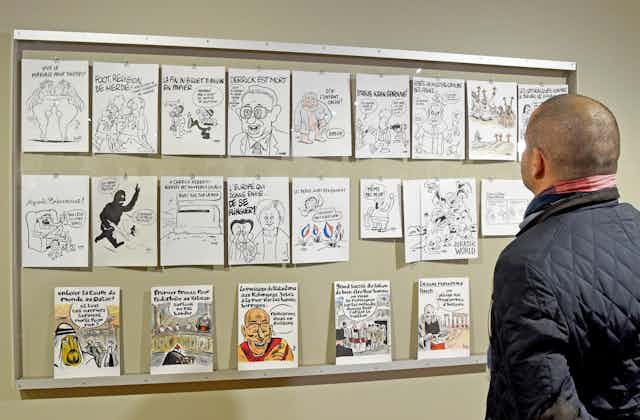

The cartoons in French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo offended many people. And as a result of the terrible actions taken by a handful of those people who took offence, which resulted in the murder of 12 people, Charlie Hebdo has become a case study for the significance and meaning of “offensiveness”.

On the one hand are those who champion free speech, who argue that we all have the right (some say, the duty) to express sometimes unpopular opinions without fear of censure. On the other are those who say that with that right comes a responsibility not to needlessly offend. For many who take this latter viewpoint, mocking religious symbols of two religions equally may seem equivalent on paper. But if one of those religions links to a culture, and very often an ethnicity, that already faces widespread discrimination and hardship, then perhaps free speech has crossed the line into offensiveness.

Some people are hard to shock – while others are offended when watching Big Brother or Little Britain. For our forthcoming book, Provocative Screens, we spoke to about 90 adults in the UK and Germany and found that people’s expectations of broadcasters and regulators – Ofcom in the UK and the state media authorities, “Landesmedienanstalten”, in Germany – is similar in both countries. People are generally optimistic that regulators and broadcasters feel the responsibility to protect more “vulnerable” audience members, such as children – but they do want greater clarity and communication when making complaints.

Audiences believed that broadcasters and regulators should be responsible for enforcing standards – but were largely unclear as to where the role of one ended and the other began. They also, perhaps as expected, believed different standards applied to public service broadcasters – who, they said, “cannot be allowed to get away with sanctioning a world view that is damaging” – and privately-owned media organisations and the internet, who have different priorities and “wouldn’t want people to turn off their channels”.

Expectations also differed depending on the genre of the programme. So a throwaway comment – that “Baghdad-style violence” had come to Britain – at the end of a commercial news clip reporting the Lee Rigby murder angered audiences more than racial stereotypes in a South Park episode.

Similarly, different speakers were held to different standards: so whether a joke about a vulnerable or maligned person or group was offensive depended greatly on who was telling the joke. People were prepared to forgive Matt Lucas when he lampooned “the only gay in the village” in comedy show Little Britain, for example, because Lucas is himself gay.

People’s attitudes towards free speech also depended greatly on their age – older audiences were easier to offend than younger people. One of the younger people we spoke to told us there should be no limits on free speech, “because artistic freedom is important” and that “censorship gets quickly out of hand. Who has the authority to draw the line?”

Great responsibility

Given that the giving and taking of offence is seemingly so subjective, whose job should it be to regulate the media? And where should the line be drawn? The murder of Charlie Hebdo journalists for daring to mock Allah has muddled a much-needed conversation that was going on in academic circles about the power imbalances between the subjects of jokes and those making them.

As media academics Peter Lunt and Sonia Livingstone discussed in their 2011 study, Media Regulation: Governance and the Interests of Citizens and Consumers, the question can be a minefield. Not just because different people have different perspectives and expectations, but quite simply because “offensive” and “offence” mean different things to different people.

The umbrella of “harmful and offensive material” needs more nuanced, focused and critical research. It is going to need widespread multicultural and inter-generational interaction with a diverse cross-section of the public to build a better understanding than exists now. Our recent fieldwork has shown us that, contrary to what we expected, swear words, bad language, inaccurate facts – the sorts of things that are regularly reported to Ofcom – were not always what people wanted to talk to us about. Rather, they were concerned with wider issues around the construction of characters or the relative power and positions of the actors or the creators behind the characters.

If we are not careful, these concerns are all-too easily brushed away as individual, aesthetic, cultural or political sensibilities. But without understanding offence properly, we are stranded at the level of policing bad language. So the moment is right to go beyond such “obvious” triggers and to provide a more nuanced understanding of what it means to be offensive.