The High Court has ruled that the body of Moors murderer Ian Brady should not be disposed of in the way that he was said to have wanted. This is the latest legal battle to have punctuated the life, and death, of Brady, who tortured and murdered five children between 1963 and 1965.

Brady died in a secure hospital in May not far from where he committed his crimes. He left a will naming his solicitor Robin Makin as his executor. Since then Brady’s body has remained refrigerated. The local authorities, Oldham and Tameside councils, requested assurances from Makin that Brady’s ashes would not be scattered in those areas. Given the proximity to the site of Brady’s crimes, this would have been deeply offensive to the victim’s families and the wider public. Sefton, where the hospital is located, also asked for details of Makin’s plans.

Media outlets suggested that Brady wanted his ashes scattered in his childhood town, Glasgow. But the local council there, and private crematoria in the area, said they would also refuse. It was also reported that Brady requested that Hector Berlioz’s haunting composition, Symphonie Fantastique, be played during the cremation – a request declined by the judge, who said: “It was not suggested by Mr Makin that the deceased had requested any other music to be played or any other ceremony to be performed and, in those circumstances, I propose to direct that there be no music and no ceremony.”

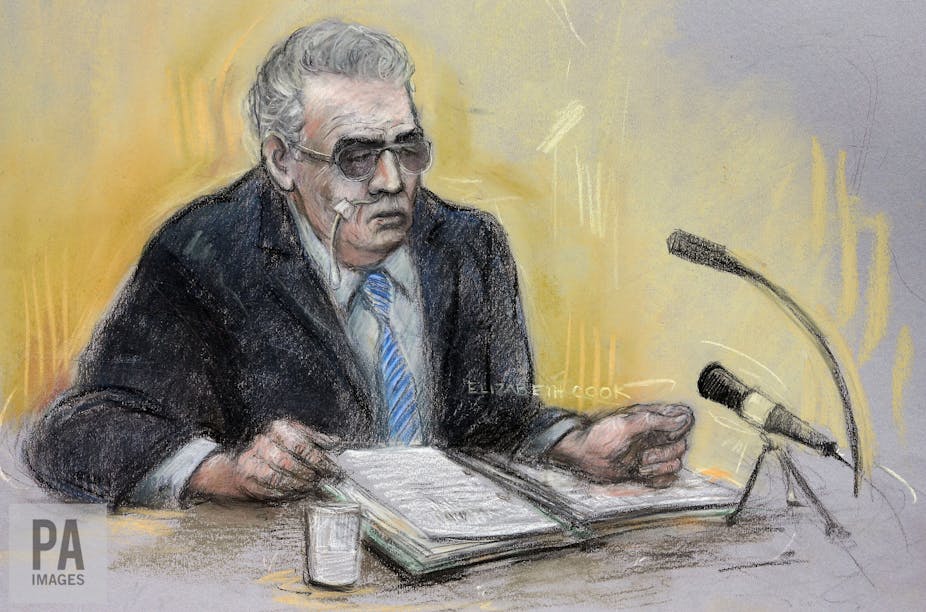

Makin hasn’t disclosed his plans for Brady’s body, although he told the coroner’s officer that there was “no likelihood” of the ashes being scattered on Saddleworth Moor, where Brady buried his victims. Makin argued that the persistent demands for detailed assurances had prevented him from disposing of the body.

The living trump the dead

It’s easy to understand why Oldham and Tameside were keen to ensure that Brady, in any form, did not touch their ground. Brady’s body is contaminated by his crimes. Brady the person and Brady the body, or indeed ashes, are considered inseparable.

This was especially important as one of the victims, Keith Bennett, has never been found. Indeed, in an unusual turn, the coroner, Christopher Sumner, himself sought similar assurances from Makin at the inquest into Brady’s death.

What many may not realise is that our wishes for the disposal of our bodies have moral, but very little legal, strength. The law simply assigns the duty to ensure that a body is lawfully and decently disposed of. We cannot bind the living to do it a particular way, in a certain place or with certain music. As Muireann Quigley and I have demonstrated, the legal test is a circular one – a disposal is generally lawful if it is decent, and decent if it is lawful.

While it may be the norm for these decisions to fall to an executor, the courts can invoke s116 of the Senior Courts Act 1981 to appoint an alternative administrator where “special circumstances” demand this. In Brady’s case, Geoffrey Voss the judge said these circumstances included that Brady was “uniquely evil” and the concern that there would be significant public opposition if a ceremony were allowed to go ahead. Given that the parties involved couldn’t agree on the particulars, the court assumed the duty to dispose of Brady’s remains instead of allowing his solicitor to remain in charge.

The court also decided that it has jurisdiction to determine the details of the disposal. Voss said: “The deceased’s wishes are relevant, but they do not outweigh the need to avoid justified public indignation and actual unrest.”

Makin’s representative argued that this was an effort to covertly reintroduce the old practice of demanding that the bodies of executed convicts were buried in prison grounds. While there seems to be little mileage in this submission, it could be argued that refusing to give effect to the antemortem wishes of the dead could be used as a form of posthumous punishment.

Not too long ago, gibbeting and public dissection were mandated after the execution of convicted murderers. Given the strength of the religious doctrine that bodies be buried whole, this was intended to be both additional punishment and deterrence. Sentences involving post-execution humiliation still endure elsewhere. No doubt many would argue that Brady deserved for his body to be treated with contempt.

It has not been suggested that Brady’s body be anything other than lawfully and decently disposed of. Yet what happens to Brady’s body is hugely symbolic. When, like Brady, someone does things in life that so profoundly impact upon the wider public, it is to be expected that after death, the needs and views of the living will trump all. So, there will be no music. Nor will there be a ceremony. And the courts have intervened to ensure that Brady, in death, can do no further harm.