As part of ongoing research on both radical Islamist and far-right extremism, I spent the best part of 2009 following the activities of one British city’s al-Muhajiroun group. Also known as Islam4UK, this small group led by Omar Bakri and then Anjem Choudary has been a long-term irritant to the government, as well a staging post in the lives of many British terrorists.

Many of those who have committed terrorist violence in the UK and abroad have been part of or connected to the group. Khuram Butt – one of the three London Bridge attackers – is just the latest. Butt was a known follower of the al-Muhajiroun network.

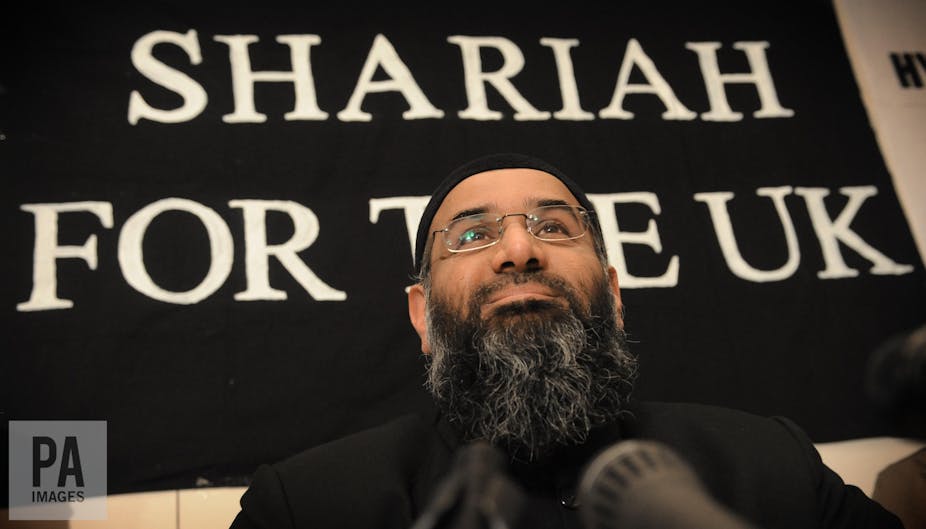

Demonstrations and media appearances by its leaders have caused outrage time and time again – and led to the forming of the right-wing English Defence League (EDL) in opposition to its ideas. In both 2006 and 2010, the group was banned on the grounds of glorification of terrorism, only to reappear under other names.

The group was formed in 1996, when Omar Bakri was expelled from Hizb ut-Tahrir, an Islamist group that aims to restore the historic Caliphate to unite all Muslims. Hizb ut-Tahrir works politically and intellectually, and so did not appreciate Bakri’s “aggressive populist approach and high media profile … street demonstrations, mass rallies and public conversions”. While al-Muhajiroun shared some of Hizb ut-Tahrir’s long-term goals, it seems its immediate aim was to be visibly disruptive.

A year later, the journalist Jon Ronson made a documentary called Tottenham Ayatollah, painting Bakri as a clown. Even in this period, however, there were claims from others, and boasts by Bakri, that the movement was also recruiting Britons for military action in Kosovo, Chechnya and Kashmir.

Pre-empting changes to the law, Bakri announced the dissolution of al-Muhajiroun in 2004. It then reformed under other names including Saved Sect, al-Ghurabaaa (both banned in 2006) and Ahl ul-Sunnah Wa al-Jamma, with many other names as “platforms”. After the 7/7 attacks in London in 2005, Bakri left for Lebanon and was barred from returning to the UK. It was then that Anjem Choudary moved to centre stage as spokesman. Choudary was sentenced to prison for five-years in 2016 for activities supporting so-called Islamic State.

Watched closely by the police

I first met the group at a local authority community centre after being given a leaflet for an event on the Khilafah (the Caliphate). Choudary was the guest speaker, and the local activists did talks for an audience of around 30, and showed videos about the victims of war and their view of life in a Caliphate. I then went along to their da’wah (proselytising) stalls two or three times a week, to talk with and occasionally interview them, and to watch as they talked to passersby.

I was not the only person to be taking a long-term interest in them. The police had raided some of the groups’ houses before, and local officers would also turn up to the meetings and the stall to collect samples of the leaflets, CDs and DVDs. These officers knew the activists by name, and would engage in conversation about the Islamists’ ideas and materials. Local politicians and leaders knew of them, too.

The group were not welcome in the larger mosques – although one mosque leader did point out to me that there wasn’t a lot they could do about the group leafleting on the street outside.

Occasionally, local youths would shout racist abuse at them as they drove past. Most of the time, though, their conversations with the general public and the police were calm and polite, even while they were trying to argue that implementing sharia law in the UK was the way to solve problems such as racism, drug abuse, and also to stop homosexuality and promiscuity.

In this, their analysis of the ills of society had some crossover with views held by others, Muslim and non-Muslim. But some of their solutions, like the suggestion that the local football ground could be used for stonings, were extremist. However, it is hard to know how seriously to take this kind of rhetoric when, at the same time, they’d be happy to go to the five-a-side pitch for a kickabout, and they talked about pop music and TV shows.

Skirting the edges of the law

What got the group’s spin-offs Islam4UK and Muslims Against Crusades added to the government’s banned list in early 2010 was not a terrorism plot, but the proposal of a march through Wootton Bassett, the Wiltshire town where British military war dead were repatriated, carrying coffins to symbolise dead Afghan civilians. The event was cancelled a week after the announcement, but again their provocative approach brought them headlines.

Demonstrations and conferences, some of which didn’t happen in the end, kept them in the news. These included the “Magnificent 19” event planned for the second anniversary of 9/11, the demo in Luton against returning British soldiers that led to the creation of the EDL, and poppy burning on Remembrance Day 2010. At the same time, many documentaries have been made about the group or individuals within it, and Choudary made multiple TV and radio appearances on Newsnight, The Big Questions and BBC Radio 4’s Today programme.

The al-Muhajiroun leadership has, over the years, attempted to act just within the law, while making statements and events that inflame public opinion. This seems to have helped them recruit new activists – and also recruit for the EDL and other counter-jihad groups. The government has responded by introducing definitions of “non-violent extremism” and “fundamental British values” that attempt to include this group while upholding as much freedom of speech as possible.

However, some of those involved in the group, including some of those who I interviewed, have been convicted of terrorism offences or carried out attacks. It’s possible that some had an interest in committing future violence before getting involved, hence the attraction of the group, and some may have developed it during or after involvement.

It’s very difficult to know who will graduate from controversial but legal activity – such as bragging and bravado about revolution, violence and “doing something” – to actually going out and committing murder. That said, being angry and talking about fundamental change ought not to be a crime. This is one of the difficulties of counter-terrorism policing and the government’s Prevent strategy.