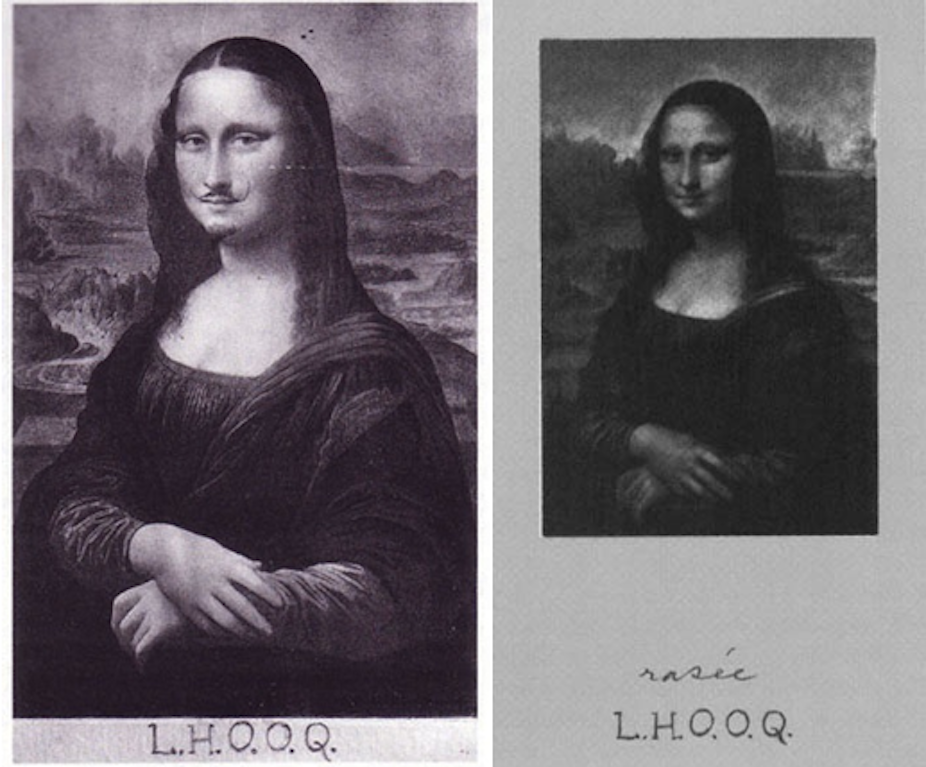

Can you spot the difference between these two images? They are both by French conceptual artist Marcel Duchamp. On the left is L.H.O.O.Q. (1919) where Duchamp drew a moustache and beard on the picture of Mona Lisa. You may wonder about the acronym he chose as a title for this. If you pronounce the letters in French, what you get sounds like “Elle a chaud au cul” (my humble translation: “She’s horny”).

On the right is L.H.O.O.Q. rasée (where “rasée’” means “shaven”), a piece Duchamps did much later, in 1965. It is a reference to the earlier picture – but it is perceptually indistinguishable from a faithful reproduction of Leonardo’s Mona Lisa. But, having seen his moustachioed Mona Lisa, it is very difficult not to see differently from the way we see Leonardo’s original. Give it a try. Here’s the original just to refresh your memory:

The missing moustache and beard is very much part of our experience of L.H.O.O. Q. rasée – whereas it is not when we look at Leonardo’s original. And it is difficult to see how we can describe our experience of L.H.O.O.Q. rasée without some reference to the mental imagery of the missing beard and moustache.

Perception versus ideas

The standard story of the art of the 20th century is that artists have gradually turned away from perception and towards concepts. Contemporary art, according to this line of thinking, is not about how things look, but about our ideas. But this is not a convincing story.

Contemporary art is as much about perception as the art of the mid-20th century. But it is about a very specific perceptual phenomenon: mental imagery. If we look at some of the most iconic conceptual artworks, it is easy to see that they are not trying to get you to think complex thoughts. They are trying to trigger a specific kind of mental imagery. That is clearly the whole point of L.H.O.O.Q. rasée. But there are many other examples.

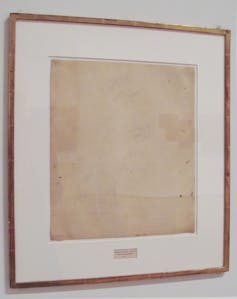

Here is another famous one: Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning drawing (1953), which is just what it says it is: all we see is an empty paper (with hardly visible traces of the erased drawing on it).

A little background: Willem de Kooning was one of the most influential painters working in New York when the young and not particularly respectful Rauschenberg asked him for a drawing telling him straight up what he was going to do with it. De Kooning did not want to make Rauschenberg’s job easier, so he used all kinds of different techniques (pastels, pencils, crayon, charcoal, even ink) to make the erasing less easy.

When you look at the Erased de Kooning drawing, it is difficult not to try to discern what drawing might have been there before Rauschenberg erased it. And this involves trying to conjure up mental imagery of the original drawing.

More to the image

Duchamp and Rauschenberg are classic examples of how artists can exploit what you know – or what you think you know – to make you see art differently. But there are many more. Here is just one more: Ai Wei Wei’s monumental installation, Straight (2013). That’s the way it looks.

What you can’t tell by looking is that the 150 tons of steel rods used for this installation are in fact, the rebar from the reinforced concrete school buildings that collapsed in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, killing many students. Ai Wei Wei collected the steel rods and straightened them for this installation piece.

If you know where these pieces of metal came from, your experience of the artwork changes significantly. It is difficult not to imagine how these bars were poking out of the rumble of mountains of concrete burying many schoolchildren underneath. If you look at the installation without knowing about the origins of the bars and then later, after reading about the earthquake, you look at it again, your experience will be very different. And this difference is mainly due to the difference in mental imagery.

Really seeing

All these artworks show how mental imagery can completely transform our experience. Here is a story the French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson liked to tell: during the war, he was hiding in a shed in the middle of the nondescript German countryside surrounded by a mountain range for weeks. Then one day he visualised the ocean behind the mountain range. And this completely transformed his experience (in a positive way). Not only his experience of the mountain range, but also of his general situation and of himself. Mental imagery does have a huge influence on the way we perceive and on our mental life in general.

Susan Sontag was trying to provoke when she wrote, more than 50 years ago, that: “The basic unit for contemporary art is not the idea, but the analysis of and extension of sensations.” But the past 50 years have suggested that she was right and we now have a pretty good grip on this “extension of sensation” she talks about: it is about exercising mental imagery.