To mark Wallacea Week, a series of public lectures and exhibition on the Wallacea region of Indonesia, The Conversation presents a series of analysis on biodiversity and history of science in Indonesia. This is the first article of the series.

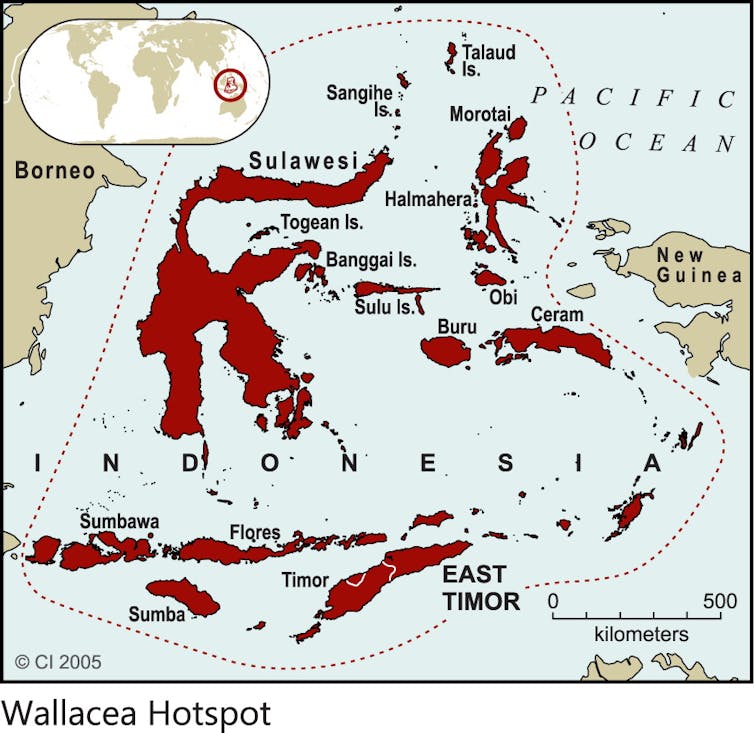

The central islands of Indonesia - between Java, Bali and Kalimantan (also known as Borneo) on the west and Papua at the eastern end of the country - is a place of wonder, a living laboratory for the study of evolution.

It’s called Wallacea, named after Alfred Russel Wallace, the 19th century English explorer and naturalist. On his exploration in the Indonesian archipelago (then known as the Malay archipelago) Wallace developed his theory of natural selection.

He noticed that the islands of Kalimantan and Sulawesi as well as Bali and Lombok have very distinct animals even though the islands are next to each other. He proposed an invisible line runs between Kalimantan and Sulawesi and Bali and Lombok separating the faunas.

In Kalimantan and Bali live animals such as tiger, rhinos and elephants, which now, due to human population expansion, are endangered. In Sulawesi and Lombok to the east of the small Mollucas islands, we find marsupials, a variety of peculiar looking monkeys, and interesting endemic animals. Endemic animals means they are native or restricted to an area.

The invisible line is now known as Wallace’s Line and the region between it and the island of New Guinea has come to be called Wallacea.

Scientists today know that Kalimantan and Bali were connected as part of Sundaland, a large landmass that includes the Malay Peninsula on the Asian mainland as well as Java and Sumatra. This landmass was exposed for 2.6 million years until ice caps started to melt around 14,000 years ago, submerging part of the landmass and creating the Indonesian archipelago.

Creatures of Wallacea

Wallacea includes the large island of Sulawesi, the Mollucas - the various small to medium-sized islands to the east of Sulawesi and the “Banda Arc” islands - and the Lesser Sundas or Nusa Tenggara, south of Sulawesi and the Moluccas.

Wallacea is a transition zone between the great Indo-Malayan and Australasian biogeographical realms. Millions of years of relative geographical isolation have allowed fascinating and highly endemic fauna to evolve here.

