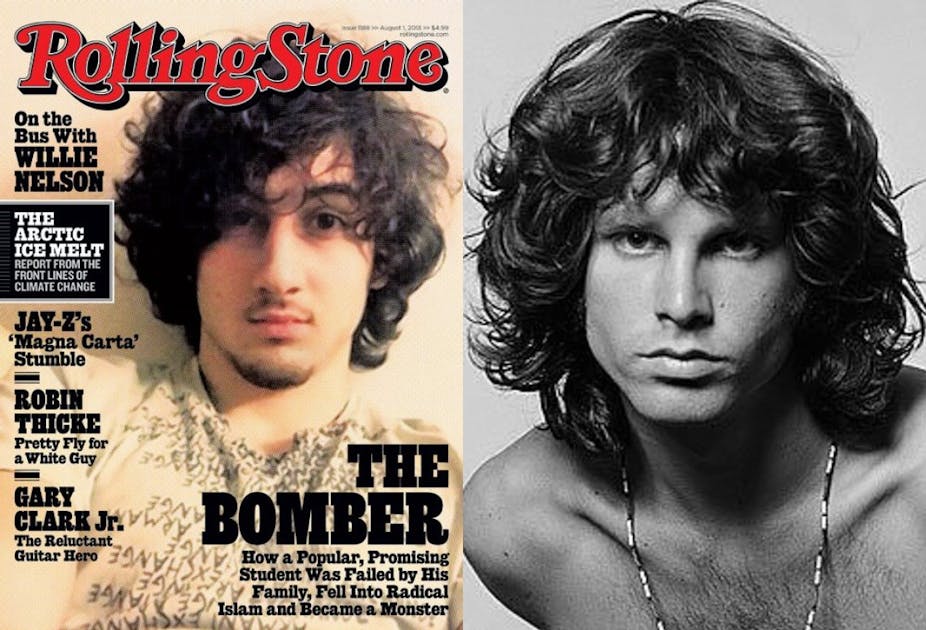

Popular culture magazine Rolling Stone has released the cover of its August 1 print edition on the internet. Most of the headlines promise the familiar mix of pop culture and news: a review of Jay-Z’s album, a thesis on why Robin Thicke appeals as an R&B artist, a tribute to the touring resilience of Willie Nelson, something on climate change. Then, straddling both worlds, we have Dzhokhar Tsarnaev.

Tsarnaev, the surviving suspect of April’s Boston Marathon bombings, is the front cover. The headline reads:

The Bomber: How a Popular, Promising Student Was Failed by His Family, Fell Into Radical Islam and Became a Monster.

It promises an important reflection on a significant global phenomenon. In the UK, following Lee Rigby’s murder, calls have been made for more research on the connections between the process of radicalisation and terrorism.

Of course Rolling Stone covers being what they are, the words are the last thing that catch your attention. As news websites pointed out, the cover prompted instant social media outrage by making Tsarnaev look like a rock star. Incensed readers pointed to the similarities between this picture and the classic Jim Morrison cover. That image of The Doors’ mythic frontman was instrumental in defining the rockstar photograph as a genre in itself. Understandably, many are outraged by the elevation of the alleged bomber to celebrity status.

It’s tempting to think that the magazine deserves the flak, as it clearly anticipated controversy. The editors have published a statement emphasising their sympathy for the Boston bombers’ victims, and defend both cover and story as being consistent with Rolling Stone’s “long-standing commitment to serious and thoughtful coverage of the most important political and cultural issues of our day”. Apparently, the cover emphasises that Tsarnaev looks like any ordinary young person. The intention is to create a deliberate juxtaposition: how can an handsome, talented, popular kid end up being implicated in such a willful atrocity?

But readers aren’t buying it. Literally.

Online readers have found different reasons to object. There’s reasonable, visceral anger at the glamourisation of a figure who is accused of maiming and murdering. But there are also accusations that Rolling Stone is jamming a square peg into a round hole. A reader called “Tom Russo” observed that the magazine brand depends on covers that “are traditionally seen as aspirational”, and it’s disingenuous to distance this cover from the rest.

We are accustomed to Rolling Stone covers being about sexy folks we want to be. They know it. We know it. No accompanying story or editorial comment can change that. Good journalism is arguably more important than it has ever been, while industrial changes make good journalists an endangered species. Clearly, Rolling Stone’s decision reflects commercial interests. Its ethical defence will doubtless be a matter of conjecture for some time, because it speaks to a growing public scepticism toward a media form that is integral to the health of society. This cause célèbre is a big deal.

Academic media research can’t answer the question “should this have happened”? But it can offer insights on why it happened, with its work on the connections between news and entertainment.

For a long time now, American magazines have sold themselves by attracting attention to horrible stories by using beautiful pictures. Back in the 1950s, “true life confession” magazines became enormously popular with American women. These titles typically told “true” stories about “good” girls who ended up in horrible situations. The victims of these narratives were always young women who wouldn’t go out with nice boys, or settle down to get married. One tale features a woman who takes the daring step of going on a European vacation, only to be seduced by an evil Austrian Nazi.

Researching these stories, social scientist George Gerbner noticed an intriguing anomaly: the covers of the magazines never reflected their content. Where the written copy outlined horribly lurid details of violence and degradation, the covers always featured its victims as sweet, beautiful and happy. The reason was simple enough: store owners wouldn’t stock covers featuring abuse. They worried that “true” covers would disturb customers’ buying mood.

The connection here is that there is a long history of writers having to ply their trade within the strictures of commercial media genres. So, a Rolling Stone cover story has to look like a Rolling Stone cover story. The magazine might have got it horribly wrong here, but this does prompt us to think about the relationship between news and entertainment.

Gerbner thought that entertainment creates powerful images about what the real world is like. Further, when we try to make sense of events of which we have no direct experience, we often fall back on familiar media narratives. Faced with incomprehensible horrors, one reaction is to interpret them through the genres that have become common vernacular. As Australian cultural studies professor Graeme Turner has argued, “celebrity” is one such language.

People are rightly asking if the cover is ethical. But a better way to get at the anger beneath this question is to ask if it was predictable, given the commercial pressures of competitive media markets.