Australia is famous for its natural beauty: the Great Barrier Reef, Uluru, Kakadu, the Kimberley. But what about the places almost no one goes? We asked ecologists, biologists and wildlife researchers to nominate five of Australia’s unknown wonders.

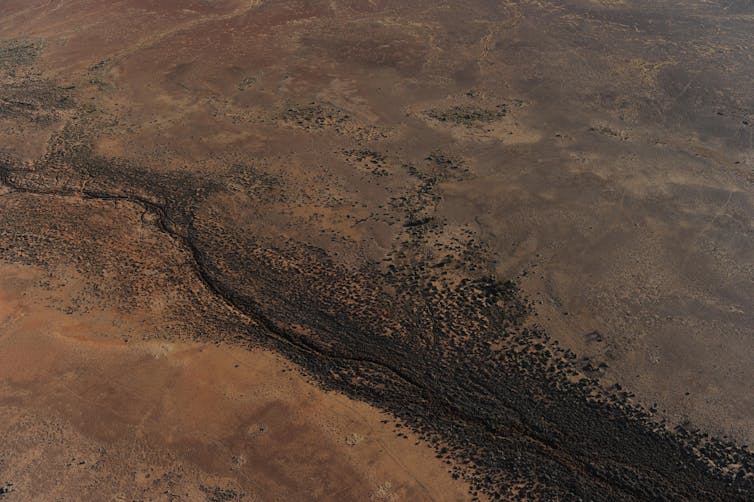

Out in the Lake Eyre Basin, there is no more idyllic place to camp than beside a waterhole on the Diamantina River. The tranquil water belies that this is a land of extremes, with soaring summer heat and cold winter nights. This is an ethereal landscape where the harshness of the surrounding desert meets the productive waters of myriad desert rivers. These rivers are characterised by unpredictable flooding and drying; boom and bust periods that drive the ecology of the massive heart-shaped river basin that dominates the centre of Australia.

The waterholes on the Diamantina River are currently in a “bust” phase; it has been 18 months since the last major floods pulsed through, filling the complex array of small channels, billabongs and lakes that intricately link this most complex of the world’s rivers. It will be another eight years before the next big flows, the next major “boom”.

Floods herald boom times, triggering mass breeding of everything from the microcrustaceans at the bottom of the food chain to pelicans at the top. Inevitable busts follow, extending much longer and reducing the rivers to a series of disconnected waterholes.

But the system remains ever-changing. Small flows, usually from local rainfall, top up the waterholes. These reduce declining water quality, including increasing salinity and decreasing oxygen, and sometimes even trigger small scale breeding of fish and waterbirds. These “in-between” flows keep the system ticking over, with water in the waterholes and wetlands, ready to make the most of the larger rainfall events that occasionally push into this arid landscape.

Floods and dry times drive incredible productivity, not only of fish and waterbirds, but also wildflowers which carpet the floodplains. Lush pastures after the boom times also provide some of the best cattle country in Australia, renowned for its organic beef. Today’s graziers practice the same strategy as the great cattle king, Sir Sidney Kidman, did during the late 1800s and early 20th century, shifting the cattle during the bust times and moving them in during the boom times.

These unique, complex rivers flow through vast floodplains and intricate channels that cover the arid landscape, eventually leading to Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre; its new name recognising its importance to Aboriginal people.

This vast lake, the fifth largest terminal lake in the world, covers 9,690km2 of mainly dry salt until the rivers flow across its surface.

The interaction between its 400 tonnes of salt and the highly variable inflowing freshwater, predominantly from the Diamantina and Cooper, define its aquatic ecology. Few animals or plants tolerate the extreme salinity of Lake Eyre, which sometimes exceeds that of seawater. But, given enough freshwater, an explosion of life is triggered.

During these large and medium floods, the lake takes off biologically. Warm water and food provide ideal conditions for millions of invertebrates to proliferate and soon the fish and waterbirds arrive.

Freshwater invertebrates hatch from sediment or are transported by floodwaters and increase exponentially, within days and weeks. With all this food, fish build up in extraordinary numbers; after the large floods of the 1970s, an estimated forty million dead fish lay in contours around the edge of Lake Eyre.

Even in moderate floods, Lake Eyre can support large concentrations of waterbirds. For example, in the 1990 flood of Lake Eyre, there were more than half a million waterbirds, of which more than 100,000 were migratory shorebirds where Cooper Creek flowed into a relatively small part of Lake Eyre.

During large floods, breeding colonies of Australian pelicans, Silver gulls and Banded stilts nest on the islands in extravagant numbers. In 1990, a hundred thousand pelicans raised an estimated ninety thousand chicks. The Banded stilts, somehow knowing, arrive from the Coorong in South Australia to breed.

Inevitably, times of bounty come to an end as the bust sets in and the lake dries. Waterbirds usually get away, sometimes moving long distances. After the 1974-1976 floods, pelicans hatched and banded on Lake Eyre moved as far as Palau, Christmas Island and New Zealand.

The health of the whole area, the lake and its rivers, is fundamentally dependent on the unimpeded supply of freshwater. The most serious threat remains the development of water resources upstream and the impact of mining, particularly in Queensland. Water resource development would reduce the amount of water in the rivers, no longer topping up waterholes and perhaps not making it to Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre. Mining also brings the risk of pollution.

It is the boom and bust nature of the region that drives the ecology of these systems. But the busts can easily be increased by water resource development, affecting the entire ecology of the Lake Eyre Basin and the people that depend on it. It wouldn’t take much to knock the magic out of this most wonderful of Australia’s environments.

Read all the unknown wonders here.