In early 2004, I downloaded The Grey Album, created by a then unknown producer named Brian Burton (aka Danger Mouse). Like many others I did so as a result of the Grey Tuesday protests sponsored by cyber liberties group Downhill Battle.

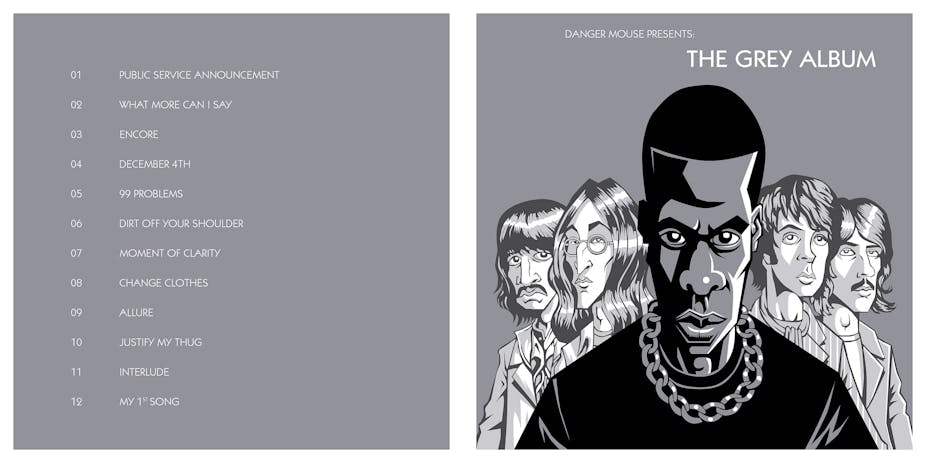

The protests saw hundreds of websites go grey to protest the cease and desist letters sent to Burton and his distributors by lawyers for Capitol Records. The album was a mash-up of Jay-Z’s The Black Album with rearranged, unauthorised samples from The Beatles’ so-called “White Album”. It briefly became a lighting rod for a debate that struck at the legitimacy of a long-recognised and valued form of artistic creativity: the interpretation of the work of one artist by another.

Ten years ago, it seemed to many that works such as The Grey Album were fighting the good fight for a free and open internet.

Ten years later, it’s hard to imagine the events of Grey Tuesday being repeated. “Free” music is ubiquitous and the long-standing practices of producers and remixers are seen for what they are: equal parts artistry, technique and publicity.

But while the landscape for digital music has changed dramatically, it hasn’t necessarily changed in the ways many people once thought it would. The fight for an open internet into which The Grey Album was drafted, has shifted to equally important, but far less emotive issues.

We have become heirs to what ANU academic Peter Drahos has called “the quiet accretion of restrictions”, the result of a debate that has receded behind what he aptly describes as a wall of:

technical rule-making, mystifying legal doctrine and complex bureaucracies, all papered over by seemingly plausible appeals to the rights of inventors and authors.

Music fans have been converted, according to cyber liberties scholar Patrick Burkart, into “music ‘users’ who lack property rights to their recordings and even rights to ordinary consumer protections”. These debates appear set for a long grind and, at the moment, do not promise anything like an egalitarian ideal of internet access or use.

Remarkably, there was one crucial thing at the heart of The Grey Album controversy that was never really addressed: the music. Specifically, few seemed to think that the aesthetic tradition of which this album is a part mattered to the debate over its legitimacy. But there is little question that it matters more than anything else.

Much of the commentary about The Grey Album in particular and mash-ups in general linked these musical forms rather lazily to the big idea of the early 21st century: newness. We were told by a whole range of digital “visionaries” and hangers-on that we were suddenly in the throes of a new world and this new world had to have a new art, a new commerce and a new media.

A lot of the writing about The Grey Album sought to transform it into a kind of rabblerousing street pamphlet for the digital age. It was nothing of the kind. The Grey Album was a crucial link between the past and the present. It still stands, not as some harbinger of our once inevitable future, but a link in a long chain of musical practice that stretches back to the late 1960s.

The aesthetic lineage that produced The Grey Album includes cornerstone forms such as dub, hip-hop and electronic dance music. It is drawn from the long, rich history of the musical manipulation of recorded sound in hip-hop and a multitude of different forms of electronic dance music.

This is a musical tradition that has been practiced for decades through the use of recorded sound as the grist for the seemingly endless configuration, amalgamation and juxtaposition of myriad samples, loops and drops of familiar and unfamiliar music. This complex and expansive musical lineage has had an enormous influence all over the world.

Yet many of its practitioners have long been subjected to damaging campaigns of legal and economic harassment not only over the legitimacy of their music, but over the tools, techniques and materials they have used to make it. And it is in specific relation to these fights over the use and reuse of existing musical materials that The Grey Album is particularly important.

It presented us with musical practices, emergent at the time and taken for granted today, that make it an important marker of the intense and persistent struggles over the production, distribution and consumption of popular music.

None of the skills Danger Mouse brought to bear on this album were new. He listened to his source materials in ways DJs had for decades. He dismantled and reconstructed his sources in ways that would have been at least somewhat familiar to musical practitioners going back decades.

The Grey Album represented a collision between the supporters of that tradition and outsiders who simply had no real understanding of what they were dealing with. Most importantly, it was the widespread recognition of Danger Mouse’s skill and his mastery of his tradition that made his supporters shape their resentment into the blunt and largely successful force of civil disobedience.

The aesthetic legitimacy of The Grey Album, as with other works in this musical tradition, does not depend on how clever its producer is or how faultless the manipulation he enacted on his source materials might have been. Nor does it depend on how artistically successful it might be. Its aesthetic legitimacy depends on it being recognised and accepted as a part of an identifiable and living tradition of artistic practice.

The sooner those with an interest in the law, technology and music take an interest in this the better.

Danger Mouse’s The Grey Album by Charles Fairchild is published by Bloomsbury.