When it comes to women’s history in this country, most Canadians could use a refresher, according to a recent poll conducted by Historica Canada about the history of women in Canada. Media outlets like the Globe and Mail and Huffington Post picked up its findings and ran stories about how Canadians need to be more aware of their country’s historically significant women.

Historica Canada’s poll included topics that ranged from the “filles du roi” in New France to the 1985 revision of the Indian Act. But the Globe’s coverage of the poll focused only on white anglophone female artists in the 20th century.

By narrowly choosing the type of women to cover through history, we believe media outlets like the Globe — intentionally or not — suggest that these white 20th-century women were Canada’s only historically significant women.

We challenge this representation in media about women in history — there are far more women than the coverage implies. We also challenge the original poll that inspired the coverage in the first place.

Of the 12 questions asked by Historica Canada, only one ventured into the pre-20th century period. Nonetheless, one could argue that most of Canada’s most fascinating women lived before this time.

Why don’t we learn about the true history of women?

As women’s historians, we teach courses that expand on stories rarely told in the media, history books, lecture halls and classrooms. For example, Donica’s women’s history course at the University of Regina starts at the beginning of time. She introduces students to the story of Aataentsic, a woman in Wendat legend who falls from the sky and gives birth to humankind.

This course also features people like Madame de La Tour, an Acadian woman who died in 1645 defending her fort from rival French powers.

Esther Wheelwright was an English girl who lived with the Wabanaki and in 1760 became Mother Superior of the Quebec Ursulines.

And then there’s Isobel Gunn, a cross-dressing fur trader known as John Fubbister who canoed her way through the northwestern interior in 1806-07.

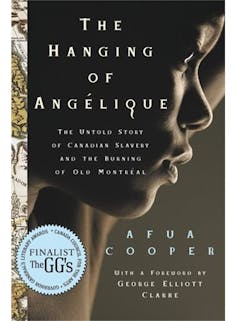

One could argue that the most “significant woman” in Canadian history is Marie-Josèphe dite Angélique, as historian Afua Cooper demonstrates in her riveting book, The Hanging of Angélique.

Angélique was an enslaved Black woman who lived in 18th century Montréal. She had three children, all of whom died in infancy. Several times, she spoke out against her employer’s cruelty.

Angélique made plans to return to Portugal; she also attempted, through an unsuccessful escape, to put that plan in motion. However, in 1734 the government of New France accused her of starting a fire that burned down half of the city.

Angélique was subsequently tried, tortured and executed. As the king’s scribe wrote: “She was hanged and strangled and then thrown into the fire, and her ashes were then thrown to the winds.” Students who learn about Angélique respond with incredulity. Why have they never heard about her?

Expanding our view of the past

Much work remains to be done. Certainly it is good to learn about writers and artists from the 20th century. Yet Canadian women’s history is far richer than just these women.

As historians of women, we work hard to bring this richness to the centre of public knowledge. Memory keepers in Canada have been working for decades, even centuries, to foreground women’s lives.

Elders offer teachings about such women as Thanadelthur, a Dene woman who brought peace to warring Cree and Dene nations during the early 1700s, as Lucy Antsanen explains.

Crucial, too, are such projects as the Alberta Labour History Institute’s Indigenous Labour series, featuring stories of hard-working women. Digital archives like Rise Up!, which reveal women’s activism, are also key.

Readers might further consult Merna Forster’s “100 Canadian Heroines” book series. The Great Unsolved Mysteries in Canadian History project showcases women’s history, as does Canada’s History’s women’s history webinar series and Historica Canada’s heritage minutes and guides.

How can we create a more expansive definition of who, and what, is historically significant?

As a start, we invite Historica Canada, the Globe and Mail and others to join us in sharing these stories. We also invite everyone to learn more about the histories of women they already know, whether they’re their mothers, grandmothers, aunties, sisters or friends.

It is time to bring these women’s stories into the mainstream. It is time to recognize the wealth of knowledge about Canada’s “most significant women” that we already have.