The relationship between landscape and English national identity goes back at least to the 18th century, when aficionados of the picturesque and the sublime made places such as the Lake District objects of patriotic pride even before Wordsworth declared them “a sort of national property”. Today, links between landscape and nation are charged with new significance in the context of debates about Brexit and Scottish independence. The nature of Englishness has never been more topical.

But what, exactly, can landscape tell us about Englishness? This was the question I explored in my new book, Storied Ground. In order to do so, I looked at a number of particular case studies. Here are three of them:

The cliffs of Dover

In a recent speech, Boris Johnson claimed that Brexit was “not some great V-sign from the cliffs of Dover”. Whether or not you were wooed by his words, the foreign secretary’s choice of image is telling. The cliffs of Dover are powerful symbols of the nation, and specifically its insular character.

Surmounted by an ancient castle, they have long been associated with defence and defiance: metaphorically as well as physically, they are ramparts, keeping out the rest of the world. Across the 19th and 20th centuries, the cliffs were described as “white walls”, as “natural defences”; in 1878, Black’s Guide to Kent called Dover a “fitting symbol of English Power”, with “its walls of glittering chalk, majestic and impregnable”.

In a more peaceable vein, the cliffs have also functioned as markers of home – familiar, historic, reassuringly unchanging. But something like the V-sign has persisted throughout. When the French European Commission president, Jacques Delors, announced his plans for European unity in autumn 1990, The Sun told its readers “to face France and yell ‘Up Yours, Delors’”. And where better to “bawl at Gaul”, the paper suggested, than from the cliffs of Dover?

Indeed, page three on November 1 that year featured no underdressed young lady, but a portly bearded man in a hat and black leather jacket, draped in a Union flag, holding a half-drunk pint of beer and shouting out at France while sitting atop Dover cliffs.

The Scottish border

As The Sun’s injunction to what it called “true blue Brits” suggested, the patriotism associated with the white cliffs is British as well as English. This is true of other English landscapes, one notable example being that of the Northumbrian border with Scotland.

Here, the history of conflict between the two nations is indelibly inscribed in the landscape, with its ruined castles and blood-soaked battlefields. Yet, for much of the 19th and 20th centuries, this environmental heritage of enmity supported a form of Englishness quite different from any stereotypical ideal of pastoral, cottagey tranquillity. This was a grittier Englishness — one of romance, valour and derring-do; but it was not one that cast the Scots as a national “other” in any very antagonistic sense. Instead, in concert with a complementary variant of Scottishness, it conscripted the divisions of the past into the service of unionism. It was, to use the historian Graeme Morton’s helpful term, a variety of “unionist-nationalism”.

Take Flodden Field, site of the terrible Scottish defeat of 1513, which was reimagined as a place of “splendid past bravery and present unity”. There, in 1910, an Anglo-Scots committee erected a great cross, hewn from Aberdeen granite and dedicated “to the brave of both nations” who had fallen on that bleak Northumbrian moor. The cross stands there still. Today it also memorialises the unionist identities now in retreat on both sides of the border.

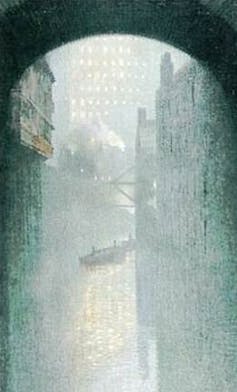

Manchester: shock cityscape

The historian Asa Briggs has called Manchester the “shock city” of the Victorian age. Its landscape of “dark, satanic mills” is often contrasted with a supposedly dominant, countrified ideal of Englishness: as the sociologist Krishan Kumar has said, by the 1880s “the essential England was rural”.

But was it? Manchester suggests otherwise, or at any rate that landscapes of industry and commerce were integral to the geography of Englishness. Throughout its Victorian and Edwardian heyday, Manchester’s architecture of enterprise was aestheticised by artists and a focus of both tourist interest and local pride.

Bradshaw’s famous railway handbook reckoned a visit to a factory was “one of the chief sights” of the place. The city’s warehouses were said “to rival in architecture the palaces of Venice”, and its public buildings were acclaimed as powerful emblems of the national importance of the metropolis of cotton. In the landscape of Manchester could be read the story of the nation’s rise to economic greatness, and as such — as one observer noted in 1900 — it was “a microcosm of England”.

These three examples illustrate how Englishness has been found in diverse places and has taken diverse forms — urban as well as rural, northern as well as southern. Indeed, this very diversity has been a major source of the integrity and resilience of English national identity — and indeed of the English nation — throughout modern history.

And so whatever side Britons might choose to take on Brexit or the issue of Scottish independence, they would do well to remember that.