Turkish citizens went to the polls on March 31 to elect their mayors and local officials.

The last regional elections were held on March 30 2014 and resulted in the victory of the governing Justice and Development Party (AKP), which won 43% of the votes. While this year’s elections once again marked a victory for the AKP, with the AKP-MHP (Nationalist Movement Party) alliance taking 51.6% of the vote, it also shook the foundations of the AKP’s enduring rule. A significant breakthrough by made by the opposition alliance, CHP (Republican People’s Party) and the Good Party (İP), which took control of big cities like Istanbul, Ankara, Izmir, Adana, Antalya and Mersin.

37 women mayors

What is also significant this year is that 37 women mayors were elected, with 24 from the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP). An additional 34 women co-mayors will also run for office, albeit unofficially, through the co-presidency system implemented by the HDP, entailing a joint male-female presidency.

This is a rare victory given that women are make up only 17% of the Turkish Grand National Assembly and that women’s regional representation in Turkey remains marginal at less than 3%. Political parties across the Turkish political landscape have long been resistant to women taking part in politics. Among the 2019 municipal candidates, only 7.89% were women, and of metropolitan municipal candidates, of whom only 10.8% were women.

Yet the pro-Kurdish HDP led the way with a 50/50 gender-balanced candidate list. It was an uncommon phenomena as the list of Erdoğan’s AKP had only 1,25% women and the main opposition party, the Republican People’s Party (CHP), did little better – its list had just 5.23% women. While women’s representation remained just 2,66% at the local level, it thrived in the pro-Kurdish municipalities.

An efficient gender quota

This success of women’s representation is largely due to the HDP’s gender quota, mandating alternations of women and men on party lists and leadership. Inspired by the German Greens, the system was first applied in 2005 by the pro-Kurdish Peace and Democracy Party (DTP) for the party leadership only and then enlarged during the 2014 local elections.

In 2014, for the first time in the DTP’s history as well as in the history of Turkey, the party campaigned for female and male co-mayors across its municipal candidates lists. It stated:

“The enlargement of the co-presidency system and its implementation in municipalities will be a step to widen the political space for women. As far as is known, there is no country which implements co-presidency system at municipal level. In this context, Turkey will also have the opportunity to make a pioneering change in opportunity structures that will serve as a model to the rest of the world.”

Parity in Kurdish municipalities

As the successor to the DTP, the HDP has committed to the co-mayorship system despite pressures from the government. The system faced legal opposition on the grounds that it violates the Law on Municipalities, which allowed the government to crack down on co-mayors in 2016.

Despite the political pressure, Kurdish municipalities embraced the practice, albeit unofficially. All municipalities held by the pro-Kurdish party as a result of 2014 local elections were run by co-mayors. Despite the fact that co-presidency of leadership has been applied elsewhere, co-mayorship has been unique to the pro-Kurdish parties in Turkey.

While the HDP is not officially allowed to assign co-mayors to its list due to legal restrictions – only one candidate is allowed for one rank – the party campaigned for co-mayors. Now that the party has won 58 municipalities, 24 of which were won by women candidates, all will be run under a joint presidency of man and woman.

Women are under-represented across the world

Last two decades have witnessed a gradual increase in women’s political participation across the world. The proportion of seats held by women in national parliaments worldwide rose from 13% in 1998 to 24% in 2019.

Yet women are still under-represented across the world and excluded from equally participating in politics. Regionally, the Americas lead the way, with women’s representation with 30.6% thanks to widespread application of gender quotas in South America. Women’s representation in Europe is 28.6%, followed by sub-Saharan Africa at 23.9%, Asia with 19.9%, the Arab States with 19%, and the Pacific with 16.3%.

While representation in the higher instances of politics remains a challenge, scholars argue that women are better represented at the local (municipal) level.

Lower campaign costs and smaller financial hurdles, less arduous time commitments and travel requirements could improve women participation as well as the perception that women are more interested in the “local” issues than by other levels of government.

Contradictory results

This hypothesis has been difficult to test in the absence of regular documentation worldwide. Nevertheless, insofar the data shows some contradictory results.

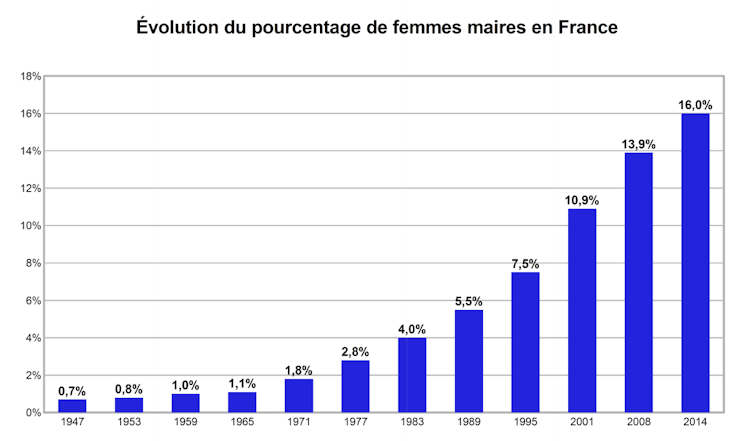

In 2013, among 28 European Union countries, only 14% of mayors or other municipal leaders were women. In France, 84% of mayors are men.

Whereas in the United States, as of 2019, only 20.9% of mayors in cities with populations over 30,000 were women.

Why more women is needed in politics?

Women’s under-representation in politics reveals a significant democratic deficit worldwide. Experts argue that women’s inclusion in politics would consolidate democracy and ensure women-friendly policy-making, addressing women’s needs and policy concerns. A 2006 study indicated that as the number of women in politics increase, the more women’s voices are heard.

With this objective, today along with national governments, many international organisations, from the European Union to the African Union, are working to increase women’s political participation.

However, discriminatory attitudes and practices as well as gender bias in political recruitment and promotion continue, preventing women’s access higher positions.

Targeting a real egalitarian democracy?

The pro-Kurdish party aims to promote women in politics, while at the same time, democratise and decentralise the monopolist and male-dominant power structure within Turkey’s political institutions. It thus contrasts sharply with the highly masculinised politics in the country and also the region.

By including women in local governance, pro-Kurdish municipalities worked in close cooperation with women’s groups and civil society to address issues like violence against women, access to labour market and education at the local level.

Beyond the symbolic importance of having a prominent woman figure in city affairs and gender-sensitive policy making, the co-mayorship has also been effective in increasing women’s participation in and aspiration for local governance. By promoting women to co-mayorship, the measure also breaks the glass ceiling, which prevents women from advancing in their political careers at the local level.

Despite all these advantages, today parity in Kurdish municipalities is not well institutionalised due to legal restrictions and political opposition.

Further research is needed to observe the power dynamics of co-presidency measure, as applied at the party leadership and/or municipal level. Nonetheless, the application may still serve as an example for other parts of the world to foster women’s representation in local governance not only in policy-making, but also in decision-making.