This article contains spoilers for the Game of Thrones TV series and the books upon which it is based.

Ask people what they know about witches and the most common response is that they were burned alive during witch trials in early modern Europe and America.

But if you’re an avid fan of the HBO television series Game of Thrones (2011-), chances are you know more about witches, medieval Christianity and early modern religious iconography than you think.

George RR Martin – author of the books on which Games of Thrones is based – has openly drawn on medieval and early modern history and religion in crafting his world.

Yet just as interesting as his engagement with religious themes and ideas is his playful subversion of them – particularly when it comes to his depictions of witchcraft.

In Season 1, the Lhazereen “godswife” Mirri Maz Duur embodied all the key aspects of the witch trope: she was deceitful, vengeful and met a fiery death. When the Red Priestess Melisandre was introduced in Season 2, the series’ use of witch tropes became more complex.

Like many of Game of Thrones’ powerful women, who both embody and subvert traditional representations of gender, Melisandre challenges our perceptions of witchcraft.

Melisandre: priestess or witch?

When she first appears, Melisandre burns statues of the Westerosi gods The Seven at Dragonstone. In the same scene, she becomes the Merlin to Stannis Baratheon’s King Arthur, encouraging him to pull a burning sword from a flaming statue. Through this alliance, her magical powers have been instrumental in destroying all five Kings who appeared in Season 2.

In fact, Melisandre is arguably the most powerful woman in Westeros. Across the series, her actions and influence alters the balance of power.

Though she is called the “red woman”, or a “priestess”, Melisandre’s religious practices blur the lines between the mystical and the magical – a line which early modern people often understood as the divide between the Godly and the diabolic.

The Seven and R'hllor: Westeros’ God and Satan?

The official religion of Westeros is worship of The Seven: the Father, the Mother, the Maiden, the Warrior, the Smith, the Crone and the Stranger.

There are several strong parallels between The Seven and the Roman Catholic Church in medieval and early modern Europe.

It is essentially a monotheistic religion as The Seven are seven aspects of one deity, invoking the Holy Trinity. The Father correlates with God the Father while the Mother and the Maiden have Marian connotations.

Without making a simplistic comparison with the Devil, the motifs used to represent Melisandre’s god R’hllor, the Lord of Light – notably fire, magic and prophecy – have counterparts in medieval and early modern religious iconography.

Historian Stuart Clark argues in Thinking with Demons (1997) that witches were viewed by early modern people as practitioners of a Satanic religion, which inverted Christian social order. It was this heresy that caused the fiery executions of witches in many jurisdictions.

Like witches, R’hllor’s priests and priestesses are clearly viewed by servants of the Seven as a subversive threat to the religious conformity of Westeros.

Early modern witches were believed to be part of a religious inversion of Godly society. In Game of Thrones Melisandre is in many ways the early modern Christian’s nightmare made real. She has tangible magical power, political authority, and she is winning (at least early in the series) new converts to her cause.

Not the wicked witch

In Westeros, as in early modern Europe, not all witches resemble the Halloween stereotype of the old witch – an ancient crone covered in warts. Westerosi witches do, however, recall other stereotypes about the power of sex, blood and magic.

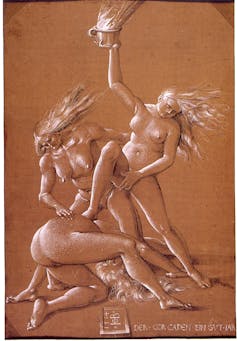

Medieval and early modern witches had many faces. Francesco Maria Guazzo’s Compendium Maleficarum (1608) contains images of men and women, young and old, participating in acts of Devil worship – such as The Obscene Kiss (1608).

Since one of the primary concerns about witches was that the lustful nature of women – especially young women – put them at a greater risk of being tempted into sin by the Devil, it is unsurprising that early demonological works took those fears a step further, into actual sex with the Devil.

The Malleus Maleficarum (1487), one of the most significant texts for the period of the great European witch-hunt, claimed that witches “persistently engage in the Devil’s filthy deeds through carnal acts with incubus and succubus demons”.

German printmaker Hans Baldung Grien’s 1514 drawing, alongside dramatic works, such as The Witch (c.1609-1616) and The Late Lancashire Witches (1634), depicted witches of all ages acting lewdly. In Thomas Middleton’s The Witch, one character declares:

What young man can we wish to pleasure us

But we enjoy him in an incubus?

Like these witches, Melisandre is highly sexualised. In only her second episode she encourages Stannis to “give himself to the Lord of Light” by sleeping with her, in betrayal of his marriage vows.

Bloody Rites

Melisandre also requires blood for her strongest magic, and this is the motivation behind many of her most atrocious acts (more on this below). Blood magic has a long pedigree in historical depictions of witches.

In early modern England, many witch trials depicted witch’s familiars demanding blood from witches. Bodily fluids such as blood and hair were also used by both cunning-folk (good witches) and malefic witches (bad witches, who committed acts of maleficium, or harmful magic).

In season 5, Game of Thrones introduced its third representation of a witch, Maggy the Frog. Maggy explicitly uses blood magic. But unlike Martin’s description in A Feast for Crows (2005) – ancient, warty, terrifying yellow eyes – the television adaptation morphs Maggy into a young, attractive woman.

When Maggy sucks the young Cersei Lannister’s blood, this recalls the familiars in English witch trials who suckled witches in return for acts of magic. It also recalls the way cunning-folk used urine for scrying, or telling the future.

Subverting our preconceptions

The depiction of witchcraft in Game of Thrones therefore engages with many historical witch tropes. But Melisandre is at her most powerful, and compelling as a character, when she subverts these tropes and becomes the facilitator of ritualistic burning.

R'hllor might not be an evil god, but his servants do terrible things in his name. The most striking is when Melisandre convinces King Stannis to let her burn his daughter Princess Shireen alive in exchange for a “miracle”.

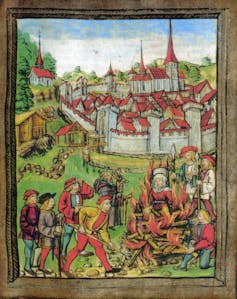

Melisandre also orders the burning of wildling leader Mance Rayder, as pictured in the main article image. Her authority is strong enough to order his execution despite strong opposition on several fronts.

The orchestration of these two deaths is the most dramatic demonstration of Martin’s subversion of the traditional “witch” role. Instead of practising her magic quietly for fear of persecution, like Maggy the Frog, she wields her magical abilities as an integral part of her religious and political power.

Melisandre, Mirri Maz Duur and Maggy the Frog embody familiar tropes about witches and witchcraft. But Melisandre also subverts and plays with our preconceptions of her role in this world – which is exactly what Game of Thrones does at its finest.