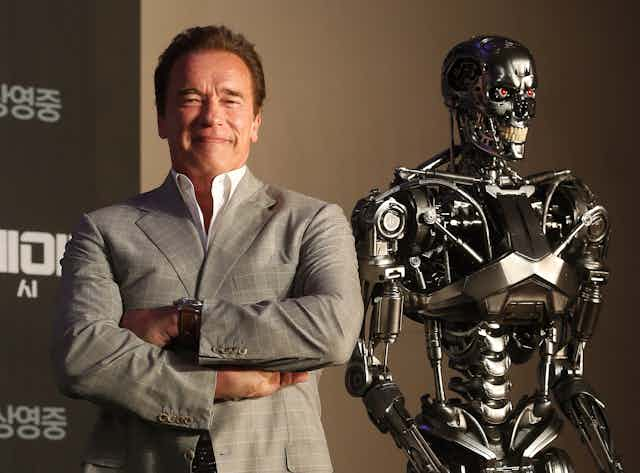

It’s been just over three decades since The Terminator (1984), wherein Arnold Schwarzenegger first declared “I’ll be back”. In the latest chapter in the franchise, Terminator: Genisys (2015), he continues to make good on his promise. He’s back (again) – and he has a new catchphrase: “I’m old, not obsolete.” Not his most menacing one-liner, is it? Even Bill Shorten could do better! Doesn’t it sound a little pathetic, even laughable?

But laughable, ridiculous one-liners have always been part of Schwarzenegger’s Hollywood career. He came to prominence as a prolific world champion in bodybuilding. His impressive physique was his ticket to stardom.

It landed him his first big role as Conan the Barbarian in 1982 and then as the Terminator two years later. Schwarzenegger was one of several muscle-bound action stars to emerge in the 1980s. The dominant physical profile of the action hero – tall, slim figures of grizzled masculinity such as Clint Eastwood or John Wayne – gave way in the 80s and early 90s to a more muscular frame.

Film scholar Susan Jeffords – in her 1994 book Hard Bodies: Hollywood Masculinity in the Reagan Era – links the emergence of these “hard bodies” to the socio-cultural climate of the time. The Reagan presidency, American ascendancy in the wake of the crumbling USSR, the reputed weakness of the previous Carter administration and popular obsession with fitness all contributed to Hollywood heroes transitioning into big, muscular metaphors for a reinvigorated United States.

While his bodybuilder’s physique was important for embodying larger than life, “All-American” action heroes, what made Schwarzenegger distinctive was his peculiar vocal performances in those roles. American action films often employ the wisecrack, the one-liner, or the pun after dispatching an enemy in a particularly creative way. But the vocalisations are invariably performed with an American accent, delivered with the confidence and fidelity of a native English speaker.

Where do we place Schwarzenegger in this tradition? Film and Women’s Studies scholar Chris Holmlund – in her book Impossible Bodies: Femininity and Masculinity at the Movies (2002) – suggests Arnie’s accent ensures a perception of “foreign ethnicity” that “is a plus in a country where, for the first time since 1930, one in ten people is now foreign born”. But one wonders whether this can fully account for Schwarzenegger’s mass appeal, particularly outside of the United States.

His heavily-accented delivery of snappy, pun-filled dialogue is often not quite right, just a little askew. The cadence or the inflection is frequently off. This, coupled with his generally low register, constantly reminds us we are watching Schwarzenegger rather than the character he is supposed to be playing.

This paradoxical demand to be the quintessential American hero while sounding “less American” than any of the other contenders is part of what endears him to his fans. It’s a sort of unintentional subversion of the Hollywood action hero. This appreciation for that artificiality is especially evident on the internet, where Arnold’s cumbersome vocal performances can be enjoyed with a kind of camp appreciation.

To be clear, camp, first popularised in Susan Sontag’s essay Notes on Camp (1964), is a term that suggests an ironic devotion to heightened, over-the-top style or artificial emotion – cultural product that is just “too much” or excessive, not measured or austere or subtle.

It has historically been associated with pop cultural icons adored by gay men (think Judy Garland), but the internet has enabled camp to become a far more common way of approaching culture. Many memes, quizzes, listicles, and “content” encourage an ironic perspective on celebrity and pop culture that’s awfully close to camp. Perhaps because of the association with homosexuality, camp has rarely been applied to action film, a notoriously heteronormative genre. But Schwarzenegger’s films tick all the boxes: over-the-top, heightened and artificial emotion, “style” over substance. So it’s no wonder this sensibility carries over into fandoms online.

Online fan activities that engage with Schwarzenegger’s vocal performances can be grouped into two broad tendencies: imitation and reiteration. Imitation is obvious enough. People on YouTube, and other platforms that allow recording, produce their impersonations of Arnold. There are even tutorials on “how to do Arnold”:

Reiteration is where most of my research has been focused, and includes video montages of Schwarzenegger’s greatest quotes as well as soundboard pranks. These are prank calls that are made using a selection of voice clips recorded from movies onto what is known as a soundboard, which the prankster uses to interact with a victim on the other end of the phone line.

These soundboard pranks are accompanied by a montage of images from Schwarzenegger’s films and other media stills, usually with him pulling an amusing facial expression or looking ridiculous:

Much of the “comedy” of these pranks derives from taking Schwarzenegger’s dialogue out of its cinematic context and re-purposing it to bizarre ends. These pranksters find a kind of nefarious joy in subjecting people on the other side of the phone to the strange directions Arnold’s recorded responses can take the conversation.

Another practice that can produce strange results is the phenomenon of Arnold-themed Twitter accounts. One of the most interesting was an automated tweet bot from a few years ago that scanned all of Twitter for account names that began with or included “Sarah Conner” or some similar variation.

The entire Twitter feed of this account was the bot simply asking every one of these accounts “Sarah Conner?”, referencing the first Terminator film where Schwarzenegger’s character goes to the house of every Sarah Conner in the phonebook and executes each woman after asking for them by name.

In his book Texual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture (1992), American media scholar Henry Jenkins described this kind of behaviour as"textual poaching.“ Fans appropriate aspects of their favoured texts and will redeploy them in various interesting ways. Arnold Schwarzenegger’s online fans have his prolific filmography to play with, but seem especially preoccupied with textually poaching aspects of his vocal performance.

This would seem to suggest that for most fans of Arnie, and despite much commentary focused on his "hard body,” his voice is paramount. For many of his fans, it doesn’t seem to matter how old and obsolete his once fantastic body becomes. He’ll be appreciated and celebrated as long as he can say things like “I’ll be back,” or my personal favourite, from Commando (1985):

I eat Green Berets for breakfast and right now I’m VERY hungry.