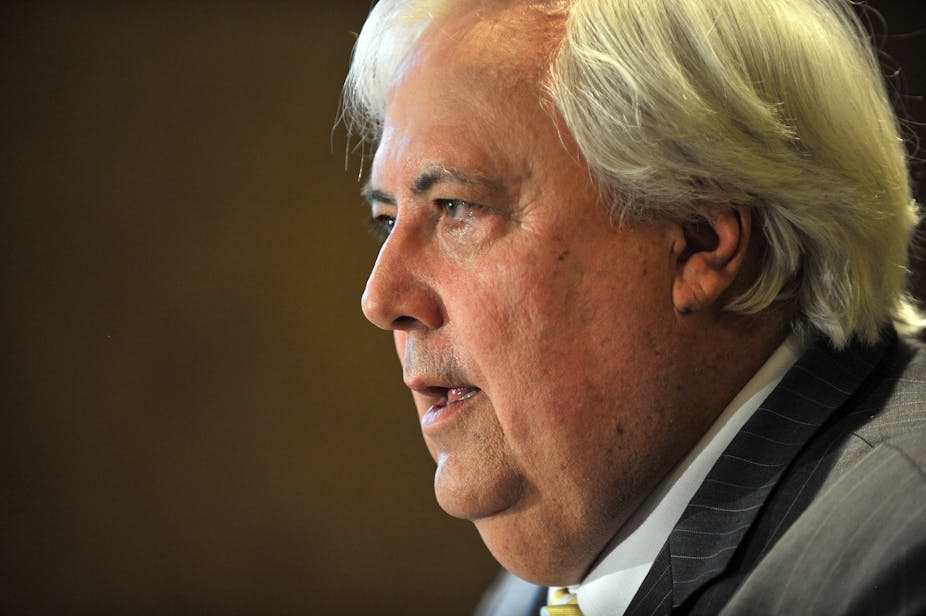

If you believe the recent media reports about the composition of the Senate from July 1 next year, you’d think we were facing three years of the Clive Palmer’s Palmer United Party (PUP) “bloc” holding the Abbott government to ransom.

But there are two important reasons to view such reports with scepticism.

The first is history. The last two parliaments have seen minority government, first in the Senate and then more recently the House of Representatives. Despite public fears of chaos and parliamentary dysfunction, reviews of these parliaments show that they have been very much “business as usual” – both in terms of legislative outputs and the limited direct influence of non-government members.

The second is the nature of the Senate. The metaphor that best describes my impression of the “balance of power” in that place is a game of Twister: every time someone looks up, everyone else’s position has changed - with the only constant being the rules of the game. You cannot count on numbers until after the vote is taken.

As senators of the PUP and Ricky Muir of the Australian Motoring Enthusiast Party (AMEP) will discover when they sit down for their inductions with the Senate Clerk sometime next year, the real power of the Senate is not in bold demands but in time and procedure.

So what are the Senate’s procedural options that can drive governments to distraction?

Beyond the well-known suspension of Standing Orders (which, even if unlikely to succeed, allows each senator to speak for five minutes to state their position), there are too many others to detail here. Let’s look at three.

First, the referral of bills to one (or multiple) committees for consideration is a common tactic to take up time. With the Senate’s brief as a house of review, this approach is often widely supported - even by crossbenchers that are likely to support government legislation.

Second, there are no limits on the sorts of information that the Senate can require a minister to produce. The option open to the Senate, should the minister refuse to produce the requested information, is that the refusal can be seen as contempt of the Senate and result in censure motions, halting the progress of particular bills or constraining the ability of ministers to handle government business.

Finally, when the number of bills logjam into the hundreds - and the government moves to circumvent usual procedure to see a bill handled in a day - it only takes the vote of one senator to stop such moves in their tracks.

Of course, the well-publicised version is the maverick senator(s) voting down government legislation. But in real terms, how great is this threat?

In reality, the pressure of being the last senator standing and the power of accusations of obstructionism are immense. The response of governments become incendiary and the attention of the media is laser-like, while the phones and email in parliamentary offices go into meltdown.

The shrewd senator adopts the shield of Senate procedure. This provides the opportunity to delay through “responsible review”, but also affords the option of voting down a bill at the second reading stage (if the government has not responded to senators’ requests). Neither strategy will contribute to a potential double dissolution trigger. Both put the pressure back on the government.

That said, the PUP bloc will face the usual practical challenges of all crossbenchers, including the need for additional staffing. However, there are also several specific issues that will require attention by the new PUP bloc.

One practical consideration is that most legislation will be introduced in the House of Representatives, not the Senate. This presents an interesting dilemma for the PUP bloc, as it will have to “play its hand” through Clive Palmer’s vote - provided he survives the recount in the lower house seat of Fairfax - before the main game takes off in the Senate. This will shift the attention to the remaining four senators, and while some have expressed conservative leanings, we don’t know how they’ll vote.

Another option for the PUP bloc is to leverage advantage by threatening to change its vote once a bill has reached the Senate, which leaves it open to criticism of backflips, opportunism and a lack of parliamentary integrity. This will be a difficult strategy to sustain under the constant scrutiny of the media.

It should also be remembered that if the PUP makes wild demands or struggles to master parliamentary procedures, its efforts will lose credibility and support from both of the major parties. There is a lesson to be learnt from the public decline of former senator Steve Fielding.

The “balance of power” in the Senate is the product of strict party voting discipline. A constant constraint that will be faced by the PUP bloc is that it will only be able to act on issues over which the major parties disagree - unless it opts for horse-trading.

During his recent Lateline interview, Palmer ruled out “bargaining things” with the Abbott government. This continues a long tradition of crossbenchers since (but not including) independent Senator Brian Harradine, who have been highly sensitive about attracting accusations of “horse-trading”.

In America, when two politicians promise to support each other on their pet issues they call it “logrolling”. The term comes from the 18th Century, when neighbours found it much easier to help one other move their logs than for each individual farmer to do it himself.

Of course, logrolling is part and parcel of the way political parties operate. Members of the ALP and Coalition, for example, agree behind closed doors on what they will or won’t support and then, having made such decisions, they vote as a bloc in the parliament.

When independent members of parliament (such as Ricky Muir) engage in deals as he has with the PUP - by necessity - they are far more visible. The question now for the Abbott government is: how strong is the deal between Palmer and Muir?

Abbott could try to divide Muir from his new-found allies by offering him more of his policy agenda than Palmer can, but if he does so, he runs two separate risks.

On the one hand, Abbott runs the electoral risk of appearing to put minority interests ahead of the national interest. On the other, he runs the parliamentary risk that clumsy attempts to woo Muir will simply drive him closer to the PUP.

Only time will tell if the PUP bloc can work better than they could as individuals, but given that their opponents will be desperate to divide and conquer them, it seems logical that the newcomers to the Senate will achieve more by rolling each other’s logs than they would trying to roll their own.

Meanwhile, the new Senate arrangements will continue to be surrounded by calls for reform. But when our forebears designed the procedures of the Senate, they had stability and democracy in mind.

Thankfully, these same principles are what will protect us from some of the bolder predictions about the future Senate aired in recent days.

Brenton Prosser is the co-author of ‘After “Independents’ Day” – have the independents made any difference?‘, a review of the 43rd Parliament in the book 'The Gillard Government’ to be published later this year by Melbourne University Press.