The British chancellor, Philip Hammond, was roundly criticised on November 19 after claiming there were “no unemployed people” during a BBC interview with Andrew Marr.

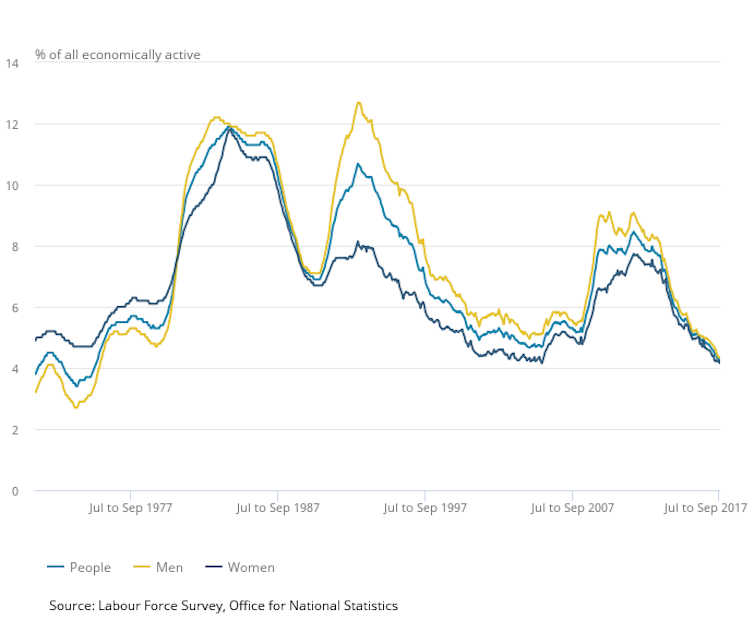

While the latest figures from the Office for National Statistics showed a fall in unemployment in the UK, there are still 1.42m out of work. And there is growing concern about the UK’s increasingly precarious and insecure labour market.

The numbers of people who do not have enough work, are on temporary or zero-hours contracts, and who are classed as self-employed but are actually working just for one employer still remain higher than before the recession of 2008.

This is coupled with welfare reforms that have affected those claiming unemployment benefits. Not least has been the introduction of Universal Credit, a one-stop benefit, which has intensified the conditions that are placed on people before they can receive welfare payments. This type of “welfare conditionality”, which includes demonstrating up to 35 hours per week job search activity, also applies to people who receive Universal Credit but are working.

We have been involved in several research projects about the issues facing people who move from the benefits system into insecure work. As part of an ongoing national study focusing on welfare conditionality, one man talked about his experience of starting zero hours work in food processing in the north of England. In his first week, he was told he would receive a text message saying whether he was needed the next day. For two days he didn’t receive any messages.

Then the third day they gave me an option to just go up there and be a spare, so literally if people don’t turn up you can go up there and stand around for half an hour and if they don’t turn up then they’ll use you. So I went up there, it was quite early in the morning, 7 o'clock; I was up at 5.45 to get there. I hung around for half an hour. I wasn’t offered any work.

This man did manage to secure more hours, but the job was still temporary and he remained on Universal Credit throughout this experience, knowing that he would be relying on the benefit again once the temporary work ended. This meant that in addition to worrying about whether or not he would have work from one day to the next, there were also still expectations on him from the Jobcentre to attend appointments and continue looking for work.

Corralled into precarious jobs

Precarious workers often work in several jobs, but can still live in deep poverty. People with precarious work often have unpredictable or insufficient working hours and schedules which lead to irregular income and significant pay penalties. This can in turn cause increased levels of debt, a limited choice of housing, or even eviction, as well as negative consequences for personal well-being.

Another of our studies showed that the first contact with precarious jobs often starts at the Jobcentre where claimants are encouraged, directed or coerced to apply for low-skilled, low-paid and precarious jobs, such as temporary agency work and zero-hours work.

Not doing so might lead to benefit sanctions – meaning their benefits will be suspended. A man we spoke to who lived in Derbyshire told us:

I got offered a job with an agency in Manchester with no expenses for travel and so on. I said ‘no’ and then was sanctioned for refusing work.

Not what workers want

Our research using the Annual Population Survey of over 100,000 employees in the UK is showing that precarious working contracts and conditions are driven mainly by employers’ demands for flexibility – not what workers want. Only one in five of temporary agency workers in the UK included in the survey actually prefer to work in a temporary job. Many of the people we interviewed would not choose to work for an agency, would not recommend working for an agency and would like to see zero-hours contracts banned. This is contrary to what the prime minister, Theresa May, claimed earlier in the year.

Employer-driven flexibility also puts people in a situation where they have a limited power to negotiate their working conditions, as our research and other studies have found. We heard many stories of how peoples’ working hours were cut, changed at a short notice or their jobs were taken away only because they weren’t – as one person we spoke to put it – “servile to management”.

Our research also shows that precarious working arrangements are also often coupled with employment practices that disadvantage workers. Many are often not provided with an employment contract or wage slips, and are not paid for holidays, sick leave or lunch breaks. Others are not paid for their work, as firms claims the hours were only an “induction”.

While government statistics may show a decreasing number of unemployed people, it’s too easy to point to this as a success. These figures hide the harsh experiences of many in today’s job market, in which the precarity of employment can create a cycle of moving back and forth between periods of paid work and reliance on benefits.