While Christmas playlists often include cheesy favorites like “Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree” and “I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus,” there are also a handful of wistful tracks that go a little bit deeper.

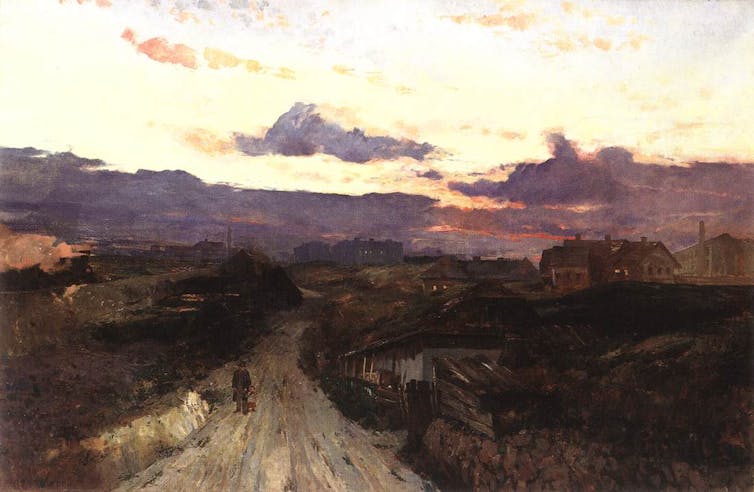

Listen closely to “I’ll Be Home for Christmas” or “White Christmas,” and you’ll hear a deep yearning for home and sorrow at having to spend the holidays somewhere else.

During no holiday season in recent memory have these songs resonated so deeply with so many. The pandemic has upended holiday traditions, and for those who eagerly anticipate annual visits to their hometowns to celebrate with loved ones, the cancellations of these plans are yet another blow to endure in a long, grinding year.

Strip away the cursory Christmas rituals – the TV specials, the lights, the gifts, the music – and what remains is home. It is the beating heart of the holiday, and its importance reflects our primal need to have a meaningful relationship with a setting – a place that transcends the boundary between the self and the physical world.

Can you love a place like a person?

Most of us can probably name at least one place we feel an emotional connection to. But you probably don’t realize just how much a place can influence your sense of who you are, or how essential it is for your psychological well-being.

Psychologists even possess an entire vocabulary for the affectionate bonds between people and places: There’s “topophilia,” “rootedness” and “attachment to place,” which are all used to describe the feelings of comfort and security that bind us to a place.

Your fondness for a place – whether it’s the house where you lived your whole life, or the fields and woods where you played as a child – can even mimic the affection you feel for other people.

Studies have shown that a forced relocation can elicit heartbreak and distress every bit as intense as the loss of a loved one. Another study found that if you feel a strong attachment to your town or city, you’ll be more satisfied with your house and you’ll also be less anxious about your future.

Our physical surroundings play an important role in creating meaning and organization in our lives; much of how we view our lives and what we have become depends on where we’ve lived, and the experiences we’ve had there.

So it’s no surprise that architecture professor Kim Dovey, who has studied the concept of home and the experience of homelessness, confirmed that where we live is closely tied to our sense of who we are.

An anchor of order and comfort

At the same time, the concept of home can be slippery.

One of the first questions we ask when we meet someone new is “Where are you from?” But we seldom pause to consider how complicated that question is. Does it mean where you currently live? Where you were born? Where you grew up?

Environmental psychologists have long understood that the word “home” clearly connotes more than just a house. It encompasses people, places, objects and memories.

So what or where, exactly, do people consider “home”?

A 2008 Pew study asked people to identify “the place in your heart you consider to be home.” Twenty-six percent reported that home was where they were born or raised; only 22% said that it was where they currently lived. Eighteen percent identified home as the place that they had lived the longest, and 15% felt that it was where most of their extended family had come from.

But if you look at different cultures across time, a common thread emerges.

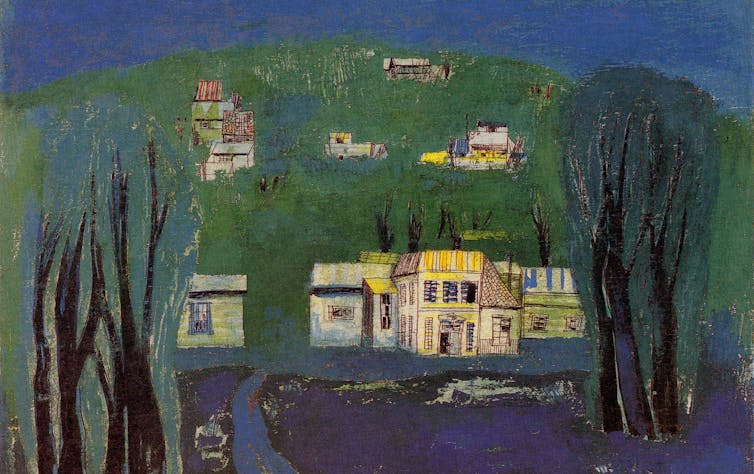

No matter where they come from, people tend to think about home as a central place that represents order, a counterbalance to the chaos that exists elsewhere. This might explain why, when asked to draw a picture of “where you live,” children and adolescents around the world invariably place their house in the center of the sheet of paper. In short, it’s what everything else revolves around.

Anthropologists Charles Hart and Arnold Pilling lived among the the Tiwi People of Bathurst Island off the coast of Northern Australia during the 1920s. They noted that the Tiwi thought their island was the only habitable place in the world; to them, everywhere else was the “land of the dead.”

The Zuni of the American Southwest, meanwhile, have long viewed the house as a living thing. It’s where they raise their kids and communicate with spirits, and there’s an annual ritual – called the Shalako – in which homes are blessed and consecrated as part of the year-end winter solstice celebration.

The ceremony strengthens bonds to the community, to the family – including dead ancestors – and to the spirits and gods by dramatizing the connection each party has to the home.

During the holidays, we might not officially bless our home like the Zuni. But our holiday traditions probably sound familiar: eating with family, exchanging gifts, catching up with old friends and visiting old haunts. These homecoming rituals affirm and renew a person’s place in the family and often are a key way to strengthen the family’s social fabric.

Home, therefore, is a predictable and secure place where you feel in control and properly oriented in space and time; it is a bridge between your past and your present, an enduring tether to your family and friends.

It is a place where, as the poet Robert Frost aptly wrote, “When you have to go there, they have to take you in.”

This is an updated version of an article published on Dec. 13, 2017.