UNESCO, the body that lists world heritage areas, continues to express extreme disquiet about the state of the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area. But it has now postponed to February 2014 consideration of the reef’s downgrade to “World Heritage in Danger”.

UNESCO had planned to decide on “In Danger” listing for the reef in June 2013, taking account of measures put in place over the last year. However, information on which UNESCO can make a judgement is not yet complete. Queensland is still assessing the environmental impacts of new ports. And the Queensland and Commonwealth government reviews on implementing best practice in management and development of Gladstone Harbour – in the World Heritage Area – are not yet at hand.

Two requests by UNESCO for information and action have recently been fulfilled. These are the second report card on the condition of the reef and a commitment by the Commonwealth to continue funding Reef Rescue, a mechanism to address declining water quality.

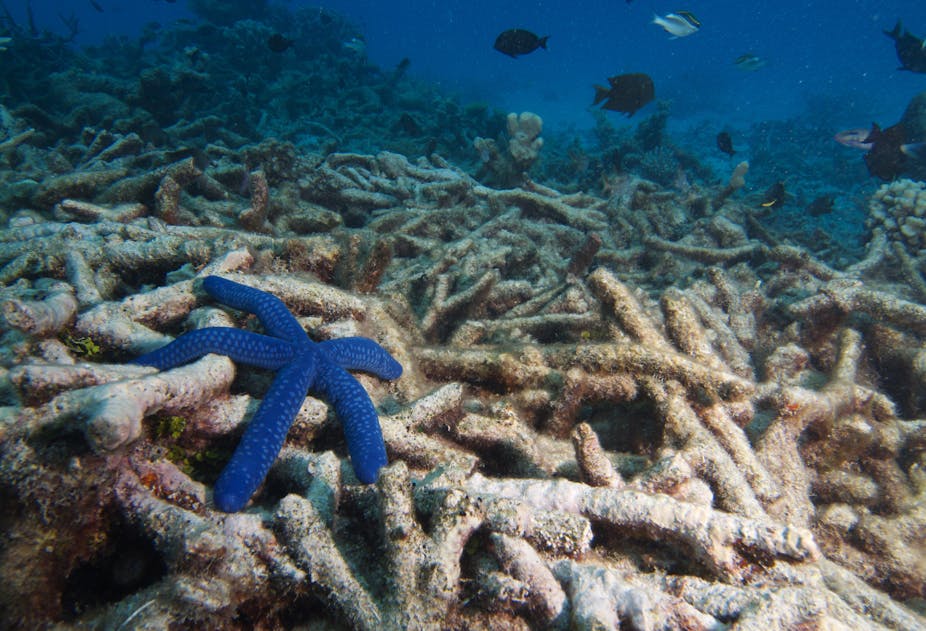

The second report card, while out of date as it deals with 2010 data, is positive. It shows small reductions on the reef of harmful nutrients and sediments from farms. But great improvements are still required. Water quality is only moderate, seagrass cover is poor and coral status is moderate to poor. Moreover, 16 tonnes of pesticides are still dumped in the lagoon of the reef annually and herbicides have been detected 15km offshore.

Port approvals and assessments

UNESCO has given the OK to development of existing ports along the Great Barrier Reef coast. And in October 2012 the Commonwealth approved an extension at the coal terminal at Abbot Point.

While only an extension, and not a new port, it will still harm turtles and dugongs. And the project continues the damaging practice of dumping dredge spoil on the reef.

The pivotal issue for UNESCO now is the development of new ports on the GBR coast.

UNESCO notes anxiously that the Queensland government has flagged new port developments at locations such as Balaclava. This project, plus new ports at Fitzroy and Wongai, would eventually export 58.5 million tonnes of coal annually. But all three are located in pristine coastal environments, harbouring threatened species, migratory birds and wetlands.

The Federal Environment Minister can decline these new port proposals. But, to now, very few such developments have ever been denied. The minister may decide to apply strong conditions when approving the new ports. This is unlikely to satisfy UNESCO though; it wants Australia to “fully implement” its requests “by making an urgent commitment to ensure that no port developments or associated port infrastructure are permitted outside the existing and long-established areas within or adjoining the property”.

If there is a showdown, it will likely happen in February 2014.

Coal, climate change and the reef

Climate change is perhaps the greatest threat to the integrity of the Great Barrier Reef. Yet, ironically, only coal mining and transport – not coal burning – are being assessed for their environmental impact.

The proponents of coal mines and port developments are supposed to include socio-economic assessments in their environmental statements. If these were done properly there would be an assessment of external costs, including costs to the world at large as well as to Australia.

An external cost of Australian export coal is that imposed globally by emissions when it’s burnt. The greenhouse gas emissions of export coal are already greater than Australia’s total emissions from all sources, as shown in the chart above. Australian coal exports are forecast to more than double by 2035 and so will the consequential emissions of carbon dioxide equivalent.

I apply an external cost of US$10 per tonne of CO2-equivalents (likely to be assessed as much higher in the future) to the forecast of 1,641 million tonnes emitted in 2035. This gives a total external cost for coal exports in that year of US$16.4 billion. The size of such costs is food for thought.