Wallacea is home to 697 bird species, of which 249 (36%) are endemic. The rate of endemism rises to a more impressive 44% if only the resident birds, or those that don’t migrate, are considered.

On Sulawesi and its satellite islands, there are 328 bird species, 230 of them resident and 97 species are endemic, among them the maleo bird.

Wallacea has a total of 201 native mammal species (excluding whales and dolphins), 123 of which are endemic. If we exclude the 81 bat species with their greater capacity for dispersion, the rate of endemism increases to a very high 93%.

Sulawesi, the largest island in Wallacea, has the highest number of mammals, with 132 species, of which 83 (63%) are endemic.

It holds important flagship species such as the anoas (Bubalus depressicornis), diminutive buffaloes that live in the forests of Sulawesi, and the babirusa (Babyrousa babyrussa), an unusual, enigmatic pig with long, recurved upper tusks that penetrate through the skin of the upper lip.

Sulawesi’s primates are also special. At least seven species of macaques are unique to the island. Sulawesi also has several species of tarsiers - tiny, goggle-eyed creatures that look more like mammalian tree frogs than monkeys.

Reptile diversity is also quite high, with 188 species, of which 122 (65%) are endemic. The best known reptile in Wallacea, and one of Indonesia’s most famous species, is the Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis) or “ora” in local language.

Komodo is the heaviest lizard in the world (males can reach about 2.8 m in length and weigh about 50 kg). They live only in the tiny island of Komodo, the neighbouring islands of Padar and Rinca to the west, and the western end and north coast of Flores.

Most of the 210 freshwater fish species recorded from the rivers and lakes in Wallacea are tolerant of both fresh and salt water to some extent.

We still need more research in fish species. In the Moluccas and Lesser Sundas, the fish fauna is poorly known. But there appear to be around six island endemics. On Sulawesi, there are 69 known species, of which 53 (77%) are endemic.

At the northeastern corner of South Sulawesi lies the Malili Lakes, a complex of deep lakes, rapids and rivers. Here, at least 15 endemic beautiful telmatherinid fishes have evolved.

The plants of Wallacea is not as well known as that of its neighbours. Fewer botanical specimens per-unit-area are collected than on any other major islands in Indonesia.

We also don’t know much of the invertebrate fauna of Wallacea. However, some groups, such as the enormous birdwing butterflies are better known.

Wallacea also has the world’s largest bee (Chalocodoma pluto) in the northern Moluccas. The females can grow to 4 cm in length. They are also remarkable because they nest communally in inhabited termite nests in lowland forest trees.

Human impact

As elsewhere, things have changed dramatically in Wallacea during the course of the past century. The human population has nearly quadrupled. Development has grown tremendously in Indonesia in general.

The first commercial logging operation in Wallacea began in the early part of the century, and forests have been cleared for agricultural programs, for industrial timber plantations, and for land settlement schemes that resettled hundreds of thousands of people from densely populated Java to other less inhabited (but much less productive) corners of Indonesia.

This has greatly reduced the amount of forest habitat, particularly in the lowlands, and has caused dramatic and severe declines in the populations of many forest species (many as much as 90%).

Much of the remaining forest is now given out in timber concessions of various kinds.

Furthermore, forest and land fires continues to be a problem. It is now greatly exacerbated by increased drying because of logging and plantation agriculture, and sometimes by intentional burning as well.

Overall, about 45% of Wallacea still has some forest cover; however, if one considers forest that is still in more or less pristine condition, the percentage drops to only 15%, or about 50,774 square kilometer.

At this point in time, forest protection in Wallacea is moderate at best. Protected area coverage is around 24,387 square kilometer, or 7% of original extent.

Of course, establishment of protected areas is only a beginning. Once created, they need management and the cooperation of local people, the government, and the private sector in order to be successful in conserving biodiversity. For millions of years, fascinating creatures have managed to diversify and evolve over millions of years. We have a moral obligation to protect this wonder.