When they each ran significant chunks of the Australian mining industry in the 1970s, the late titans Sir George Fisher and Sir Maurice Mawby were often dismayed at the attacks politicians, and others made on the resources sector.

Caught up in debates about their industry’s approach to Aboriginal land, the environmental damage mining caused and its contribution to the economy, Fisher and Mawby could not fathom why their good works in building a vibrant export industry were little understood, and appeared to be unappreciated. Yet their responses were most often delivered in the way of the times: quiet lobbying of politicians and bureaucrats.

This approach changed dramatically in the mid-70s when younger successors like Rod Carnegie and Hugh Morgan reacted to the Whitlam Government’s proposed resources rent tax, and the Prime Minister’s claim that the mining industry was majority foreign owned.

The industry challenged the claim publicly, it engaged an external consultant to compile an annual report on the sector’s value to the economy, and ran an extensive television advertising campaign promoting mining as the “backbone of the country”.

It all sounds so familiar, doesn’t it?

Wedge politics

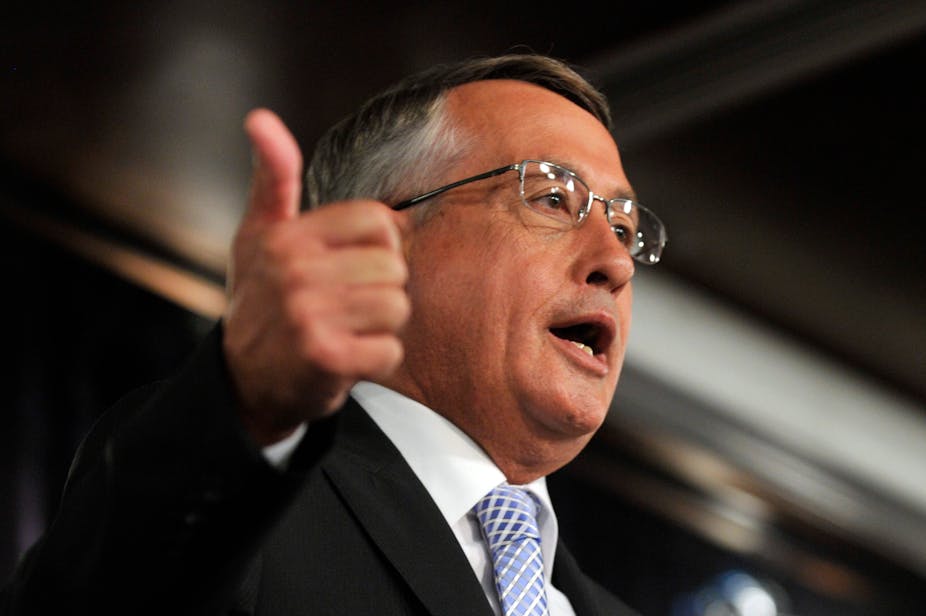

Wayne Swan’s “fair go” foray into Labor’s decades-long stoush with the resources industry has generated a public reaction from mining leaders that Fisher and Mawby would not have contemplated. No-one any longer doubts the sector’s contribution, but this time the stoush has become personal.

In one of his Sceptical Essays, British philosopher Betrand Russell wrote that wherever party politics exist, politicians appeal primarily to one section of the community while their opponents appeal to another. The politician’s success, he wrote, “depends on turning his section into a majority”.

Swan’s vehement use of the “fair go” message seems to designed to rouse passions in his supporters and to generate a reaction from the Opposition on behalf of theirs: billionaire miners. Here is the classic wedge of modern politics.

Dissecting the ‘fair go’

Selecting messages for any strategic communication involves using words that resonate with people who are either directly affected by an issue, or can influence others. In this case, the message works in both dimensions, whether Mr Swan and his media advisers intended it or not.

First, voters. At a time when support for federal Labor is becalmed at best, the message can strategically refocus impressions of the government by signifying that it still champions working people. Voters thus become the primary target for the message, which is fairly simple. The government reckons you ought to get more out of the mining boom than you do now and the only reason you are not is because a small number of billionaires is trying to stop us. It’s time for that good old Aussie notion of a “fair go”.

Second, the media. Communication strategists hold that the mass news media’s choices about what it covers influences what the rest of us think about. Sometimes journalists think their opinions actually influence ours.

But nothing is guaranteed when journalists at all levels “mediate” messages before the intended audience reads, understands and accepts them and, hopefully, takes action. Journalists are rarely the primary audience for strategic messages, but almost always play the role of porters carrying the luggage influencing what we think about. The treasurer’s strategy has been clever. His simple idiomatic message is designed to appeal to voters at the same time he is running a more complicated line about policy influence.

Power plays

For eons people with money and political connections have attempted to influence policy. It’s called lobbying. In this case, the Treasurer is arguing that lobbying has gone too far and that ordinary voters aren’t getting a “fair go” because a few billionaires are spending up big.

There’s a link here with criticism of the theory that communication between an organisation and its “publics” should be symmetrical, that is equal and based on a transparent discourse that leads to changes in policy.

Critical scholars argue this is impossible, because power relationships are unequal. Mr Swan’s argument illustrates the point: mining billionaires have more money, therefore they can exert more influence than voters, so it’s time for a “fair go”.

This of course begs a question about the government’s own power, influence and resources. If its communication strategy works, it doesn’t need to spend voters’ money on messaging. The force of the “fair go” message will demonstrate its power and influence.

Perhaps that was Russell’s point when he wrote that a politician’s special skill lies in both knowing which “passions can be easily aroused”, and in preventing those passions from harming the politician.