Effective law enforcement requires the support of the community. Such support will not be present when a substantial segment of the community feels threatened by the police and regards the police as an occupying force.

These words could be read as a comment on the recent shootings in Dallas, Texas. Or on the deaths of Alton Sterling, in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and Philando Castile in St Paul, Minnesota, who last week became the latest casualties on the tragically long and ever-growing list of African-Americans killed by white police officers.

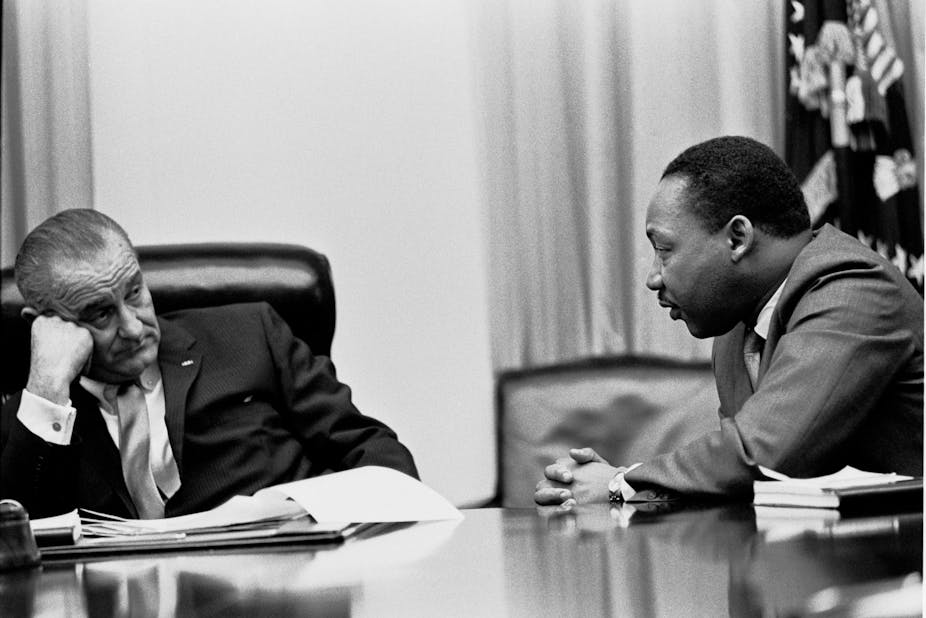

But they actually come from the late 1960s, and specifically from the Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders. The Kerner Commission, as it is better known, was set up by President Lyndon Johnson, who tasked it with identifying the causes of the race riots that took place across the US in the five “Long Hot Summers” of 1964-68.

The report found a history of poor police practices was a common factor in many riots. And five decades on, it seems not much has changed.

In 2015, the report of President Obama’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing made the same point: “Law enforcement cannot build community trust if it is seen as an occupying force coming in from outside to impose control on the community.”

Among other things, the task force looked to new technology to provide a solution for old problems. It recommended that police officers wear body cameras to help with training and improve public trust. They should also carry tasers as well as guns.

It sounds like common sense. If officers are filmed while they are on duty then they will think twice before stepping out of line; and using tasers to stop violent suspects will lead to fewer fatal shootings. But it’s not that simple.

Unintended consequences

Body cameras don’t come cheap. The Dallas Police Department has spent millions of dollars on new cameras, but so far has only been able to kit out about 400 of its 2,500 officers.

And that’s just the start. Scrutinising the thousands of hours of footage generated every week means that many officers spend most of their time at the desk rather than out on patrol.

Cameras could also make things worse, not better. Some people stopped by the police will not like being filmed, making a difficult situation more tense. There is also a question of civil liberties. In August last year, the police union in New York sparked controversy by calling on officers to take photos of the 75,000 homeless people in the city to draw attention to “quality of life” offences.

Then there are tasers, which the 2015 task force report refers to as “Conductive Energy Devices” – a nice technical term that makes them sound harmless.

If only. A 2014 US Department of Justice report on the police department in Cleveland, Ohio described the use of tasers. The electric current “instantly overrides the central nervous system, paralyzing the muscles throughout the body, rendering the target limp and helpless” and inflicting “excruciating pain”.

And that’s just in healthy adults. For the very young, the elderly or infirm it could be even worse; anyone tasered falls straight to the ground, so there is a risk of serious injury or even death.

The Cleveland Report also found widespread evidence of police abuse in the use of tasers. This included tasering a “suicidal deaf man who committed no crime, posed minimal risk to officers and may not have understood officers’ commands”. Another suspect was tasered while strapped to a stretcher in the back of an ambulance.

Most police officers do not abuse the trust placed in them in this way. They risk their lives on a daily basis for the public good, as was shown all too clearly in Dallas. It is important that police officers are given the support they need to do their job. State-of-the-art resources are a part of that – but they’re not a quick fix for deep seated policing problems.

Long past time

Back in 1968, the Kerner Commission called for changes of a different kind. They included better training and clearer policy guidelines for police officers, simpler and more effective complaints procedures for ordinary citizens, and more community policing. The commission also highlighted the need to recruit more black police officers to work in African-American communities.

A lot has changed since the 1960s, but some things remain the same. Good policing is about people. Police officers working with the communities they serve to make a better and safer society for everyone.

Today, police forces across America still fail to recruit from minority groups. In too many towns and cities, police patrols are seen as nothing short of an occupying force.

In its day, the Kerner Commission’s recommendations were largely ignored. 50 years on, it’s high time they were finally put into practice.