Given the often hysterical media coverage of the refugee debate you could be forgiven for thinking that people seeking refuge in other countries is a new phenomenon. Not so. Refugees have been around since medieval times and we’d do well to learn from their stories.

Certainly the formal legal category of “refugee” is a product of the twentieth century, but they existed well before then. The very word “refugee” derives from the Latin term meaning “to flee” (fugere) and was first used in late sixteenth-century France to describe foreigners escaping persecution and in need of assistance (les refugiés).

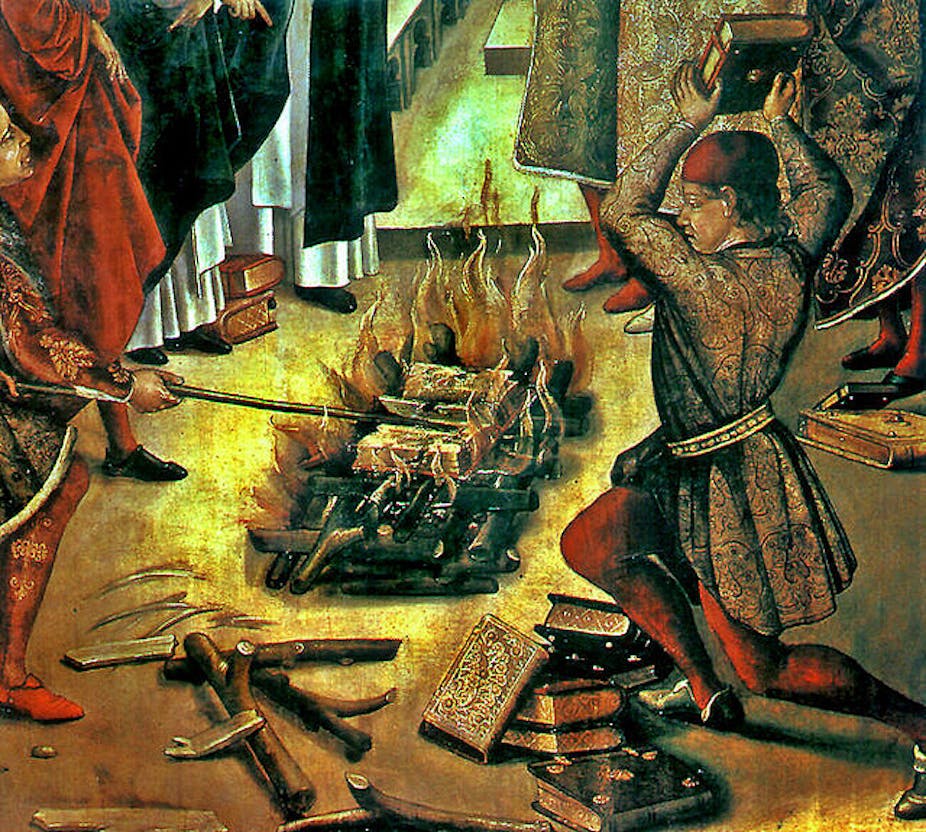

Even earlier than that, groups of people we would now call “refugees” can be found in the historical record. Camps full of displaced Visigoths grew up around the fringes of the crumbling Roman empire; the Crusades, both in the Middle East and in Europe, left populations displaced and unable to return home; the persecution of medieval Jews led to forced diaspora, especially from England, France and Spain. There are many other examples.

Lessons from the past

The presence of refugees in the past offers us a chance to see how experiences of displacement, fear, flight and exile are common to people across time and space.

Refugees from the crusade against heretics in thirteenth-century France, for instance, left behind records which document their attachments to family, community and location, and their despair and fear when armies forced them to flee homes they had occupied for generations.

French Jews of the late fourteenth-century who fled persecution to Italy wrote poignant poems of lament in which they tried to retain their previous identities as Frenchmen and women.

Such examples also tell us something about how “host” communities have dealt with new arrivals, both migrant and refugee.

Tolerance and persecution

Sometimes, surprising examples of tolerance can be discovered in these premodern records. In thirteenth-century France, refugees who were wrongly dispossessed of their property and assets as a result of their displacement were compensated.

These refugees became part of a longer national story of heroic self-determination in this region. The south of France now sells itself as “Cathar country”, a place where thirteenth-century refugee heretics are said to have bravely fought against the encroaching French monarchy.

Sobering examples of discrimination can also be found, especially in the form of violence against foreign populations.

This was often the case in times of economic stress. The Fleming Clothworkers of London were attacked during the Poll Tax riots in 1381 in a massacre that shocked even Geoffrey Chaucer, a contemporary observer, who described the violence as sounding like a “fox hunt”.

Modern day empathy

Recent calls to humanise the refugee debate in Australia have emphasised the need for empathy and the need to listen to individual refugee stories. The SBS programme “Go Back to Where you Came From” introduced individual refugees and their families to Australian men and women with strong views about refugees and asylum seekers.

At the heart of this programme was the idea that if only people could meet refugees and listen to their stories, then perhaps they would be more compassionate, empathetic and understanding of the situations which lead people to flee their homes.

Almost at the same time, former Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser argued in his Australian Refugees Association Oration last month that the tone of political debate around refugee issues is impoverished, and appeals only to the “fearful and mean sides of our nature”.

Fraser accused politicians of arousing “fears of the unknown of people who come from a different background, a different history, a different culture and also a different religion”.

He also recognised that history must play a part in the conversation about refugees, citing both Australia’s bleak past in the form of the White Australia Policy, but also its obligation to observe the Refugee Convention, ratified by Menzies in 1954.

Fraser’s recommendations were numerous, but were encapsulated by his call for a “humane and compassionate” response to people in distress and a policy shift towards humanitarianism rather than punishment.

Linking history to modern times

Premodern examples of refugees do more than provide interesting analogies to modern refugee experiences. They remind us that it is people who are at the heart of the historical record and that to understand them, we must listen carefully to their stories.

History does not just tell us what happens: it tells us how to listen. It is this humanising capacity of history that may link the distant past with current debate.

If the tone of the refugee debate in Australia is to become less fearful and more compassionate, then perhaps an exercise in empathy – an understanding of history – is a good place to begin.