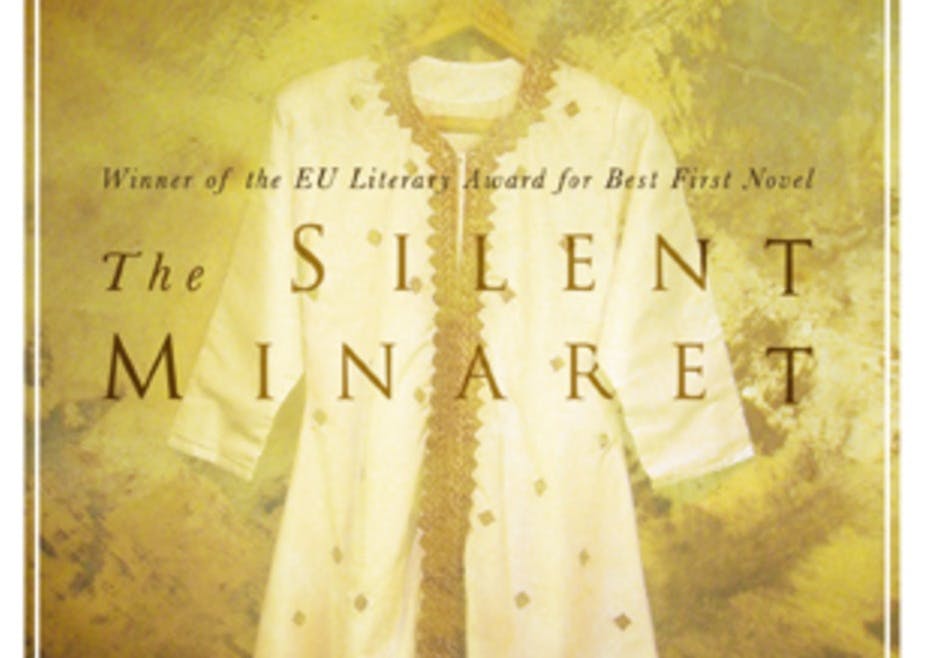

This is the fourth in a weekly series called “Under the influence”, in which we ask experts to share what they believe are the most influential works of art in their field. Here, Neelika Jayawardane introduces Ishtiyaq Shukri’s first novel, “The Silent Minaret”, published in 2006 by Jacana.

“The Silent Minaret” is Ishtiyaq Shukri’s first novel. It centres around the unexplained disappearance of a young South African-born student, Issa Shamsuddin, in London. We never learn of the reasons behind the disappearance.

Through the use of a variety of narrative techniques, Shukri links colonial-era tactics used to subdue people and control their resources with similar strategies employed in both apartheid-era South Africa and the post 9/11 world.

After reading “The Silent Minaret”, there’s no mistaking that the tactics used by 16th- and 17th-century empires – including the abduction, transport and imprisonment of dissenters in distant island-gulags – are parallel to those that have been used by the empire-builders of the 21st century.

We realise, as we follow Issa’s intellectual trajectory, that during the so-called global “war on terror”, the US and its powerful allies have similarly confiscated vast swathes of land, displaced millions of people and forcibly taken over access to this century’s most valued resource – petroleum.

Why is/was it influential?

This novel resonated with me in a way few books have. I would even venture to say that my scholarship is based on the initial research I did for my scholarly writing about Shukri’s first novel.

Issa Shamsuddin, Shukri’s protagonist, begins his political journey in South Africa as social, intellectual and political outsider, as an in-between Other who identifies with no ethnic or national group. His position as an Other allows him to question easy nationalism, revealing the ways in which the privilege of belonging is made possible, most often, using violence and exclusion.

Shukri has said in a Litnet interview that he is, in some ways, “homed” in many places, be it Palestine, Oman, London or South Africa. He declares, very clearly, “I don’t believe in the nation state.”

He details why a passport does not make a person, nor give a person an identity or sense of belonging. That’s especially something that becomes apparent when you realise that your passport “belongs to the South African government, and […] can be withdrawn at any time”, he said in the LitNet interview. His novel is a challenge to such easy, go-to sorts of identity locators.

My relationship with the book

These are the issues I’ve dealt with as a person who was born in one country (Sri Lanka), raised in another (Zambia), educated in yet another (the US), and lived somewhat itinerantly in about five countries (a list that includes South Africa). That’s without having any sense of national pride in any one of them.

I have a visceral reaction to being asked “Where are you from?” That question usually comes from those who wish to circumscribe you through the category of nation – and then, by the mythologies of race, gender and the like that the questioner associates with the location you are supposedly “from”.

The question assumes, with the 20th century’s false elevation of nation above all else, that one’s nation will determine one’s loyalties and cultural and psychic belonging, as well as what one will be like, in general. Shukri gets us to question that powerful political-cultural myth of being tied to nation – it’s a remarkable achievement in fiction.

Why is it still relevant today?

“The Silent Minaret” follows the ways in which empire reproduces itself in different locations, with different actors. For instance, there is a section where we learn about how Israel is systematically eradicating entire Palestinian villages by diverting flowing bodies of water into Jewish settlers’ farms. This, while building a vast, snaking concrete wall across lands that once belonged to Palestinians.

Shukri shifts the reader’s line of thought from one war and contested location to another, creating layers that reveal the ways in which imperialism, conquest and erasure work, rather than creating easy parallels.

Birds of a feather

Similar books incude:

Shukri’s second novel, “I See You” (Jacana, 2014), published eight years later;

“Fugitive Pieces” by Anne Michaels (Vintage, 1998); and

“Out of Place” by Edward Said (Vintage, 2000).