Women sharing their accounts of violence against them, and its aftermath, can be powerful. Feminism has long since taught us that personal experiences of violence, when shared collectively, can transcend the level of individual harms and form the basis for understanding the political significance of these accounts.

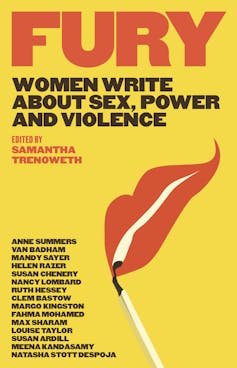

And, according to 16 “feisty and bold” women – in the book Fury: Women Write About Sex, Power and Violence (2015), edited by Samantha Trenoweth – we need fury. But more than mere rage, Trenoweth invokes the mythical furies of Greek mythology, to suggest that we need “avengers of murder, dispensers of justice” to challenge men’s violence against women.

Perhaps the personal experience of violence is an insight and an important form of knowledge that we’ve lost. Sure, we know the figures regularly cited to us from the Australian Institute of Criminology and the Australian Bureau of Statistics. Almost one woman a week will die as a result of violence from her male partner or ex-partner. One in five women experience sexual violence in their lifetime. One in three women will experience violence in their lifetime, most commonly at the hands of an intimate partner, ex-partner or other known man, and most often in a private home.

And while one in two men will experience violence in their lifetime, it is overwhelmingly at the hands of other men and in public space – sometimes, it is even thought to be the sign of a “top night out”.

Men’s violence against women, and against other men, is a significant problem. But somehow knowledge of the extent of the problem is not enough to promote widespread understanding and to stop it from happening.

The economic cost of men’s violence against women and the impacts on children and families is estimated in the billions – annually.

According to VicHealth, intimate partner violence is responsible for more preventable ill-health and premature death in Victorian women under the age of 45 than any other of the well-known risk factors, including high blood pressure, obesity and smoking.

Yet, according to the National Survey of Community Attitudes to Violence Against Women, many Australians continue to think that violence against women is not all that common, or that it is not a problem related to gender (after all, men can be victims too, and not all men…), or that surely women share the blame and responsibility for men’s violence: if they are unfaithful, for example, or were drinking alcohol, or say “no” which he takes to mean “yes” – basically if they exhibit signs of being regular, imperfect, human beings.

So what else can be done? What do we need to do to convince Australian society that not only is men’s violence against women a significant problem – but it is one for which we are all collectively responsible for ensuring that it is stops - now? That we all – women and men – need to work together to make sure that men’s violence against women no longer happens in our homes, our workplaces, our local communities?

Fury

In editing Fury, Trenoweth found her “literary furies” in women such as Van Badham, who writes a compelling narrative, a metafiction, that is archetypical of the everydayness, the confusion of feelings, the social shame and obligations, the messiness of a young woman struggling to comprehend her abusive boyfriend’s behaviour.

Mandy Sayer and Susan Chenery both relate personal and moving accounts of different experiences of violence in their lives.

Anne Summers reflects on the founding of Elsie, the first Australian women’s refuge, in 1974. Summers’ account is one of the practical needs and fearful realities of women fleeing violence, often accompanied by their children, and while there are now many more women’s refuges it is dismaying to note that the demand for this fundamental service still exceeds availability.

Meanwhile, Clem Bastow and Helen Razer call for a revolution. Nothing short of concerted political activism – the ongoing and unfinished project of feminist movements locally and globally – will stop men’s violence against women and the gender inequality that underpins it.

In sum, we already have awareness of the extent of the problem. The challenge is to do something – something radical – about it. We need to smash the system that allows men’s violence against women to continue.

Natasha Stott Despoja is perhaps less radical, but no less determined about what needs to be done. Ending violence against women will require societal change to challenge and end gender inequality at each and every level of our society.

That much is clear. How to do that? Continuing to keep the issue on the political and public policy agenda, challenging governments, the media, indeed all Australians to agitate for change?

Contributions by Louise Taylor highlight the particular experiences of Indigenous women, who are significantly more likely to experience family violence than non-indigenous women.

Meena Kandasamy writes of the efforts of Indian women to challenge rape culture, which was brought into sharp focus by the gang rape of a young woman in 2012. Fahma Mohamed and Lisa Zimmerman share their account of an activist project to stop female genital mutilation in the UK, highlighting its connection – through cultural legitimacy – to trends in mainstream UK, US and Australian societies, where rates of vaginaplasty, labiaplasty and vulvaplasty are increasing steadily.

If there’s a weakness of this book it might be that it is not an instruction manual for solving the problem. There are some strategies suggested for challenging the gendered inequalities that underlie violence against women. But you won’t find here specific directions for concrete actions and policies that Australian governments should develop or invest in, nor the on-the-ground programs and services that government and non-government agencies could deliver to more women, more children – and more men.

Mind you, we have seen plenty of those instruction manuals over the years. Research report, after policy recommendation, after program pilot and evaluation – some of which (in fairness to our political leaders) are subsequently developed, funded and delivered. But not enough to provide the core services women need to escape from violence in their homes – and not nearly enough to prevent the violence before it occurs.

What Fury does is meet another need. The accounts of violence, abuse and responding to its aftermath that are shared by the women writers here, remind us of something else vitally important that we ought not to forget.

Most of us are survivors of violence, or know someone who is. I am, and I do.

Too often we hide these personal experiences. Perhaps we feel our work whether it is in the service sector, or in government policy, or in academic research, or as a caring friend or family member, will be dismissed as biased, emotional – or feminist.

Yet we have every right to stand with survivors, to be emotional – even furious – and to work collectively towards a society in which women not only live free from violence, and the fear of violence, but are able to go about their lives autonomously as equals. These are the aims of a feminist movement against violence.

And to paraphrase Jill Filipovic (another “feisty and bold” woman writer and weekly columnist for The Guardian):

Sharing our experiences without anyone else’s approval or endorsement is what initially brought men’s violence against women out of the shadows. Continuing to speak the truth is what keeps the light on.

Fury – Women Write About Sex, Power and Violence, edited by Samantha Trenoweth, is published by Hardie Grant Books.