitement and fear in what’s called the “battle of the thumbs” – a reference to the importance of smartphones and sharing online content.

Perhaps, with public trust in politicians collapsing, they feel they have nothing to lose. But at the heart of these tactics is a cynical view of the public which cannot sustain a healthy political base in the long term.

Meanwhile, trying to find a legitimate middle ground in a polarised world where you are “either for us or against us”, appears to be a mug’s game for the broadcasters – which are regulated to be impartial and accurate. The politically committed – who can regard any scrutiny as partisan – aren’t interested in definitions of impartiality. Many would argue it is now irrelevant – hence the complaints about false balance and public calls for broadcasters to “call out the truth” rather than just present competing arguments. And the BBC has wobbled with some minor editorial errors which have been reluctantly acknowledged and jumped on by those searching for signs of bias.

Channel 4 has taken a belligerent stance, with its head of news and current affairs, Dorothy Byrne, calling Boris Johnson a “known liar” at the Edinburgh TV Festival in the summer.

The broadcaster also took an unflinching approach to “empty chairing” the prime minister when he turned down a place at their climate debate.

In return the government made menacing noises about reviewing the channel’s remit. Commendably bold by the broadcaster perhaps, but belligerence should be a last resort – as a former chair of Channel 4 used to say: “Don’t drive at a brick wall, drive round it.”

In contrast, the BBC having first stood firm when the prime minister decided not to submit to a forensic cross-examination at the hands of Andrew Neil (unlike other party leaders), then gave way and provided a softer seat on the Andrew Marr Sunday morning show – arguing they were still trying to persuade him to do the tougher interview as well. Don’t hold your breath. It suggested vacillation at a time which called for steadfastness.

Broadcasters appear wrongfooted, pushed into unhelpful stances, and newspapers’ once strident voices now struggle to be heard in the online cacophony. But beneath the noise and smoke of social media, there has been plenty of good reporting. As the director of BBC News, Fran Unsworth, wrote in The Guardian, for all the criticism of the broadcaster’s coverage – some justified, much not – it has continued to provide in-depth interviews with leaders, fact checking, policy analysis and more.

It’s there if you look for it – and broadcasting is still trusted more than print. And through a storm of partisan accusations broadcasters have steered a fair course. So maybe this is all just the melee of a rancorous campaign and, afterwards, calm will return. Maybe.

Storing up trouble

But this is where the longer-term consequences come in. There’s no question the political parties have sought to undermine the media by pressing populist buttons and disregarding the norms of election campaigns. And our media institutions have struggled to adapt swiftly to the new tactics – to the tone and timescale of digital campaigning and unconventional and disruptive strategies. As a result, they can appear clumsy and leaden-footed.

The public broadcasters, like other areas of public life, have been through a difficult decade of austerity funding where financial efficiency has been placed above public value. Now both the BBC and Channel 4 are likely to emerge from this election having alienated whoever wins. That’s not conducive to a strong stable broadcasting environment ready to shoulder the responsibilities we expect of public institutions.

The UK’s broadcast channels – including ITV, Sky and Channel 5, alongside the BBC and Channel 4 – have been a national success story, holding the country together with moments of common experience, reflecting life across all the nations of the UK. In fragmenting times with populism on the rise, that seems less achievable. Consensus is breaking down and is being replaced with pervasive scepticism and cynicism. The growing divisions are not just between Remain and Leave voters, but between urban and rural communities, north and south, rich and poor, the informed and the uninformed, young and old.

This is partly driven by economic policy, but more by big technology. Social media has given everyone a voice – including those with little to say – and has lured the media and politicians into a populist strategy of trying to reflect the views of the masses. The big tech platforms have soaked up public attention, broken media business models, invaded our lives and sold our data. They have provided a platform for propaganda and disinformation which would not be allowed in the analogue world and placed their own profits above the public good.

With Artificial Intelligence developing rapidly, society’s management and understanding of the world of information is likely to fall even further behind. In spite of the many calls for regulation or greater media literacy education, it seems unlikely any new government will have the courage or priorities to take on Facebook and Google.

There is, as commentator Azeem Azhar has described, an accelerating gap between new technologies and institutions’ ability to respond. This is reflected in the slow responses, remote tone and a closed approach to managing crises that we see in pubic broadcasters. Although they believe they are adapting to the new digital world, the corporate culture running through them does not change. It’s still run by officers and served by infantry.

How might this be different for another election in five years’ time? The UK needs a more transparent approach to political campaigns. As Sky’s editor-at-large Adam Boulton reminded us last week there is support for an independent commission to organise future TV debates, similar to the US Commission on Presidential debates. This would mean the democratic imperative of aspiring leaders talking to the public was managed by an independent, transparent and formal process – no longer stitched up in locked room deals and gentlemen’s agreements.

And online political advertising and party funding need to be openly and transparently regulated and organised. No more foreign oligarchs paying hundreds of thousands for a dinner or game of tennis and no more targeted Facebook ads with no requirement for truth or accuracy and no visibility beyond the targeted groups.

The broadcasters, always competitive, need to collaborate in managing party relations and in managing their relations with the tech behemoths. Going it alone they will be stepped over. They need far greater transparency – explaining their values and judgements, the “why” as well as the “what” of their decision making to keep the public onside.

And they may need to wean themselves off a secretive lobby system quoting unattributable anonymous sources with the latest scuttlebutt. Let’s throw the doors open and have on-the-record press briefings in Westminster.

Both politics and media need greater diversity. As one senior broadcasting executive told me this week: “It’s not enough to invite them to the table – we have to hand the table over to them”, by which he meant the young and the ethnically and socially diverse.

But of course none of this is likely to happen swiftly. The price of political dirty tricks is low or non-existent. The lure of keeping power behind closed doors is too great. Brexit will dominate public life for at least another five years. But the cynicism of political lies and the fear of losing control by opening up the corridors of power can’t last. Either politics and institutions, including the media, adapt rapidly – with transparency, diversity and openness – or the historic social and technological changes we are experiencing will eventually break them.