The political saga triggered by the special counsel investigation into Donald Trump, which has cast such a long shadow over his presidency, will continue long after the inquiry’s end.

According to U.S. Attorney General William Barr, prosecutor Robert Mueller determined that Trump’s campaign did not collude with Russia to influence the 2016 presidential election. The special counsel did not make a conclusion about whether Trump committed obstruction of justice.

Because Barr has not made Mueller’s more than 300-page report public, his exact findings remain unknown. Congressional Democrats are demanding access to the full report by April 2 to see what Mueller uncovered during his 22-month investigation into the president.

As this federal probe turns into a partisan battle, here are four key threads our experts have been watching.

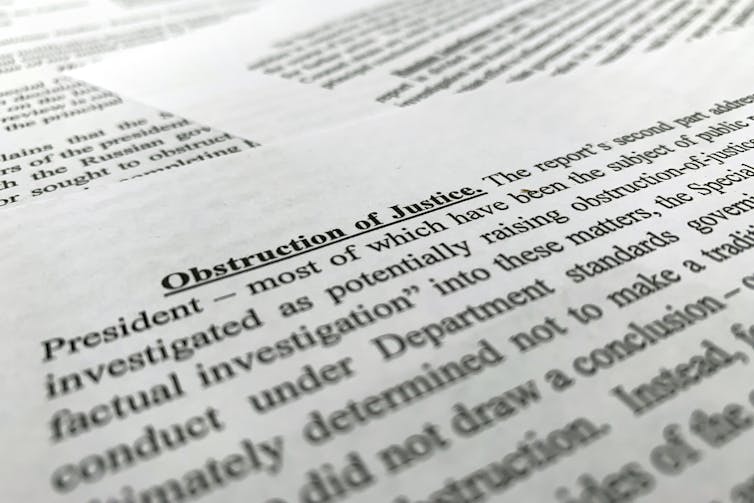

1. Obstruction of justice

In a March 24 letter to Congress summarizing Mueller’s findings, Barr wrote that the evidence collected is “not sufficient to establish that the President committed an obstruction-of-justice offense.”

That differs from Mueller’s conclusion. He wrote that “while this report does not conclude that the president committed a crime, it also does not exonerate him.”

How can two people draw different conclusions from the same evidence?

“Obstruction of justice is a complicated matter,” writes law professor David Orentlicher of the University of Nevada-Las Vegas.

According to federal law, obstruction occurs when a person tries to impede or influence a trial, investigation or other official proceeding with threats or corrupt intent.

“Bribing a judge and destroying evidence are classic examples of this crime,” Orentlicher says.

But other actions may constitute obstruction too, depending on the context. And some actions that look like obstruction may not be, because the law requires a “corrupt” intention to obstruct justice as well.

President Trump did many things that influenced federal investigations into him and his aides, Orentlicher points out, including firing FBI Director James Comey and publicly attacking the special counsel’s work.

The legal question is: Did he do so with “corrupt” intent?

2. Release of the report

That’s among the many things House Democrats hope to learn from reading Mueller’s report.

But they may never see it, writes Charles Tiefer, professor of law at the University of Baltimore. He expects Trump and Barr will do “everything in their power to keep secret the full report and, equally important, the materials underlying the report.”

Tiefer was special deputy chief counsel of the House Iran-contra Investigation in the 1980s and has worked on many major House investigations.

“I saw the tricks the executive branch can pull to withhold evidence,” he says.

The main legal grounds Barr and Trump will try to use for suppressing the Mueller report, according to Tiefer, are executive privilege and grand jury secrecy.

Trump is likely to argue that executive privilege – the principle that the president can withhold certain information from the courts, Congress or others – permits him to keep much of the Mueller report private.

Executive privilege cannot be used to shield evidence of crime. But that’s where Barr’s exoneration of Trump really helps the White House, Tiefer says.

The attorney general, for his part, has already invoked grand jury secrecy – the rule that attorneys, jurors and others “must not disclose a matter occurring before the grand jury” – to keep Mueller’s report private.

Tiefer suspects Barr will seek to maximize what’s the law by using “the much-deprecated ‘Midas touch’ doctrine,” which could bury “everything indirectly and remotely having some attenuated whiff of a grand jury” as protected information.

3. Politics versus the law

In demanding Mueller’s full report, Democrats have asserted that Barr cannot be trusted to interpret its findings objectively because he was appointed by the president. They say that makes his exoneration of Trump a political, rather than legal, determination.

The question of Barr’s independence first arose during his confirmation hearing in February.

Barr, a veteran lawyer who previously served as President George H.W. Bush’s attorney general, interprets the Constitution as giving the president almost unlimited power. He has referred to the attorney general – the government’s top prosecutor – as “the president’s lawyer.”

The question of who the attorney general works for dates back centuries, says Austin Sarat, a political scientist at Amherst College. That’s because the position is not mentioned in the Constitution.

“It was created when the First Congress passed the Judiciary Act of 1789,” Sarat writes.

That law called for the appointment of a person “learned in the law, to act as attorney general for the United States.” It laid out such limited duties for the role that “the attorney general was to be a part-time official” reporting to the president, Sarat says.

As a result, “Throughout American history, there have been different visions of the role of the attorney general and his or her relationship to the president,” he adds.

4. Loyalty to the president

Trump expects personal loyalty from his staff – including from his attorney general – reports Yu Ouyang, professor of political science at Purdue University Northwest.

The president fired the previous attorney general, Jeff Sessions, in November 2017, reportedly because Sessions’ recused himself from overseeing the FBI’s probe into Russian meddling – a betrayal that opened the door for Mueller’s appointment as special counsel. That’s how Barr got the attorney general job.

Ouyang, who studies loyalty and politics, says presidents it’s normal for presidents to prefer loyalists.

“Loyalty comes in handy for presidents when they enter office and ask, ‘How do I select the people who will help carry out my agenda?’”

What sets Trump apart, for Ouyang, is his “exceptional emphasis on loyalty.” He values it over other critical qualities like competence and honesty. And he appoints his staff accordingly.

That, say Democratic lawmakers, is why Barr cannot be the only public official to see the evidence Mueller collected on Trump.

This article is a round-up of stories from The Conversation’s archive.