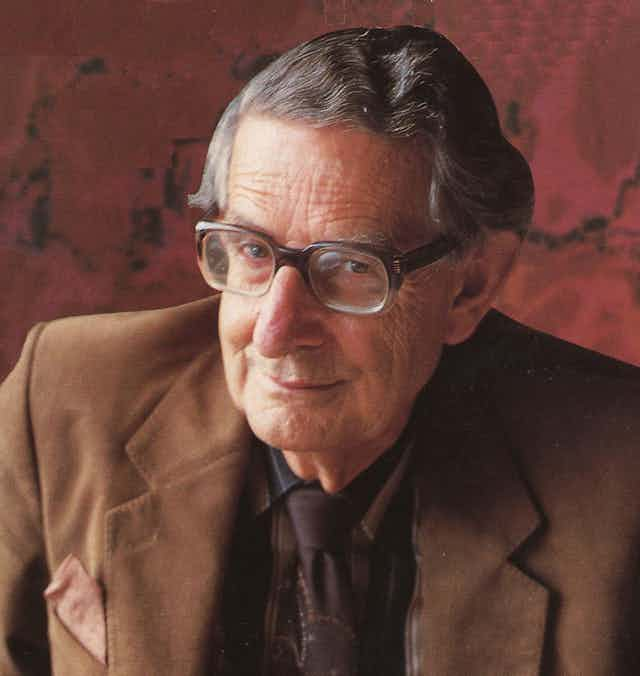

Exactly 70 years ago, in October 1947, Hans Eysenck (1916–97) was appointed to the Maudsley Medical School in south London (later the Institute of Psychiatry), where he spent his entire career.

He was Britain’s most prominent psychologist and among the world’s most highly cited researchers across all of the behavioural and social sciences. He was largely responsible for establishing clinical psychology in Britain and he developed one of the most influential theories of individual differences and personality and contributed to many other areas of psychological research.

He gained particular public notoriety through his controversial views on race and intelligence, which he summarised in an edgy two-part BBC debate in the 1970s. (He argued that, on average, black people in the US scored lower on IQ tests than white people and that the difference was largely due to genetic factors rather than cultural differences, relative poverty, inferior education, or any other non-genetic factors.)

Eysenck emigrated to the UK from Germany soon after the Nazis came to power in 1938. Throughout his life he denied strenuously that he was Jewish, but in his autobiography, published in 1997, long after he retired, he mentioned almost in passing that his maternal grandmother, who brought him up from early childhood, “came from a Jewish family” and died in a concentration camp in 1944.

In a review of his life and work in 2000, his close friend and devoted follower Arthur Jensen declared: “His only Jewish relatives were his stepfather and his second wife, Sybil.” This is simply untrue.

We have proved beyond doubt that Eysenck was in fact half Jewish on his mother’s side, and therefore strictly Jewish according to Rabbinic law (Halacha). Using techniques and resources of Jewish genealogy, we discovered that his maternal grandmother’s birth name was Helene Caro. We then located her marriage certificate, which confirmed that both Helene and her husband (Eysenck’s maternal grandfather) Max Werner belonged to long-established Jewish families.

Helene died in Theresienstadt concentration camp in 1944, and this is recorded in the Database of Victims of the Holocaust in Czechoslovakia and in one of the Stolpersteine (stumbling blocks) commemorating victims of the Holocaust in the streets of Berlin, where she lived.

Possible motives

So why did Eysenck keep his Jewish heritage such a secret for so long? Such concealment was extremely unusual among Jewish immigrants into the UK, and it is not easy to understand or explain. His denial provides an interesting case study that helps to throw light on the psychological problems faced by refugees who belong to persecuted ethnic groups.

Was he was anti-Semitic, in spite of being half Jewish? No; he was consistently pro-Semitic throughout his life: his closest school friends were Jews, he hired many Jews to work with him at the Institute of Psychiatry, and his second wife was Jewish. Did he consider himself non-Jewish because he was not religious and not a practising Jew? No; for most, being Jewish is a matter of ethnicity and descent rather than religious practice – and Eysenck himself described his second wife and several of his colleagues as Jewish although they too were non-religious and non-practising. Did he simply not know that his mother was Jewish? No; he lived with his Jewish grandmother until he was 18-years-old, and his son Michael told us that he was “100% certain” that his father knew that she was Jewish.

We suggest several more credible motives. As a Mischling (part-Jew) in Nazi Germany, he may have developed a habit that persisted after he emigrated of concealing his Jewish ancestry. When he arrived in the UK, anti-Semitism was quite widespread, and he may also have wished to play down his Jewish ancestry to avoid becoming a target. He may even have wished to avoid appearing to capitalise on his partly Jewish identity.

Given he was likely close to her it may well have been however that he felt remorse about having failed to rescue his beloved grandmother Helene from her ghastly fate. This would explain why he went to some lengths to conceal her identity in his autobiography. He wrote at length about her without ever mentioning her first name or her birth surname, and he used a false initial for her first name in the index. Perhaps he hoped to avoid anyone digging up the details, as we managed to do despite his concealment and misdirection. We shall never know for certain.

The curious case of Eysenck’s Jewish ancestry, although unusual in its specific details, may possibly be typical of more common psychological problems faced by migrants, especially those who belong to persecuted minorities. Migrants have difficulty assimilating into host cultures for many reasons. This is a particular problem when, as is often likely to be the case, they have had experiences in their home countries that they would prefer to forget about.