If you’ve noticed the 1980s hit “Africa” playing on the radio more than usual, you likely weren’t listening to the original version by Toto. Instead, it was probably the recently released cover by Weezer, which has already been heard over 25 million times on Spotify.

Maybe you know the backstory: A teenage fan started a joke Twitter account, @weezerafrica, in order to persuade her favorite band to cover her favorite song. Days later, the hashtag #WeezerCoverAfrica went viral, and, after months of virtual prodding, the band indulged the request.

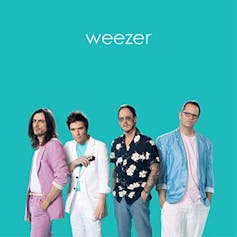

To everyone’s surprise, Weezer suddenly had a chart-topping hit – its best performing single in a dozen years. And it isn’t even the band’s own song. Now Weezer has released an entire album of covers – a self-titled EP affectionately known as the “Teal Album,” which has already hit No. 5 on the Billboard 200.

As a musicologist, Weezer’s successful foray into cover songs made me think about the overall trajectory of the practice.

They’re usually a fun way to memorialize an existing song and pass it along from one generation to the next. But the practice isn’t free of controversy.

Enriching our collective musical memory

The editor of a book on cover songs, communication scholar George Plasketes writes that covers are “about favorite songs and great songs. Classics and standards.” They show how “musical artifacts are kept culturally alive, repeating as echoes.”

To Plasketes, regardless of what a musician might add or subtract in the process, cover songs capture and convey a collective musical history.

The concept of covering has been around as long as music has been written down. The earliest choirs for Catholic masses often sang versions of earlier Gregorian chants. These “covers” were intended to both teach and entertain – to attract worshippers and spread Christianity. Then, as now, covers circulated culture.

Scholars have identified many categories of cover songs, but people are probably most familiar with two of them: the “straight cover” and the “transformative cover.”

The former, also known as a “karaoke cover,” sounds almost exactly like the original, which is the route taken by Weezer. Such an approach might pay homage to a music influence, like The Beatles’ “Twist and Shout,” which had been popularized by The Isley Brothers but was originally recorded by The Top Notes.

A straight cover can also form a sort of ironic commentary. Cultural theorist Steve Bailey notes that, while such covers “tend to ridicule the originals,” they also “celebrate the continued vitality … of the music and its importance.”

Certainly, there’s a dose of irony to Weezer’s “Africa” – the band recorded it at the request of fans, not necessarily out of some deep connection to the music or as a nod to Toto’s influence. We can’t be certain, but it seems as if Weezer’s poking fun at the ‘80s hit, while still staying true to the original.

More frequently, covers fall into the transformative category, which is when musicians put their artistic stamp on a song.

Consider a hit such as Whitney Houston’s “I Will Always Love You.” Houston was able to transform Dolly Parton’s original country song into a pop anthem.

Then there’s Aretha Franklin’s “Respect,” which famously flipped the gender dynamics of Otis Redding’s original – all of a sudden it was a woman asking “for a little respect when you get home.”

The contradictions of the cover

It’s fun to hear one performer emulate another or to experience a familiar song made anew. But the question of “who gets to cover whom” reveals one problematic aspect of the genre.

As white rock 'n’ rollers usurped black rhythm and blues artists in the 1950s, countless covers became known not as covers, but as the definitive version.

Did you know that Elvis Presley’s “Hound Dog” was originally performed by rhythm-and-blues singer Big Mama Thornton? Or that Bill Haley’s “Shake, Rattle and Roll” was first recorded by blues shouter Big Joe Turner?

These two versions are especially emblematic of the issue. Not only are the covers safer, less-sexualized renderings geared to a white teenage market, but their subsequent popularity severed the songs’ original associations with their black creators. Elvis and Haley earned millions of dollars off of this appropriation. Few hear “Hound Dog” and think of Big Mama Thornton.

On digital streaming platforms and automated playlists, cover versions of popular songs can still siphon attention and money away from the original. Enter any title from Weezer’s “Teal Album” into Spotify or YouTube and the new recordings sit right next to the originals. At the same time, this side-by-side placement might encourage deeper exploration of our musical past. If you realize that your favorite song is actually a cover, you might be inclined to listen to the original.

But do we need to know the original to appreciate a cover? Or even be aware that a song we know well is a cover to begin with? Listeners unfamiliar with Nine Inch Nails might believe Johnny Cash’s “Hurt” is originally his. No doubt similar assumptions have been made about Jimi Hendrix’s “All Along the Watchtower,” which is actually a Bob Dylan tune. Many other artists have also covered “All Along the Watchtower.”

If a song gets repeatedly covered, it could be a sign of its artistic strength. As professor of American literature and culture Russell Reising writes, “There’s clearly something about the Dylan original that not only continues to inspire performers but resonates with the socio-political events of our culture.”

Even great originals can possess a degree of unrealized potential just waiting to be discovered by the artists that cover them.