Do the lives of poets matter? It’s a debate that has raged since the middle of last century. In Philip Larkin’s day, the scholarly advocates of New Criticism felt that the text itself, regardless of authorial intent or audience affect, was all that really counted.

But we’re surrounded by the paratext – material such as covers, blurbs, biographies and introductions, which surrounds any text. We’re steeped in literary knowledge impossible to ignore. Can we interpret the demise of Helen Burns in Jane Eyre without acknowledging the Brontës’ history of consumption? Can we read Keats in ignorance of his similar fate? And might we enjoy the poetry of Larkin innocent of any knowledge of the poet’s outmoded beliefs?

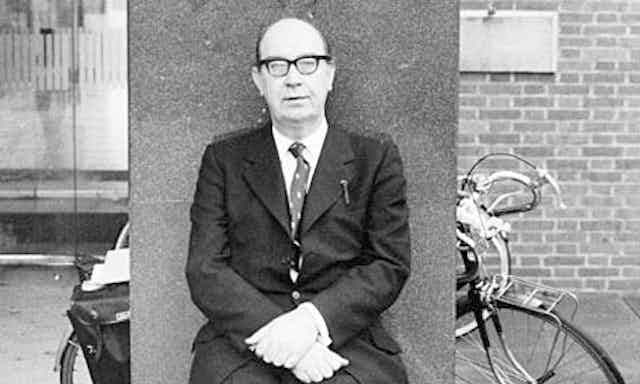

The University of Hull has just launched a major exhibition charting Larkin’s life, as part of Hull City of Culture 2017. This retrospective offers a measure of the man: his Beatrix Potter porcelains jostle for attention with his Billy Bunter books and his records (Handel, Dylan, Bechet, Holiday and the rest). His neckties, tattered and stained sit alongside his Grim Reaper cufflinks and his RSPCA pin. His D.H. Lawrence mug and matching T-shirt (in its original cellophane), his unwrapped packs of Christmas cards, a paperweight, a commemorative plate, his jazz journals and jazz catalogues. And there are oh-so-many books: How to Avoid Matrimony, Martin Amis’s Money, the diaries of Samuel Pepys, the four slim volumes of his own verse – and hundreds more texts, battered but beloved. All brought together, for all the world to see, in the place he once worked, the detritus of a half-lived life.

The show’s curator Anna Farthing told the BBC: “It’s incredible that somebody who had such a contradictory and conflicted world and life managed to produce art that was so clean and clear.”

Larkin’s poetry, though avowedly lucid, remains complex and conflicted. His attitudes to race, for example, maintained a precarious suspension between an inherited xenophobia (his father was a Nazi sympathiser) and a love of jazz. In All What Jazz, his collection of journalistic love-letters to the music which enriched his life, he supposed that slavery and segregation generated that music. The African-American, wrote Larkin “did not have the blues because he was naturally melancholy [but] because he was cheated and bullied and starved”. He warned that, if this oppression ended, its wonderful and strange fruit would perish too.

Larkin’s argument, though profoundly offensive, at least lacks hypocrisy. In his own life he appeared similarly determined to pursue (and enjoy) his miseries in order to provide an authentic foundation for the agonisingly slow processes of his art. This groundedness averted what he considered the pretensions of modernism. And so he was grudgingly content to spend 30 years running the university library at Hull – “it forces you to think about something other than yourself”, he told fellow poet John Betjeman in a 1964 documentary. It was good for him “as a poet”.

Miserable old so-and-so

Ten years earlier he’d lamented having let that “toad work squat on [his] life”. But by 1962 he’d come to see those daily labours as conferring meaning upon his existence: “Give me your arm, old toad; Help me down Cemetery Road.” As Andrew Motion suggests in his biography of the poet, Larkin seemed even to select his holiday destinations so as to enjoy own irritation at their discomforts and inconveniences: “As Larkin’s temper rose so his pleasure increased.”

But Larkin’s work (like Samuel Beckett’s) propagates redeeming ironies in its confrontations with the fear and loathing of everyday life, finding consolation in the commonality of its desperation, of that “sure extinction that we travel to”. We have far more in common than that which divides us. The value of this message is reinforced when echoed by this most unsentimental and divisive of literary voices: “What will survive of us is love.”

Larkin’s attitudes to women, meanwhile, seemed puerile, submissive, dismissive, adoring and sometimes aggressive. Yet he appears closer to Alfred Hitchcock than to Donald Trump. His work forces inner conflicts into the light of conscious scrutiny. It performs the opposite of the chauvinistic brag; he’s a constant voyeur, as once joyful and ashamed, into others’ sexual exploits: their “brilliant breaking of the bank” - “this,” he admits, “is paradise”.

Terry Eagleton once denounced Larkin as a “miserable old so-and-so who raised boredom, emptiness and futility to a fine art”. Yet Eagleton has also suggested that the progressive power of literature can run counter to the “overtly reactionary” intentions of its author.

Might we witness this in the fertile paradoxes which underpin Larkin’s verse? Might his playing out of such stresses illuminate contemporary cultural tensions? Such a re-revisionist approach might not only resurrect Larkin’s reputation, but see his work’s worth as founded upon its conflicted responses to his own hatreds and neuroses.

“Books are a load of crap”, Larkin wrote in his all-deprecating way. Yet his work demonstrates that literature’s value may lie in this very crappiness. Great poetry can be conflicted and inconsistent, can (as American poet Walt Whitman would say) contradict itself. The best sense, then, we may hope to find here would be just those words which are “not untrue and not unkind”. That may not be much, but it may also be enough.