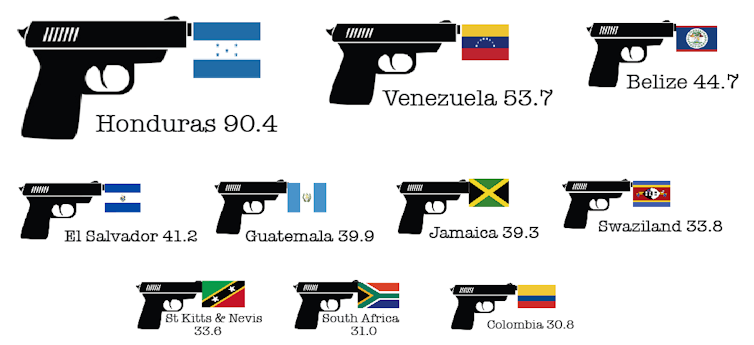

On November 19, the bodies of sisters Maria Jose and Sofia Alvarado were found dumped in a grave outside the provincial town of Santa Barbara in western Honduras. In a country that has the highest murder rate in the world – in 2012, it registered 90.4 murders per 100 000 population, more than twice that of neighbouring El Salvador and Guatemala – most victims are poor and nameless.

Crimes are rarely investigated in any meaningful way and it is normal for the perpetrators to get away with it. Corruption is widespread and security forces have been implicated in significant numbers of violent murders.

The killing of the Alvarado sisters caused a stir only because Maria Jose was the reigning Miss Honduras and due to represent her country at the Miss World competition in London. Otherwise the murders would like have become just one more statistic, dismissed as the result of a jealous lover or possessive partner.

Highest murder rates per 100,000 people, 2012

Machista culture

The causes of violence in Honduras are complex. In the 1990s and 2000s, youth gangs dominated the media and policy agendas. Less attention was given to high levels of violence against women and LGBT groups, against whom violence was often normalised as part of a machista culture and tended to be ignored. Most analyses of this new wave of violence agreed that it was social in nature and the responsibility of emerging criminal groups. Less attention has been given to state and wider citizen involvement.

In response to rising crime levels, the government pursued a series of repressive policies throughout the 2000s, known as “mano dura” (iron fist). These increased the coercive powers of the police and military in waves of repression that largely targeted poor urban youth.

The policy enjoyed the support of a majority of Honduran citizens, yet the effects have been largely counterproductive: mass arrests, a huge increase in the prison population, a greater institutionalisation of gangs and the space for other criminal organisations to consolidate a significant presence in the country.

Cops and coups

Honduras, like other parts of Central America, is in the direct transport route for narcotics moving northwards, which foments both violence and corruption. Local narco influences either take advantage of weak state capacity or simply transplant state authority in a given locality. Increasing areas of Honduran territory are under the control of narco interests, while an estimated 50% of the Honduran police force have been corrupted by drug gangs. Trust in the institution is among the lowest in the region.

These police shortcomings have deeply political roots. In 2009 the elected president Manuel Zelaya was removed from office by the military and sent to neighbouring Costa Rica (still in his pyjamas). While the coup did not cause the high murder rates in Honduras, two issues make it relevant.

First, it exposed the subservience of state institutions to the political and economic interests of the elite who had Zelaya removed. The move was deemed wholly constitutional by both the supreme court and the legislature despite its widespread condemnation by domestic and international actors, including US President Obama.

Second and more pertinently here, the coup and its aftermath unleashed a wave of political violence that targeted a range of activists, including journalists and human rights defenders. UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) figures show that after the coup the murder rate increased from 60.8 per 100,000 in 2008 to 81.8 in 2010, 91.4 in 2011 and 90.4 in 2012.

Violence begets violence

Political elites used the existing context of insecurity to attribute much of this violence to common crime, while conservative pro-coup groups unleashed a targeted campaign of violence against women and LGBT groups. Most of the ensuing murders have not been investigated.

Illicit groups such as criminal gangs and drug cartels took advantage of the wider context of impunity to consolidate their position in the country. Wealthy business groups who pursue profit with little regard for the human costs have meanwhile consolidated channels of corruption. For example in one northern region, the Bajo Aguan, more than 140 peasants have been killed since 2009 in conflicts over land tenure after they were evicted to make way for massive African palm-oil plantations. At stake is fertile land and massive profits.

Witness statements claim that they have been killed by private militia forces, which operate with the tacit consent of government forces. Many of those who work for these private companies are off-duty military or fall under their protection, thus not only blurring the lines between public and private agents but also guaranteeing themselves impunity for their crimes.

Impunity is a problem within Honduras, not just because justice is refused to individual victims of violence, but also because it creates a context where certain groups exist above the rule of law. Violence against certain groups is rationalised and even welcomed. Impunity and repression undermine the rule of law at every level and thus the cycle perpetuates itself. The murders of the Alvarado sisters are part of a far bigger problem that is showing no signs of coming under control.